Rumours of the death of FIFA have proved premature. The announcement that the 2022 World Cup in Qatar has been moved to December after facing down opposition from European football clubs and leagues signals that the global game is not going to get a potentially transformative confrontation and puts the sport’s governing body in a renewed position of strength.

It hasn’t been an edifying spectacle. The clubs had been angered by news that FIFA’s own taskforce had recommended that the Qatar tournament should be moved away from the traditional end of the European season in May and June (it turns out that it wasn’t a good idea to expose players and fans to the extremes of a Middle Eastern summer).

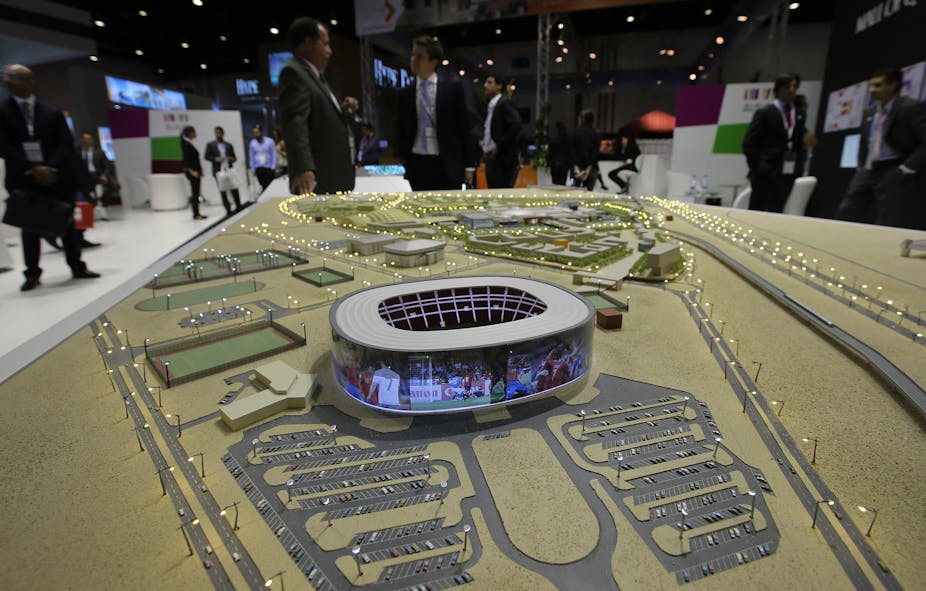

And FIFA has been struggling to come up with a response to extreme working conditions for the thousands of migrant workers that have led to accusations of human rights abuses during construction of the stadiums. Death rates have been startling, and health and safety problems threaten hundreds of other workers. Clearly the spectacle of footballing stars and full stadiums is more important.

Winter break

FIFA seems to find itself mired in scandal at every turn and as it slowly comes clean on corruption around its bidding processes, the Qatar stand-off marked a crossroads.

Greg Dyke, chairman of the English FA, and Premier League CEO Richard Scudamore both lambasted the recommendations about the timing of the World Cup. In particular it would disrupt the frantic Christmas schedule, which is seen as a unique selling point of English league football.

In addition, the lobby group of European football clubs, the European Club Association (ECA), also lined up to criticise the proposal. The president of the ECA, Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, called for FIFA to compensate clubs for the disruption. So here we had a battle brewing between FIFA and the clubs who pay the vast majority of the salaries of the footballers who grace the World Cup. It turns out that money really does talk. FIFA announced that they would triple the amount of compensation to clubs. The clubs have conceded.

Clubbing together

It is mightily significant that FIFA has prevailed here. It should not be forgotten that a similar power struggle occurred 30 years ago when elite European football clubs challenged UEFA over its administration of the European Cup. FIFA may have had to hand over some cash to get its Qatar tournament, but back then UEFA ceded some power to the clubs in order to retain legitimacy. This helped create the current situation of a small number of clubs capable of winning national leagues and the Champions League (UEFA’s replacement for the European Cup).

The president of AC Milan and former Italian prime minister, Silvio Berlusconi, led the agitation against UEFA:

The European Cup has become a historical anachronism. It is economic nonsense that a club such as Milan might be eliminated in the first round. It is not modern thinking

The format of the European Cup had meant that the larger, prestigious clubs could conceivably be knocked out in the early rounds. Finals in the 1970s and 1980s highlight the more egalitarian competition in place. For the likes of Silvio Berlusconi, being knocked out in the early rounds meant losing considerable television income. He wanted a league format to ensure more television income and more opportunity for his team to progress.

Leagues ahead

AC Milan was part of the G-14 group of elite clubs which later became the ECA. These clubs were actively challenging the power and authority of UEFA. The elite clubs were threatening to create their own breakaway league; they knew that they were the box office draw for television audiences. UEFA eventually succumbed and established the Champions League in 1992 which gave the larger clubs more income and more opportunities to progress.

It should not be forgotten that the Premier League was also established in the same year as the Champions League, formed by a breakaway of the elite clubs from the Football League. It took control of its own finances and, rather than redistribute throughout the league structure, Premier League clubs retain more of the income for themselves.

The commercial transformation of the Premier League and Champions league enabled clubs in elite leagues to attract the best players from around the world; the very players who will be playing in a World Cup. These players are what attracts the sponsors, fans and TV viewers to the tournament. This was the ECA’s trump card. In snapping up FIFA’s financial compensation, it seems the ECA didn’t realise the power it had, or gave way to concerns that the image of the World Cup is more important than the European competition. Either way, elite football clubs may well have missed a trick to dent the FIFA’s armour and accumulate more power for themselves.

Former England defender Gary Neville said that football should “get over” the decision. But far more was at stake than just some minor disruption. FIFA often seems a dogmatic organisation – and as it forced through a much-criticised tournament, you wonder if it also sees itself as having some kind of papal infallibility. It has certainly demonstrated that FIFA can still hold the whip hand – and is ever more unlikely to open itself up for democratic reform anytime soon.