After Tony Abbott did everything he could to keep discussion of climate change out of the G20, he has been ambushed almost on the eve of the weekend meeting.

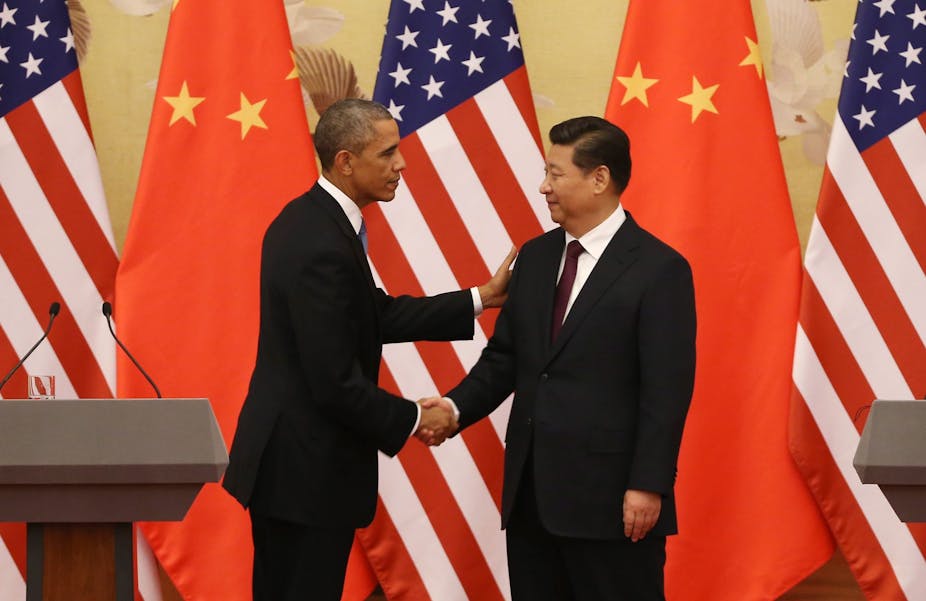

The Prime Minister did not have forewarning of the United States-China agreement on post-2020 emissions reductions, according to government sources. This is despite a meeting with Barack Obama on Monday – at which Obama made it clear he wanted a greater Australian commitment in Iraq.

This climate deal is a big deal. Apart from its detail, it is designed to press other nations to produce their post-2020 targets early for next year’s United Nations climate conference in Paris. The US and China say in their joint announcement they hope to “inspire other countries to join in coming forward with ambitious actions as soon as possible, preferably by the first quarter of 2015”. This is not likely to be Australia’s preferred timetable.

The US is committing to a target of cutting emissions by 26%-28% below its 2005 level in 2025 and “to make best efforts to reduce its emissions by 28%”.

China says it intends to peak its emissions around 2030 “and to make best efforts to peak early”. It also “intends to increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 20% by 2030”.

With Abbott on his way to Myanmar for the East Asia Summit, Environment Minister Greg Hunt issued the government’s response. It was brief and defensive.

“We welcome the announcement by the United States and China to reduce or cap emissions.

"The government is already delivering on Australia’s commitment to reduce emissions by 5% on 2000 levels by 2020.

"We have always said that we will consider Australia’s post-2020 emissions reduction targets in the lead up to next year’s Paris conference. This will take into account action taken by our major trading partners.

"In the meantime, what’s important for Australia is that we have replaced Labor’s ineffective and costly carbon tax with a policy that will actually deliver significant emissions reductions,” Hunt said.

Whether the American and Chinese ambitions will be delivered will only be known years on. But with the world’s two biggest emitters making a determined start, Abbott is left flat footed for the G20, and with a problem for Australia’s position for Paris.

The G20 is an economic forum and Australia is desperate to keep the Brisbane meeting focused on growth and other economic issues.

But climate change has economic ramifications. The joint statement said: “Higher temperatures and extreme weather events are damaging food production, rising sea levels and more damaging storms are putting our coastal cities increasingly at risk and the impacts of climate change are already harming economies around the world, including those of the United States and China”.

The Europeans and the US have reportedly been unhappy with Abbott’s attempts at blocking a climate discussion on G20.

The leaders almost certainly will want to have that discussion and Abbott would be best to go along with as much grace as he can muster. It’s rather the same with Ebola – something else Abbott would prefer to be pushed to the background – apparently there is pressure for something substantial to be said about that.

As for targets, the Climate Institute says that on the American approach, we’d need to reduce emissions by 30% by 2025.

The questions are now: how long will Australia delay the announcement of its post 2020 target; how ambitious will it be; and what will the government say about the policy needed to get there?

If the government believes direct action is appropriate for the post-2020 world, it would be talking about very unambitious target or a highly expensive policy.

The government had another setback on the climate front on Wednesday when the opposition broke off negotiations on modifying the Renewable Energy Target (RET).

The Coalition wants to reduce the current target of 41,000 gigawatt hours of renewable energy by 2020 to around 26,000. Opposition leader Bill Shorten said Labor was willing to accept a figure “between the mid and high 30,000s”.

Pulling out of the negotiations carries some risks for Labor – that it’s seen as unreliable – but the swing in the international conversation also means the government will be under more pressure to compromise.

So far Clive Palmer is holding firm to his pledge not to change the RET legislation. Regardless of Palmer, for investment certainty an agreement between government and opposition is the most desirable route.

Labor wants such an agreement – its letter said it didn’t see any value in continuing discussions “at this point”. It would be surprising – and concerning - if negotiations didn’t restart. But Labor judges it can’t afford to be seen to capitulate.