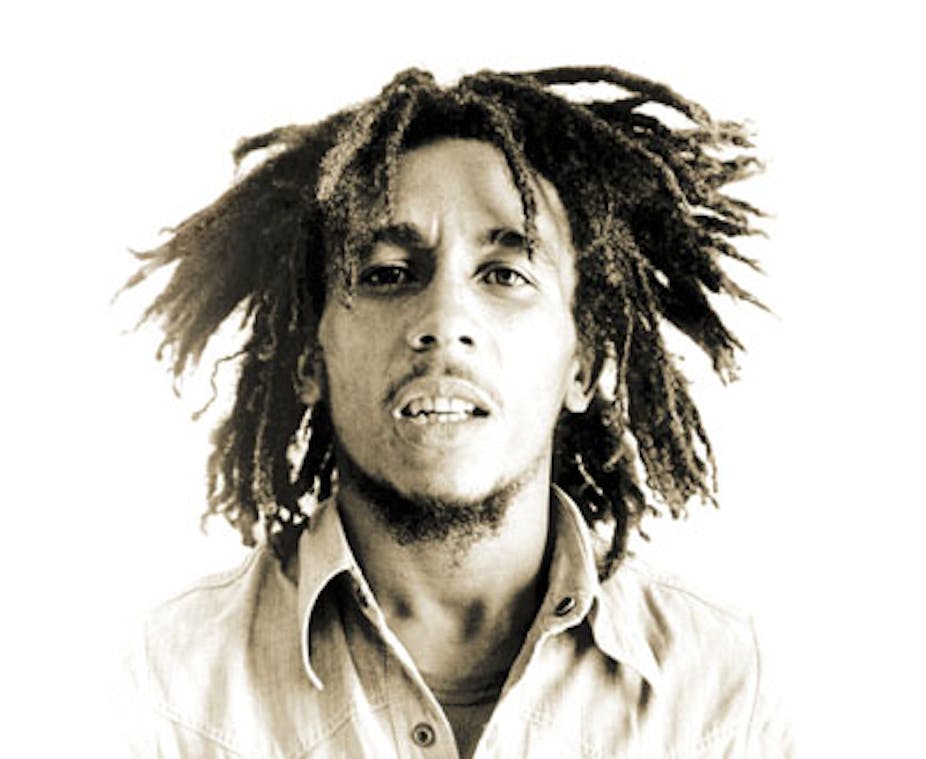

Dear Bob,

It’s been 35 years since your death, yet no other singer or songwriter has articulated both the condition of the marginalised and the humanistic potentials of psychic decolonisation more than you. And, arguably, no other public intellectual has illuminated the role racism and classism play in shoring up the neocolonial political economy as poetically as you have.

When people gathered together to resist not being seen as people, as they did in Tahrir Square in Egypt, or at the beginning of the Arab Spring in Tunisia, they called on your rhythms, singing “Get up, stand up”. When the agony of downpression – the rest of the world outside Rastafarianism know it is as “oppression” – exceeds me, when images of social equality recede, I draw from your beats. Some say your oeuvre has become cliché.

This is more reflective of the way in which people listen over the meaning of your words than of your ideas becoming irrelevant. Still, what remains after all these years is your spirit. A spirit able to use words as transport. A spirit able to use the sound of poetry set to music to create images. Most importantly, a spirit able to shift affect from numbness to something near empathy, so that thought and recognition may rise in tandem with the concrete jungles you expose.

In spite of what you left us with, Bob, I am growing weary of backward steps in consciousness, of political regressions that grow the System – “Babylon” as Rastafarians call it – and by the daily slaughter of unprivileged people’s lives and bodies. I am, increasingly, relentlessly, thinking about psychic revolt, a distinctive way of thinking and feeling that fuels our acting against Babylon.

It is imperative for us to interrogate the world by going into our interior with integrity, made possible by scrutinising our relationship to social realities. I think this is what you meant when you implored us to emancipate ourselves mentally in “Redemption Song”.

French feminist philosopher Julia Kristeva characterises revolt as a fusion of “psychic revolt, analytic revolt, artistic revolt”. Together it produces:

a state of permanent questioning, of transformation, change, an endless probing of appearances.

