I recently stumbled upon a post that describes the process of literary translation as “soul-crushing.” That’s news to me, and I’ve been engaged in literary translation for the better part of four decades now. How would I describe it? “Humbling,” yes. “All-consuming,” definitely. But above all, “the most fun imaginable.”

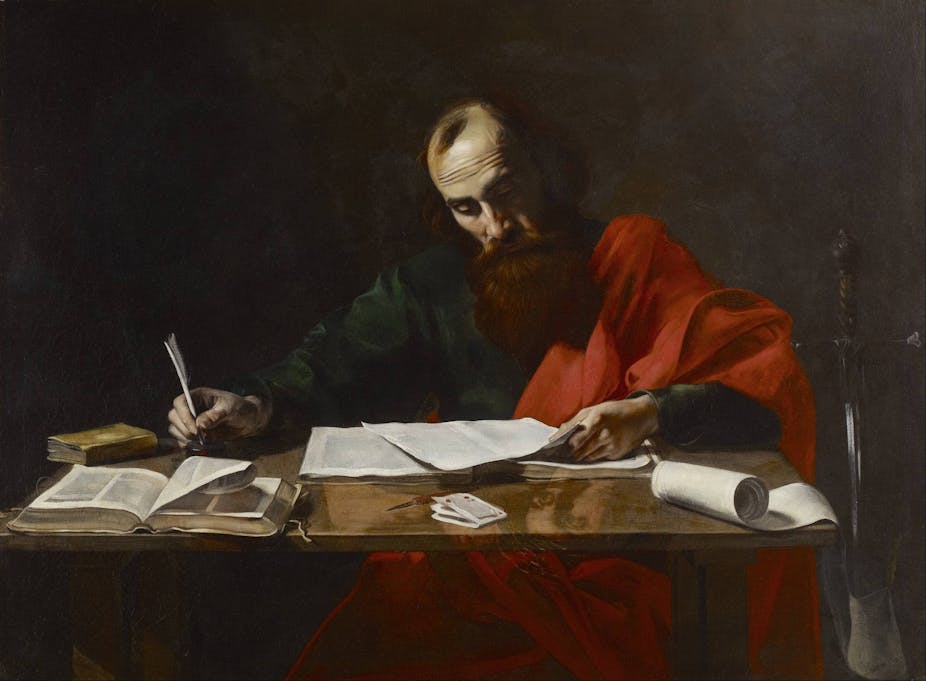

Some may figure that literary translators are a dying breed, like quill pen makers, and assume that computers will eventually take over the job. Don’t hold your breath. Machine translation has a role to play – and no doubt an increasing one – but it is doomed to be literal, to merely skim the surface. Enter “Don’t hold your breath” into Google Translate and you’ll get an injunction to not stop breathing. A human touch is needed to understand layers of meaning in context and to create something pleasurable to read.

Yet the process is humbling, primarily because as a translator, you are constantly made aware of your limitations: there are all the events or interactions described in the original text that you know nothing about, or have never experienced. Or you long to reproduce the wit, rhythm, and beauty of the original, but, for a host of reasons, have to settle for less.

I also find that humility is a practical necessity. When the original makes little sense, often the first impulse is to blame the author. Humility allows you to see the original text in a new light – to appreciate it for what it is, rather than what you may think it’s supposed to be. If you approach a confusing sentence with the assumption that you’re missing something, you’re usually right. So my first rule would be: assume _you _are wrong, not the author.

I’ve collaborated with Japanese author Minae Mizumura on translating two of her books, including the just-released The Fall of Language in the Age of English (Columbia University Press, 2015).

The Fall of Language was first translated by Mari Yoshihara, a professor at the University of Hawaii who also found the publisher. Mizumura then asked me to review the entire book with her – to incorporate changes she made to render the text more accessible and relevant to non-Japanese readers. The book explores the importance of national literature and warns against the unchecked proliferation of English, lamenting that not only nuances, but also “truths” – accessible only in other languages – are in danger of being lost. Translating such a book into English may seem perverse, but it underscores the point that in our age, ideas can spread only if they’re communicated in English.

Over the course of two books, Mizumura and I have worked out a routine.

First, I spend however long is needed to write a draft. Usually I translate alone – most often between the hours of 9 p.m. and 3 a.m.

Once the draft is finished Mizumura and I will review it separately, making tentative changes and formulating questions. Then we get together and spend hours discussing, probing, researching and reshaping.

At the end of the day, I go home and review what we accomplished (once, before a deadline, our “day” concluded at 5 a.m.). When our brains start to go numb with exhaustion, we meet every other day, rather than daily.

The number of drafts varies, but every little improvement, every step closer to the outcome she and I both envision, makes the process one of unfolding joy. All the more so when translating a major author such as Mizumura.

The process of rewriting involves focusing on the author’s main point (or the character’s emotion) and ensuring it’s conveyed as originally intended. It’s like bringing a musical score to life: you pay attention to tempo, dynamics, and phrasing, and above all you seek to end up with not a collection of notes but music. If a turn of speech doesn’t work well in English, it’s better to alter or omit it. Take the example below, from The Fall of Language:

Draft version: Yet just like a constellation of stars in the sky, modern Japanese literature is full of writing that gives the scent of the “reality” of Japan at the time and is also filled with the “truths” visible only through the Japanese language.

Final version: Yet the corpus of modern Japanese literature is filled with such diverse linguistic and literary wonderment that it is a true embarrassment of riches. It is also filled with “truths” visible only through the Japanese language. (p. 153)

Elsewhere, in describing the striking beauty of young Iowans, Mizumura wrote that they looked as if they had stepped out of “Nazi propaganda films.” To Western readers this is a dubious compliment (at best), even if it helps us visualize tall, lithe bodies and corn-yellow hair. She didn’t want to remove the phrase – she’s averse to political correctness, God bless her – so we compromised: “People who I secretly thought would look perfect in Nazi propaganda films as members of the Hitler Jugend – though they might not like the comparison – were walking all over campus with majestic long strides.” (p. 25, emphasis added)

Would I dare make such an insertion totally on my own? Of course not. But unlike Lydia Davis – who recently translated Flaubert’s Madame Bovary – I could consult the author.

These represent only a few of the endless choices that translators, literary or otherwise, are required to make. Much power is entrusted to the translator; tact and discretion is a must. Likewise, respect for the voice and vision of the author, living or dead, is paramount.

And getting a sentence or a bit of dialogue to sound right – so right that it seems inevitable – is deeply satisfying, even exhilarating.

Now, I ask you, what’s soul-crushing about any of that?