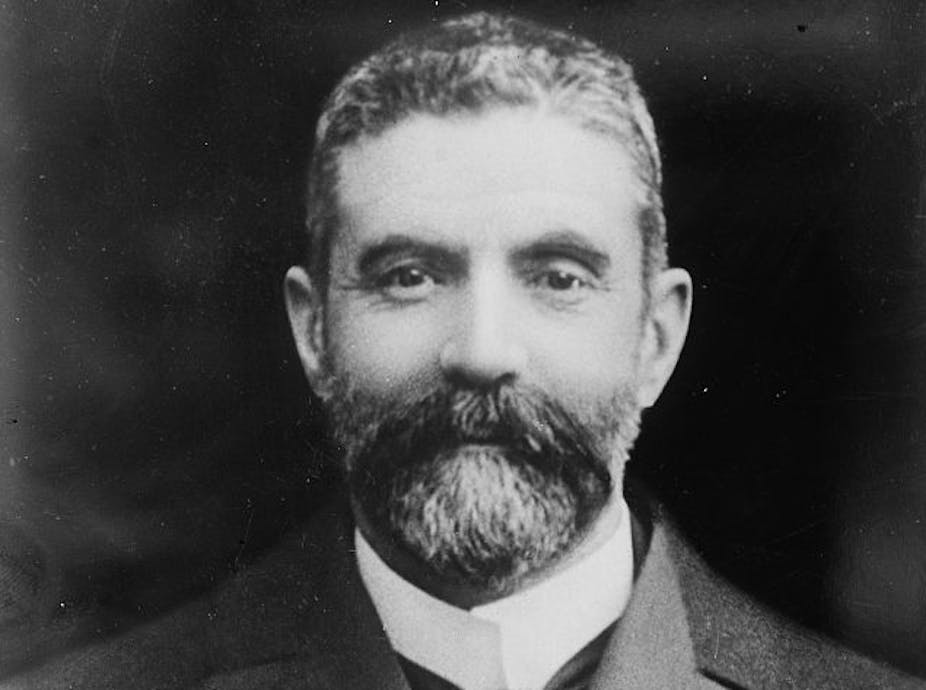

How do you rally a people to accept the responsibilities of national security, the burden of their own defence? Here’s how then-prime minister Alfred Deakin did it in 1907:

We are a free people, with political equality and sole authority in a country where all have the opportunities to possess homes of their own. Our position as free men in a free country casts on all the responsibility of undertaking our defence.

Deakin’s words are a snapshot of current Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s problem. Unlike Deakin, an architect of Federation, Abbott has no language for reaching out to the Australian people.

Deakin’s 1907 defence statement was delivered in parliament, a symbolism that stressed his accountability and exposure to his critics – within parliament and without. Abbott’s national security statement earlier this week was delivered in a small room at Australian Federal Police headquarters, filled with a carefully selected audience of political allies and the heads of the security agencies.

Journalists were not allowed to direct questions to Abbott. He warned that “we cannot allow bad people to use our good nature against us”, apparently not least those within Australia. This included “Muslim leaders”, whom Abbott implied may not be sincere when they describe Islam as a religion of peace. Abbott’s default instinct is division, and his words reflect it.

But from one speech to the next, Deakin spoke an inclusive language, drawing the Australian people into the task of their own government. He respected that “the hands of people” were creating a Commonwealth “for themselves”, as he declared following Federation in 1901. Deakin knew what he believed in; it helped him to believe in himself and to survive three terms as prime minister between 1903 and 1910.

By contrast, the Abbott government’s first budget was dominated by harsh measures delivered without warning. Abbott could not offer a compelling narrative to justify cuts to pensions or university funding. Abbott lamented that the government needed to clean up “Labor’s mess”, hardly a compelling or inclusive appeal.

Sifting the bullet-point clichés and slogans of Abbott’s statements, the only vivid appeal to inclusion was triggered by fear. Faced with a backbench revolt and a leadership spill, Abbott desperately – and inaccurately – asserted that it was for the people to make or unmake his prime ministership, not his despairing Liberal colleagues in the party room. Lost for words, Abbott resorted to bullying the backbench by slogan.

Abbott’s post-spill promises were equally unconvincing. He repeated sound bites of contrite script. He claimed to be chastened and changed; he would be “different” and “do better” – but do what differently? What, precisely, will be better?

Deakin’s rhetoric dealt in specifics. He moved from one substantive reform to the next, arguing each case in detail as the Commonwealth accrued what he described as its “great institutions”. These included the establishment of the High Court of Australia, inaugurating a system of arbitration of industrial disputes between employers and employees, and fighting through the enervating political trench warfare of implementing the tariff system.

Deakin invested the dense web of bureaucratic tariff schedules with the aspirations of a nation. He promised to ease the stress of a people worn by the political divisions and economic suffering of the 1890s. By protecting jobs and industries from foreign competition, he declared in 1903 that the “Australian tariff” would inaugurate an era of “fiscal peace”.

A modern audience would be shocked at the depth of Deakin’s speeches. Opening his 1903 election campaign in Ballarat, Deakin was on his feet for two-and-a-half hours. Deakin said it was his duty:

… to call your attention to the number and magnitude of the interests over which you have control.

He was the instrument of their self-government and, in outlining the responsibilities they shared, Deakin said he would rather “tire your patience … than mislead your sense”.

Deakin respected the intelligence of his audience. His speech was received with “intense enthusiasm”. Even his dedicated political enemies at the Melbourne Argus newspaper conceded the speech reflected his skills as “a supreme word-spinner”.

Presented with an opportunity to set out his policy ambitions at the National Press Club earlier this month, Abbott struggled to describe an invigorated policy framework. A week later, ABC 7.30 host Leigh Sales posed Abbott a blunt question:

Who are you?

Sales offered Abbott a chance to describe his ideals, to tell the people what he stood for. Abbott merely promised to undo his inept “captain’s calls”, including the future awarding of knighthoods. Abbott reminded viewers of his errors of judgement.

Democratic government is an endless negotiation of the governed and their representatives. Trust is shaped in words; deception is unmasked in the slipshod abuse of language. A lack of substance is exposed in the fumbling refuge of cliché and repeated slogan.