As respiratory clinicians, we have been conducting outreach clinics to the Kimberley, in northern Western Australia, for about ten years, treating children with bronchiectasis, a chronic lung disease in which the breathing tubes in the lungs are damaged.

If left untreated, bronchiectasis can eat away at the lungs and cause devastating long-term effects.

Our research, published today in the journal Respirology, shows how Aboriginal health providers, visiting clinicians, and Aboriginal families can work together to detect illness that may lead to bronchiectasis as symptoms first appear, using local language, stories, and resources.

These resources, including an animated video, highlight that chronic wet cough, in the absence of any other symptom or sign, can be the earliest and often only warning sign of lung disease.

Why early detection is key

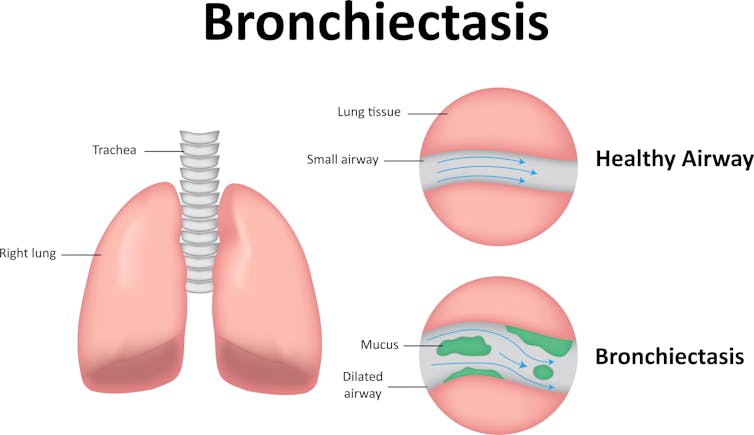

A persistent, low-grade wet cough is often a sign of mucus in the airway that has become infected. Over time, this mucus begins to destroy the lung tissue.

Limiting the extent of lung damage is predicated on timely recognition and management of the chronic wet cough. Treatment may include antibiotics and chest physiotherapy.

If left untreated, the disease can progress and result in a lot of coughing, feeling breathless, losing sleep, feeling worried and helpless, and, eventually, early death.

In Australia, lung infections are the most common reason Aboriginal children are hospitalised. Young Aboriginal children in WA are up to 13 times more likely to be admitted for lung infections than non-Aboriginal children.

More than a quarter of young Aboriginal children admitted with lung infections will go on to develop potentially life-shortening chronic lung disease.

Lung disease is a major contributor to the gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and other Australians. Indigenous Australians hospitalised with bronchiectasis die, on average, 24 years earlier than non-Indigenous Australians with the condition.

Read more: How Australians Die: cause #4 – chronic lower respiratory diseases

Understanding the delay

Each quarter, Perth Children’s Hospital sends a multidisciplinary team to see about 30 children, mostly Aboriginal, who have been referred for specialist care by doctors from across the vast Kimberley region.

We have witnessed the consequences of lung disease being diagnosed too late. We once treated an adolescent Aboriginal boy with end-stage bronchiectasis. He was so sick that he was unable to walk or lie flat. His lung function was less than 25%, well below the threshold for lung transplantation.

This boy was dying from an illness that could have been halted or reversed had someone treated him effectively before his disease had progressed this far. A note in his medical record stated: “Lost to the system.”

Read more: Words from Arnhem land: Aboriginal health messages need to be made with us rather than for us

In our clinics, we noticed a high prevalence of Aboriginal children with lung disease who were seen too late, when preventable lung damage was already permanent.

We found we were not always eliciting accurate histories from families. Specifically, when we asked engaged parents if their children had a wet cough, the parents would say “no” when, in fact, the children did have a wet cough.

Accurate medical history taking is crucial to providing good medical care, as is the provision of culturally appropriate care. But we realised a barrier was preventing us from communicating effectively with families, and preventing those families seeking timely medical care for their children.

From mucus to goonbee

We addressed the issues through partnerships with Aboriginal families, researchers, Aboriginal health providers, and government. We identified the barriers and enablers for both families and clinicians to recognise and manage early lung disease and stop it progressing to serious life-limiting illness.

We interviewed 77 Aboriginal families and clinicians in the Kimberley, and discovered that families had never heard that a daily wet cough for more than four weeks could indicate serious infection.

Coughing was so prevalent among Aboriginal children that symptoms were being normalised.

When families were given culturally appropriate health information, they sought medical help. Parents also gave an accurate history about the presence of wet cough once they better understood the topic.

Culturally appropriate information included use of local language terms – such as goonbee for mucus in Yawuru language – and use of stories or images that families could relate to.

Clinicians can liken the lungs to an upside-down tree, for instance, where the tree trunk is the windpipe, the branches are the breathing tubes, and the leaves are the air sacs where oxygen is transferred to the blood.

We also developed culturally relevant educational resources for clinicians and families, including an animated film and an information flip chart.

Through collaboration, mutual respect, and knowledge translation in our clinics, we are now witnessing little lungs growing stronger, Aboriginal families empowered with knowledge and advocating for their children, and clinicians skilled to provide culturally informed care to children. These observations are being supported by research soon to be published.

By engaging and working together, we will find sustainable solutions to kick chronic wet cough and help prevent Aboriginal children with sick lungs from flying beneath the radar.