The major missing factor in debates on cutting welfare spending – as has been flagged by social services minister Kevin Andrews – is the limited and falling demand for labour. Labour market figures give the lie to the need to target working-age payment recipients as the issue.

The problem is not supply-side inadequacies but the demand for labour: there are far too few jobs on offer.

This factor undermined the thrust of Patrick McClure’s original review of the welfare payments system in 2000, which was labelled “Welfare to Work”. It makes a nonsense of repeating the exercise.

The earlier strategies did not decrease the numbers on payments: it just moved them to other payments, as is shown in the gradual increase in recipients overall. The numbers fell when more jobs were available and rose as the global financial crisis cut in and job numbers fell.

In December 2013, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) recorded [716,000 unemployed people](http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/cat/6354.0](http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/cat/6354.0) who had actively looked for work in the previous fortnight, up 15,000 from the previous month. These figures do not fully overlap with 338,660 November Newstart Allowance recipients, as some of those had a few hours’ work in the same fortnight. But, put together, the figures show official job seekers numbered around at three-quarters of a million.

This estimate does not include those discouraged from actively looking for work and those wanting to change jobs or find more work. So maybe the real job-seeker numbers are close to one million people looking for work.

One of the basic questions that is not asked is whether suitable paid jobs are available and accessible for those on payments that are assumed to encourage entry to paid work. The ABS data on job vacancy trends suggests some serious and increasing lack of vacancies.

Total job vacancies in November 2013 were 140,000, a decrease of 0.3% from August 2013. Private sector vacancies numbered 129,500 in November 2013, a decrease of 0.1% from August 2013. Job vacancies in the public sector totalled 10,500 in November 2013, a decrease of 3.6% from August 2013.

Another set of indicators tells the same story of too few jobs and falling vacancies.

Here we learn that:

Job vacancies in Australia decreased to 124,786.50 in December 2013 from 125,657.20 in November 2013. Job vacancies in Australia averaged 134,517 from 1999 until 2013, with an all-time high of 261,394 in April 2008 and a low of 56,560.60 in July 1999.

These figures show serious gaps between the numbers of jobs and job seekers. There appear to be at least seven potential applicants per vacancy, without including employers’ specific requirements.

These conditions make it likely that employers will choose able-bodied people without kids with recent employment experience and who are not depressed by too many failures. Such discrimination is hard to identify in situations where labour demand is so far below supply that most of the officially unemployed will miss out.

The old McClure strategies did not increase participation, nor will they now. The main strategy was to reduce the incomes of possible job seekers by moving them off higher payments that recognised their difficulties in finding employment (Disability Support Pension and Parenting Payment) onto Newstart. The theory was that a lower base income and tighter tapers on added earned income would create the incentive to find (non-existent) paid work in a crowded market.

The failure of the tactic is shown clearly in the experience of sole parents after the McClure review. From 2006, those on the Parenting Payment were registered as job seekers when their youngest child turned six. They were moved to Newstart when the child turned eight.

About 120,000 existing recipients were grandfathered onto the higher payment, but most of them were recently moved to Newstart under the Gillard government. This change ignored the lack of evidence that those sole parents already on the lower payment had benefited from the earlier move by finding jobs.

In contrast, those left on the higher payment mainly had part-time work, which fitted with study and children’s needs. The move to Newstart meant their incomes were substantially reduced and they needed more work to make it up. Some dropped out of training as they had no support or time.

Data on the 40,000 who were moved earlier to Newstart is sparse, but the indications are that they are less likely to have part-time jobs than those who were on the higher payment. I covered this change in detail last year.

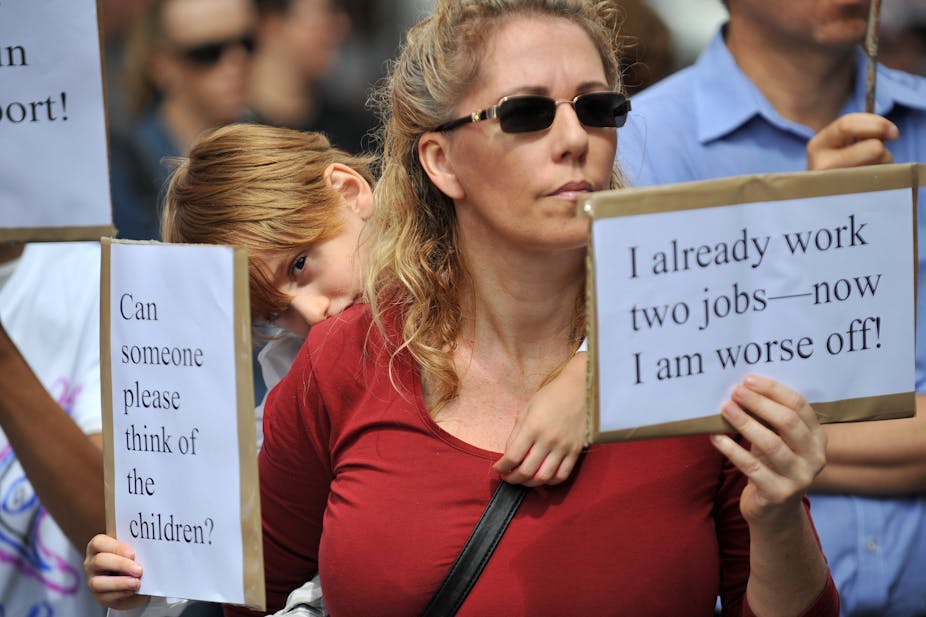

The claims by the government that the problem is the unemployed, not the lack of jobs, is a major con, too often blindly accepted by the media and the public. Cutting people’s payments does not increases their participation level in tight job markets. Their very low payments often fail to cover the costs of looking for unlikely jobs.

All Newstart recipients subsist on widely acknowledged inadequate incomes. Even the Business Council of Australia believes the current Newstart rate (A$250 a week) is too low. The payment no longer meets the community standard of adequacy and is, in itself, a barrier to people finding their way back into the workforce.

The same payment also covers many who are not looking for paid work because they are in training, sick, have temporary disabilities, are volunteering because of age, or have care responsibilities. Half of the people on Newstart are living in poverty but not looking for work, which is one reason given for keeping it so low. More are now also single parents and have some levels of disability.

People living on part-time paid jobs or doing unpaid ones need more income support. Andrews’ review should tackle the issue of funding a rise in the basic payment to provide an adequate basic income.

The review should also look at recognising other forms of time contributions. Higher payments can supplement the earned income of those with part-time work and other responsibilities or limits on their capacity to work. We need to think about ways to redistribute the benefits of both paid work and unpaid tasks and contributions to create wider well-being.