The first lines of Wilfred Owen’s poem ‘Insensibility’ (1893 – 1918) bear testament to the chilling impact of the First World War on those who participated in it:

Happy are men who yet before they are killed

Can let their veins run cold.

Whom no compassion fleers

Or makes their feet

Sore on the alleys cobbled with their brothers.

The sacrifice of more than 16 million lives on the altar of an unfeeling war machine and the traumatisation of millions more, which Owen, writer Jean Norton Cru and other like-minded eyewitnesses so evocatively captured, have become the point of reference for the modern remembrance of 1914-18. It is easy enough to understand why the horrors of the trenches, the introduction of ever more efficient methods of killing and atrocities like the Armenian genocide have left such an indelible impression on the collective imagination.

And yet societies’ adaptation to what the Dublin historian John Horne has termed the “totalitarian tendencies” of the Great War cannot be reduced to the corrosive effects of trauma alone. Rather than rendering combatants “insensible”, as Owen believed, the long duration of the war actually owed a great deal to citizens’ emotional mobilisation for higher ideals. While the choice of belligerent nations to frame their struggle in terms of a “last crusade” might be dismissed as a propagandistic tool to shame the enemy, the rhetoric of chivalry counteracted the inhumanity of the conflict in sometimes surprising ways.

Captivity and honour

Consider the 8 million soldiers who ended up in captivity during the course of the war. The capture of so many troops presented armies with serious challenges. Protocols of surrender were ill-defined and facilities for housing the men limited. Although prisoners consequently experienced abuse on a massive scale, the hopes of one German pre-war legal scholar, Paul Wünnenberg, that captives should regain their freedom as long as they gave their word of honour to henceforth accept only non-combat duties were realised in a selective fashion.

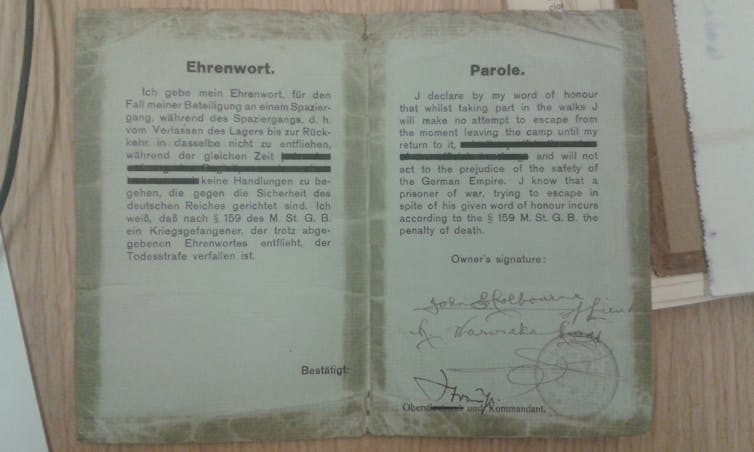

For instance, in September 1914 the French war ministry issued special instructions that allowed captured officers to keep their sword and to rent comfortable private accommodations in picturesque towns, where they could walk about if they consented in writing to abstain from escape attempts.

Avoiding the cost and inconvenience of having to employ guards, the British and German authorities early in the war likewise opted to release captured civilians and merchant crews once they had promised not to serve against the captor state. In at least one case, a British officer even gained temporary release from captivity to visit his dying mother after pledging his personal honour to return, which he did.

To be sure, even though international humanitarian law in the shape of the Hague Conventions (1899/1907) endorsed parole agreements, belligerents largely abandoned the custom in the first year of the war. In itself this development was perhaps not surprising, for parole agreements imposed a moral obligation on prisoners to eschew escape, which deprived governments of their service. Furthermore, the option to enter into contracts with the enemy injected a democratic element into warfare by empowering the individual soldier to decide for himself when to quit the fight.

Parole agreements

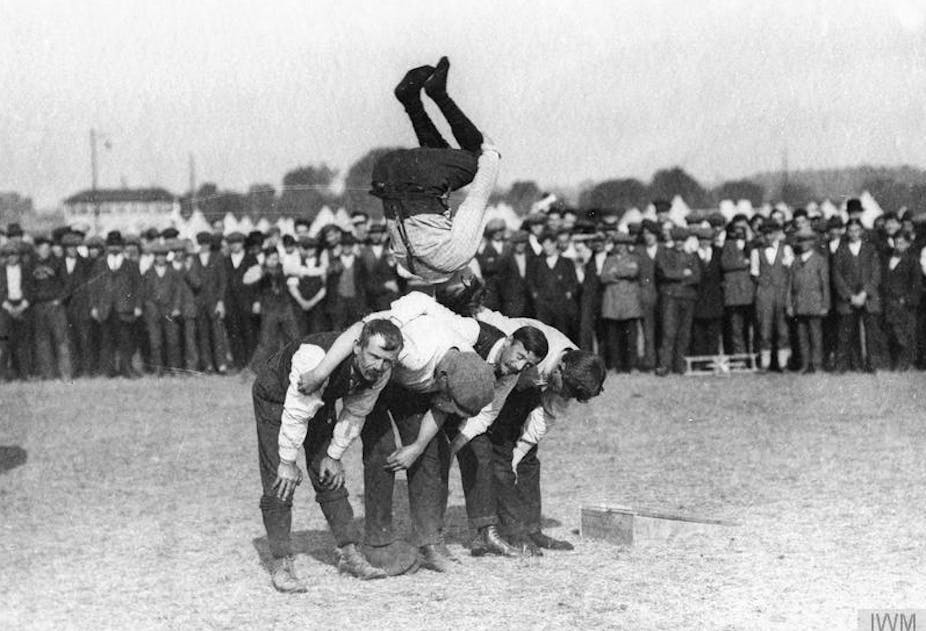

More remarkable was the return of parole agreements in modified form during the second half of the Great War. The proliferation of “barbed wire disease” among long-term prisoners led to a series of bilateral treaties between Britain, France and Germany that provided for the internment of sick captives in neutral Switzerland as well as the Netherlands. These agreements entitled internees to visit local towns in return for their word of honour not to escape. The option to take short walks outside the camp walls also became available to officers who remained behind in Germany and agreed to sign so-called parole cards.

The resurrection of parole as part of wider endeavours to improve captivity remind us that the cataclysm of the First World War was more than just a race to the bottom. Though too uncoordinated in the final resort to stem the systemic violence unleashed by the conflict’s “dynamic of destruction”, these philanthropic impulses held important lessons for the subsequent course of humanitarian thought and practice (as evidenced, for instance, by the new Geneva Convention of 1929).

The “sentiment d’honneur” was integral to this learning process because it constituted the primary guarantee for soldiers’ good conduct, as the Belgian international lawyer Gustave Rolin-Jacquemyns had pointed out as early as 1871. Many years later a German peer commented on the reciprocal nature of honour:

“Even in war and between hostile armies, there needs to exist something like loyalty and good faith. In the absence of this principle no pause, cease-fire or capitulation are possible.”

As the centenary of Armistice Day approaches, we would do well to commemorate this lesson.