I have been editing the unfinished book of a poet friend who died after a too-brief fight with cancer. She kept writing until she could no longer think clearly about what she wanted in her poems. I was easily angered for months after she died. This was a surprise to me.

What I was angry about I’m not sure, it could have been that she went before I was ready for her to go, or it could have been that her death was too brutal and crude a reminder of how unfinished, how incomplete my own life will be when it’s time for me to go. (I finish each day by saying to anyone who will listen that I only half got through less than half of the things I meant to do today.)

Or it might be the simmering state I am in as my still-alive parents go further into their nineties and closer to their own long delayed ends. I don’t know. I was short with people who didn’t know my friend had died, and short with people who wanted things done that she would have done but couldn’t now, and I was just plain angry with people. I had been away at the time of her funeral too, and that didn’t help.

Perhaps, like Stevie Smith, who died too early herself, at 69, I imagined for poets and for all of us that death should come as a fitting gift or a payment well earned:

.. a time may come when a poet or any person

Having a long life behind him, pleasure and sorrow,

But feeble now and expensive to his country

And on the point of no longer being able to make a decision

May fancy Life comes to him with love and says:

We are friends enough now for me to give you death ….

– (from Stevie Smith’s Exeat, 1966)

My friend, dying at 71, was serene and vivid as she became sicker and sicker. One of her last poems was titled, For a Good Life, and one of its stanzas went

Let death surprise you

like a bird, leaving

a hologram of light and love

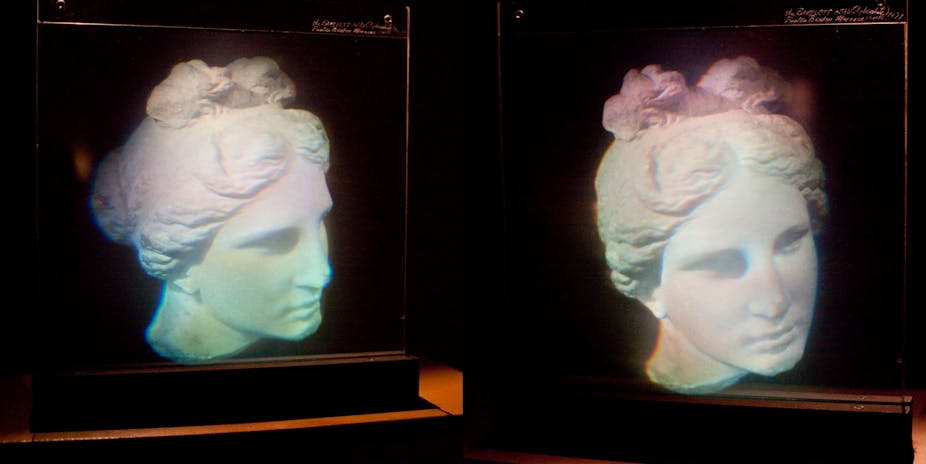

I was surprised that she would write about death as a surprise, and not surprised but enchanted by the image she has left behind of what is left from what was barely there, the movement and sound of a bird.

We have many ways of coming at death. It preoccupies us, and especially poets. Most poems worth their salt are tending to come back to the matter of death. Even when they are poems of love there is that hologram left behind by the complexity a poem can construct in front of us.

Sometimes the beauty and power of the most famous poems of death — those we have from Emily Dickinson, Sylvia Plath, Dylan Thomas, Alfred Tennyson, Keats and others— must be resisted because they can lull and slip us into the too-familiar, the too-quickly-taken-in, into a forgetfulness that is itself a living death. This is not because of something lacking in the poems, it is because we tend to smooth the edges from everything we touch repeatedly. Though, of course, we can’t be near death without being near poetry in hope of feeling its connection with a left behind hologram of light and love.

This return to death, to questions of mortality in poetry, was turned on its head several times over by the very strange and laconic Stevie Smith. Is this life then all there is for us? Is death a transformation? What choices do we have? Stevie Smith wrote, “There is a God in whom I do not believe / Yet to this God my love stretches” (from God the Eater). Like Anne Sexton, Smith took up the tale of the frog prince as one that’s emblematic of the human mortal condition. Her frog prince, in its/his frog life, reflects,

I am happy, I like the life,

Can swim for many a mile

(When I have hopped to the river)

And am forever agile.

And the quietness,

Yes, I like to be quiet

I am habituated

To a quiet life,

But always when I think these thoughts

As I sit in my well

Another thought comes to me and says:

It is part of the spell

To be happy

To work up contentment

To make much of being a frog

To fear disenchantment.

Says, it will be heavenly

To be set free,

Cries, Heavenly the girl who disenchants …

Her frog, of course, succumbs to the rule that frog princes must be “disenchanted” in order for their lives to become heavenly. I can’t help but smile and shiver with horror at what Stevie Smith exposes in our psyches. The tinkle of rhyme ticking down the poem makes it seem both worryingly ominous and merely playful.

My friend, dying, though radiant and powerfully present to the end, was not, as Smith was not, looking to death as a form of transformation, at least not in her poetry. When I read the following lines in another poem she wrote as she died in front of us, I am caught again by the absoluteness of death, and by the hologram of loss that it leaves behind:

Where does a person go

after death, after the shock.

They wander in shadows

always familiar, where at night

they once walked though rooms

touching only the black air

of known spaces

where they bruised, ventured

where some things were most vital

when they were flesh and beloved.

– (unpublished, from His will be done)

Lyn Hatherly’s last book, her new and selected poems, Many, and One, will be published by Five Islands Press in June 2017.