In their annual meeting at the United Nations in 2005, world leaders agreed on a common economic agenda. This was to halve – between 1990 and 2015 – the proportion of the world’s population living on less than one dollar a day. It’s been nearly 15 years since this resolution.

The world has certainly seen economic progress but it is not even. And countries in Africa lag behind the global average.

Global wealth has more than doubled from US$170 trillion in 2000 to $360 trillion in 2019. Global wealth per adult is at a record high of $70,850.

Mean wealth per adult in Africa is $6,488. In Mozambique it is as low as $352.

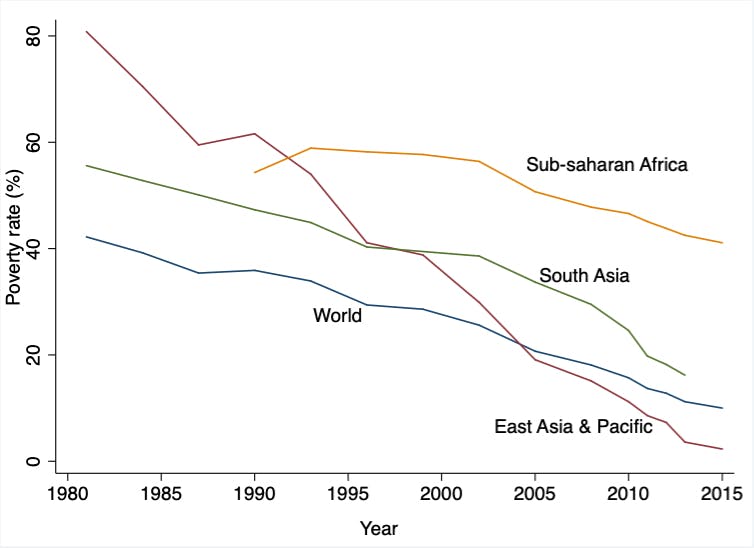

The proportion of the world’s people living on less than two dollars a day (an updated measure of extreme poverty) has more than halved from 35.9% in 1990 to 10% in 2015. But in sub-Saharan Africa the figure still stands at 41%, according to the World Bank. The bank estimates that 87% of the world’s poorest people will live in the region by 2030 if the trends continue.

Life expectancy has been growing by 16 weeks a year so that those born today are likely to live 20 years longer than a child born in 1960. In Africa, average life expectancy remained at a level that the rest of the world passed in 1974 and is rising at a snail’s pace.

The continent still pays up to 30 times more than the rest of the world for generic medicine, despite a world-wide decline in drug prices. And energy prices in Africa are more than three times higher than in the United States.

African countries have missed important opportunities in the past two decades that could have ensured these graphs looked different.

Interlocking problems: debt and aid

In 2004 UK Prime Minister Tony Blair initiated the Commission for Africa, to “carefully study all the evidence available to find out what is working and what is not.”

The Commission’s main findings were:

The problems… are interlocking. They are vicious circles which reinforce one another. …Africa will never break out of the deadlock with piecemeal solutions and policy incoherence. They must be tackled together. To do that Africa requires a comprehensive ‘big push’ on many fronts at once; which requires a partnership between Africa and the developed world…. Africa is very unlikely to achieve the rapid growth in finance and human development necessary to halt or reverse its relative decline without a strong expansion in aid.

Blair then called for two simultaneous actions: forgiving the continent’s debt, and doubling development assistance. This call was partly heeded.

Fourteen African countries benefited from the 2005 multilateral debt relief initiative. That relief saved Nigeria – the region’s largest economy – $31 billion. A host of other countries benefited too, ranging from Benin ($690 million) to Ghana ($2.938 billion).

But these countries didn’t make the most of the relief they’d been given. Debt in many African countries is on the rise again. What’s more concerning is that debt isn’t being incurred for useful purposes, such as plugging the infrastructure gap. Instead, according to an IMF report, the rise is being driven by corruption and mismanagement.

As for aid, since 2005 the flow to Africa has risen by 50%, reaching $49.27 billion in 2017. African countries received more than half a trillion dollars ($0.62 trillion) in aid in the decade and a half after Blair’s appeal.

However, the continent now gets less donor aid per recipient than most regions in the world: an average of 14 cents per person per day. This is because its rapidly rising population size in recent decades is not being matched by the size of aid inflows.

Added to this is the fact that many African countries have failed to stem the flow of illicit money from the continent. An estimated $30.4 billion was transferred from African countries between 2000 to 2009.

Such outflows strip countries of desperately needed financial resources for investment in hospitals, schools and roads.

To stop this trend, Africa needs the help of advanced countries, because some of these countries have been and still serve as havens for illicit funds originating from repressive African regimes and despots.

In “Overcoming the Shadow Economy,” Joseph Stiglitz and Mark Pieth forcefully argue:

In a globalised world, if there is any pocket of secrecy, funds will flow through that pocket. That is why the system of transparency has to be global. The US and EU are key in tipping the balance toward transparency, but this will only be the starting point: each country must play its role as a global citizen in order to shut down the shadow economy—and it is especially important that there emerge from the current secrecy havens some leaders to demonstrate that there are alternative models for growth and development.