The DNA of Albert Perry may change the story of human origins. Perry was an African-American born into slavery in South Carolina. An analysis of the DNA of his descendants produced results that came as quite a surprise and have raised questions for geneticists around the world.

It turns out that Perry carried a very different type of Y chromosome, never seen before. Every male has a Y chromosome, which is a piece of DNA inherited by sons from their fathers. But, unlike most DNA, the Y chromosome is not shuffled as it is passed down, and changes only slowly through mutation. Tracking these mutations allows scientists to create a genetic tree of fathers and sons going back through time.

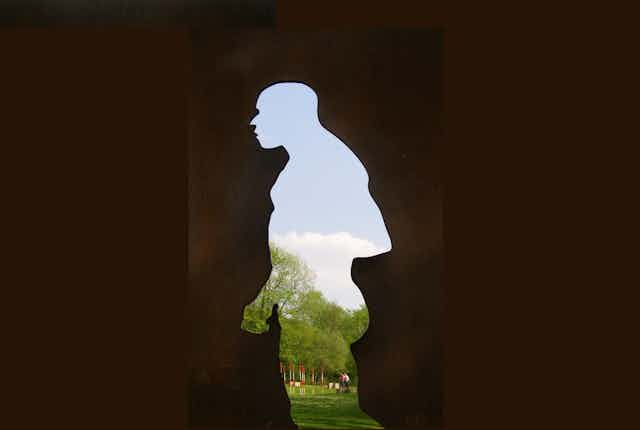

As a man may have several sons or none, some branches of the genetic tree die out each generation, while others become more common. Going back through time it is therefore inevitable that all modern Y chromosomes must descend from from one man at some point in the past. He has become known as “Y-chromosomal Adam”.

This Adam was not the first man, or the only man, from his time to contribute to modern human DNA. It is just that, by chance, his Y chromosome was the only one to survive until today.

What is surprising about Perry’s Y chromosome is that it did not descend from Y-chromosomal Adam’s. Or rather that the established “Adam” has lost his title to a new “Adam”, further back in time, where Perry’s branch split from the tree (see figure). While the former-Adam is estimated to have lived around 202,000 years ago, the revised one is thought to be about 338,000 years old.

To find where Perry’s Y chromosome may have come from, samples from around Africa were tested. Several more from Perry’s branch were found amongst the Mbo people of Cameroon.

So can this tell us anything about human origins? Central Africa contains Y chromosomes from both Perry’s branch and the former-Adam’s branch, while the rest of the world has only been shown to contain the former-Adam’s branch (with the exception of Perry himself). This suggests that our revised Adam may have lived in Central Africa.

The oldest-known “modern human” bones are from East Africa. But if Adam lived in Central Africa, does that mean that modern humans could have originated there? Again, it is hard to say. By looking further into the genetics of modern people, the picture becomes even more complex.

It so happens that, just like the Y-chromosome is passed down only from father to son, there is a piece of DNA which sits in a different part of the cell called mitochondria, that is passed down only from mother to her children. Tracing back this DNA in a similar way, leads us to a “Mitochondrial Eve”, estimated to have lived about 190,000 years ago. Eve possibly lived in south-eastern Africa. But modern humans have DNA both from Adam and Eve.

Despite these apparent contradictions, it is possible that modern humans descended from a single localised population, and that geographical differences in diversity today are due to spread and extinction in the intervening years. But it could also be that many of the genetic and cultural ingredients that produced modern humans existed in different parts of Africa, drifting and spreading until they came together and, by a mixture of luck and natural selection, became the combination that would out-compete their relatives to spread to the rest of the world.

One way or another, around 200,000 years ago, bones appear that are indistinguishable from today’s. But that is 140,000 years later than the estimated age of the new Adam, leading to the question: was he even “human”?

Answering this is tricky. There was no single moment when we became human, but rather a gradual process. On an evolutionary timescale, Adam was very recent, and even if he was not “anatomically modern”, he could probably walk down a street today without raising too many eyebrows.

Given the scarcity of Perry’s branch and the lack of diversity within it, it is also possible that the revised Adam could have been an ancestor of two sub-species (or even species). Could one have become modern humans, while another produced a cousin? What if, long after modern humans had become established and started to spread, they should meet and interbreed? Like all our other close relatives, these cousins eventually disappeared, but maybe they left traces, such as Perry’s Y chromosome, in the modern gene pool.

This may sound shocking, but it would not be unprecedented. When modern humans spread from Africa to Eurasia, they met another cousin, the Neanderthals. Fossils with features from both species have long caused debate, and recently genetic evidence has suggested that today’s non-Africans owe 1 to 4% of their ancestry to such interbreeding, although no Y chromosomes have yet been identified.

So, like many discoveries, Perry’s Y chromosome raises more questions than it answers. It will doubtless be fascinating to watch our understanding evolve as the genetics of more individuals, modern and ancient, from more locations are added to the picture.

Correction: This post was modified to reflect that DNA test was performed on two of Perry’s descendants, rather than on Perry.