When it comes to debating the rights and wrongs of public policies, economists have always held a privileged position. While citizens and less respected social scientists must strive to get their voices heard amid a cacophony of opinions, the claims made by senior economists tend to cut through the noise. For example, controversies surrounding the surging UK housing market involve numerous voices, from charities to journalists to citizens themselves, but the cool, objective tenor of a contribution from the OECD think tank feels completely different. Economists have long dealt in types of knowledge that governments are prone to take seriously.

But at the present historical juncture, something rather more unusual is going on: economists themselves are being placed in the spotlight. Questions are being asked about the nature of the knowledge they produce, the methods they use to produce it and whether they are still teaching the right theories. Also on the table is why so much of what appears in economics journals seems to be so far removed from urgent and everyday economic problems. The financial crisis, and its somewhat underwhelming impact on the core tenets of economics teaching, is at the heart of this.

Student rallying cry

Unusually, much of the reaction against mainstream economics is being led by economics students. New bodies such as the Post-Crash Economics Society at Manchester and the International Student Initiative for Pluralist Economics, made up of student campaigns from around the world, have demanded that economics teaching be reformed. They want it to offer a more nuanced, realistic, interdisciplinary view of how the economy actually works.

The recent sensation of Thomas Piketty’s book, Capital in the Twenty-first Century has given a glimpse of how economics might be done differently, with greater ambition, social urgency and engagement with the current state of capitalism.

This is coupled with a sense of disappointment, that the financial crisis has prompted so little change in orthodox policy thinking. The 2008 banking meltdown is no longer viewed as a major historical turning point, as it felt at the time. Now it is more used as an excuse by governments to pursue certain neoliberal agendas even more feverishly, such as further deregulating labour markets and reducing public spending.

Many people feel that the failure of economics to refresh itself and the failure of governments to broaden their policy horizons are related to one another.

A new PPE

It is with these concerns in mind that Goldsmiths, University of London (where I am a senior lecturer) recently announced a new degree in Politics Philosophy and Economics (PPE), which would offer an explicit challenge to the status quo.

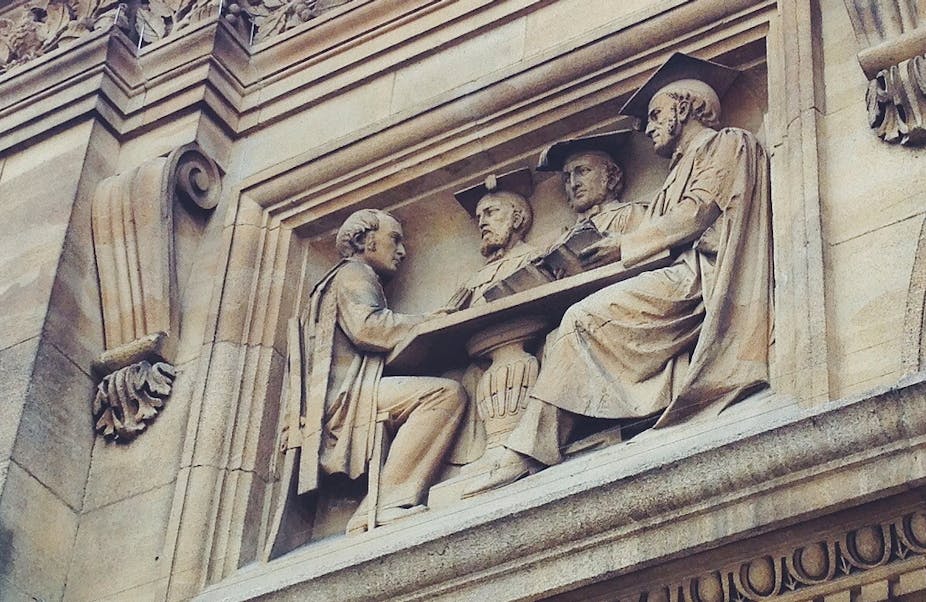

This is a very well-known combination of disciplines, thanks to Oxford University’s famous PPE degree. Oxford’s PPE degree has become seen as a ticket into the political establishment – both David Cameron and Ed Miliband studied PPE at Oxford. Since Oxford first introduced the PPE degree in the 1920s, a number of other UK universities, including Warwick and Manchester, have offered similar degrees.

Now the rise of student movements against orthodox economic teaching suggests that there is a younger generation emerging that wishes to ask some difficult questions, that mainstream economic theories don’t offer answers to.

We need young people to try and understand economic life as a set of social, cultural, political and monetary processes and institutions.

Learning from other disciplines

This is partly about bringing “heterodox economics” – theories that offer an alternative to the mainstream – into the core of how the discipline is taught. Drawing on Marx, Keynes, Schumpeter, Hayek and Minsky, heterodox economists stress that capitalism is a dynamic and uncertain political-economic system, which requires certain forms of power inequality in order to be stabilized for any length of time.

This immediately poses political questions, meaning that the study of the economy cannot be divorced from the study of politics, ideas and history. This means allowing the “P”, the “P” and the “E” to speak to each other, rather than simply offer three separate disciplines in tidy, separate boxes.

The basic tenets of mainstream economics were laid down between 1870-1900. Of course there have been theoretical innovations since. But much of economics’ claim to the status of a “science” rests on the fact that its contributors speak a rigid and tightly codified language.

What people are now asking is whether that language actually tells us anything about the world they read about in the newspapers and see on their television screens or, for that matter, experience via their mounting debts and government cuts.

There are other ways of being “scientific” about what goes on in the economy. Anthropology, sociology, political science and cultural studies are also disciplines which study economic life. Psychology has already been a more celebrated source of interdisciplinarity, thanks to behavioural economics.

We believe that for students who are genuinely curious about economic issues, want to ask difficult questions, and not simply follow the tramlines that were laid down a century ago, a new interdisciplinary approach to economics is much-needed.