John Zorn’s appearance at the Adelaide Festival last week spread across four evenings – totalling over 12 hours. The cost of bringing Zorn and more than 20 musicians from New York to play at the Adelaide Festival and nowhere else, plus Australia-based Elision Ensemble and the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra, was obviously large, and the logistics daunting.

Why Zorn? The Adelaide Festival has made a determined effort switch its focus to a younger audience, leaving some of its traditional audience base feeling alienated.

Festival Director David Sefton clearly feels there’s plenty of Beethoven et al throughout the year to cater for those with classical tastes and is determined to present something different. Zorn fits well with this approach as his musical output covers genres with more appeal to younger audiences, including jazz, punk, metal, and free improvisation. In addition he works with musicians who have strong followings in their own right, including drummer Dave Lombardo from metal group Slayer, bassist Trevor Dunn from Mr Bungle, and vocalist and supreme screamer Mike Patton from Faith No More and Mr. Bungle.

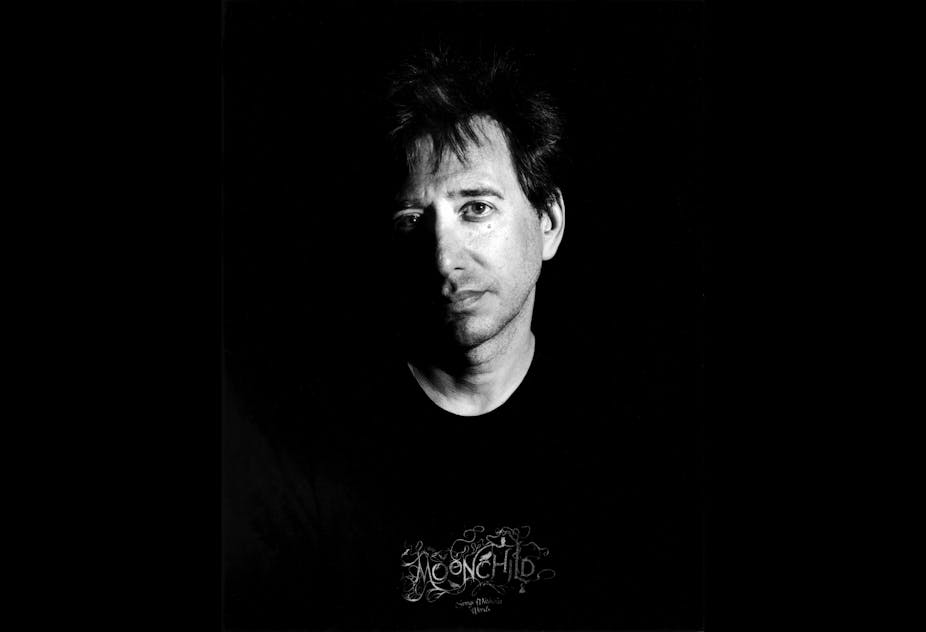

Zorn’s activities as composer, performer, publisher, entrepreneur, record label owner and much more, are so prolific that it is difficult to see how he fits it all in. His easy fluency with many genres of music leaves you wondering who the real John Zorn is.

Or perhaps all of these thing taken together are the “real” Zorn, a product of an age in which, as John Cage said, there are no more fixed tangibles. Identity is fluid, categories are constantly being eroded, and certainty is neither achievable nor desired.

Zorn consciously aligns his work with the historic avant-garde, and his titles contain references to French poets such as Arthur Rimbaud, Paul Celan and Antonin Artaud. Mysticism and esoteric philosophy – both formative influences on the European avant-garde – feature heavily, as do references to Zorn’s Jewish heritage.

Perhaps the most curious parts of his output are the works that fall under the “classical” banner. An entire evening was devoted to them – the Classical Marathon, the second concert in the Zorn tetralogy. (The latter term suggests an undertaking of Wagnerian proportions, a comparison Zorn may dislike.)

It was a long evening of music that was in an almost constant state of disruption, with frequent convulsive gestures and extended instrumental techniques. A brief respite was provided by Zorn’s setting of the melody to the Kol Nidre prayer, fragmented and set against a drone in a manner reminiscent of Estonian composer Arvo Part.

The Masada Marathon drew on Zorn’s Jewish roots, re-interpreted in multiple ways, culminating in Electric Masada, a large ensemble that included Zorn himself on saxophone. The structure of the program was similar on all four evenings, with smaller ensembles in various configurations eventually uniting in a large group performance at the end. It’s a pattern followed by impro nights at The Stone, Zorn’s club in New York’s Lower East Side.

The most immediately engaging segment of the entire series was Essential Cinema, in which four classic films of American Underground film were screened with accompanying music played live. It was a pleasure to see such classics as Joseph Cornell’s 1936 short Rose Hobart, or Maya Deren’s 1946 Ritual in Transfigured Time on a big screen in high quality prints.

Cornell’s cut-up of an old silent movie concentrates obsessively on the face of the now-forgotten actress, with subtle erotic undercurrents in her interactions with a mysterious Indian potentate. Zorn’s surf guitar style soundtrack had a languid, tropical feel; its repetitive structure and the fetishism of the imagery were well-matched.

The weird and wonderful word of filmmaker Harry Smith has an appropriately quirky, almost child-like musical accompaniment. The highpoint though was Wallace Berman’s Aleph, accompanied by a trio, with Zorn playing an extended solo that perfectly matched the frenetic cutting of the film.

John Zorn’s most distinctive musical creation is the improvisation game Cobra. Zorn was the game master, playing the cards that structurally control the course of the performance. A unique innovation is the system of hand signals by which players can communicate with the game master and one another.

It’s fascinating to hear improvisation that escapes almost entirely from the conventions of jazz. With players who are totally familiar with the communication protocols, this kind of improvisation can produce results that are surprising complex and interesting. No groove or riff is allowed to continue for very long. Zorn delights in disrupting musical progress, cutting from one idea to another without transition.

The final concert in the series, Zorn@60, brought together diverse parts of Zorn’s output in one concert. The Song Project had performers Mike Patton, Jesse Harris, and Sofia Rei interpreting songs from ballads and Latin numbers to thrash metal. The diversity of the songs emphasised Zorn’s unique ability as a stylistic chameleon. The extreme scream of Mike Patton left an indelible impression as well as some clear-felling of cells in the inner ear for those without ear plugs. Another high-energy round of Electric Masada brought the final concert to an end.

The musicians performing with Zorn were all of exceptionally high calibre, and there was scarcely anything that could be faulted in the performances, other than the loudness.

The series provided a fascinating insight into the music scene in New York and the fertile mind of one of its most active luminaries. It is, however, only a small part of the full range of contemporary music-making, and Zorn’s version of contemporary avant-gardism represents only one of many possible approaches to composition in the world we live in. Much of Zorn’s music is hard-edged and chaotic, without much space to breathe.

It seems far removed from the natural world, but perhaps perfectly in tune with life as it is led in New York or any similar urban setting. At its best, it’s exhilarating but also exhausting.

Zorn in Oz played at the Adelaide Festival from March 11-14. Details here.

_Are you an academic or researcher? Would you like to review something for The Conversation? Contact the Arts + Culture editor.