But she pushes this idea further, Bob. She proposes that real revolt, not revolutionary movement which so often stalls, requires “unveiling, returning, discovering, starting over” through a process of “permanent questioning that characterises psychic life and, at least in the best of cases, art”.

Growing psychic life

This brings me to why I’m writing you so late in the day of our exodus. It’s time to put ideas from liberation psychology, specifically those about how to grow psychic life, together with roots or conscious reggae music to carry on the unfinished business of decolonisation.

Such a pairing could help us enter into the state of mind where we question our social world unrelentingly and, most importantly, our contribution to its production.

We can create reggae dialogues, new ways of engaging psychological defences to liberation, which could evolve the work conscious reggae music set out to do. This form of dynamic dialogue could also aid our recognition that on their own neither inquiry nor socially conscious art (decoupled from analyses of realities it critiques) are ample responses to the traumas people face. Together, theory and art may cultivate conditions in which psychic space opens up allowing us to squarely confront Babylon’s harms.

I see this as a contribution to the development of psycho-aesthetic scholarly activism, the kind of work Barbara Duarte Esgalhado is starting to do. This work advocates a kind of perceptual engagement that synthesises the different ways in which we come to know, to perceive and source the power to stand up.

Also think of the work of Brazilian theatre director Augusto Boal. Imagine Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed, which is a participatory theatre that fosters democratic and cooperative forms of interaction among participants, taking place in people’s minds, Bob. You know how reggae music fosters what philosopher Frantz Fanon promotes as disalienating shifts in consciousness. Incorporating the affective charge of your art might make people’s social and political engagement all the more powerful.

Wise but incomplete strategy

Given your ideological commitments, I believe that using the entertainment industry as your cultural intervention was a wise strategy but an incomplete one. Had you lived longer I would have hoped, given the importance and reach of your work, that you, like intellectuals in the academy, would gift your work to the cultural commons.

Ballads such as “One Love”, “No Woman No Cry”, “Three Little Birds”, “Could You Be Loved”, “Waiting in Vain” and “Turn Your Lights Down Low” could remain in the commercial catalogue benefiting the Marley Estate financially. Poetry and philosophy such as “So Much Things to Say”, “Running Away”, “We and Dem”, “War”, “So Much Trouble in the World”, “Guiltiness”, “Babylon System”, “Zimbabwe”, “Coming in From the Cold” and “Redemption Song” could be released immediately into the creative commons (public domain) available for collaboration with other cultural workers, gratis.

I’ve been thinking about this, Bob, because I’d like to create a reggae opera to tell the story of how downpressors – middle class people who don’t walk with the downpressed – turn a blind eye to their experience in Jamaica and elsewhere. I’m imagining hosting intimate groups where we encounter audio-visualscapes of the voice of the downpressor paired with images created by your music. If done right, the reggae opera experience could arouse psychic revolt catalysing conversations not routinely had in the (post)colonial world.

For the past eight years I’ve listened to contemporary reggae music searching for the consciousness of Rastafarian ideology, a voice that hammers home anti-racist, anti-classist possibilities. I have yet to find the equivalence in tone, image and feel to what you produced, for example, in “Guiltiness”:

These are the big fish (These are the big fish)

Who always try to eat down the small fish (Just the small fish)

I tell you again.

They would do anything

To materialise their every wish

Oh yeah.

But wait!

Woe to the downpressers.

They’ll eat the bread of sorrow

Woe to the downpressers.

They’ll eat the bread of sad tomorrow

Woe to the downpressers.

They’ll eat the bread of sorrow

Oh yeah. Oh yeah

Bob, juxtaposing your song against narratives of downpressing could, if perceived deeply, crack open collective consciousness about the psychic underpinnings of Babylon, dismantling our denial of its structures.

From there we can start to build a humanising world. The question is: How can we release your radical thought into open space where it can work, in solidarity, with others?

In hope, Deanne

“An Open Letter to Bob Marley: Time to Create Reggae Dialogues” by Deanne Bell, was originally published in Obsidian: Literature & Art in the African Diaspora Vol. 41, No. 1&2 (2015): 107-110.