A report published today in Nature by Yohannes Hailie-Selassie and co-workers outlines the importance to our evolutionary story of some very ancient foot bones discovered recently in the Rift Valley of northern Ethiopia.

The findings matter because the beginnings of the human evolutionary line remain murky.

We know that humans shared a common ancestor with chimpanzees in Africa 6-7m years ago before setting off on our own evolutionary journey.

Unfortunately, we’ve only a handful of fossils from around this time, and those found are not universally accepted as members of our kind – the two-footed apes, or hominins.

We are sure though that the package of upright posture and walking on two feet – bipedalism – was the first major change to set our ancestors on their evolutionary journey to us.

Bipedalism is the defining feature of our evolutionary branch, and by definition is shared by all its members: hominins are the “bipedal apes”.

On ya feet

The shift to two-footed walking was profound and unique, setting us apart from all other mammals, and is in some ways akin to what we see in birds.

Bipedalism accounts for many of the unusual features of our own bodies compared to the rest of our primate cousins.

It led to many changes including our shortened and curved spine, short and broad hips, long legs, large knee joints that sit beneath the middle of our bodies (our knocked knees); it changed the size, arrangement and action of our hip muscles; it altered the way our internal pelvic organs are suspended as well as the internal and external positions of our reproductive organs.

Bipedalism set our ancestors on an evolutionary path that would ultimately see them occupy every nook and cranny of the planet; it laid the foundation for a profound shift in diet that included a reliance on hunted animal flesh obtained using manufactured tools; and it dramatically shifted our sex and family lives.

Dem bones

It is into the above context today’s Nature report is published.

Foot (metatarsal) and toe bones (phalanges) recovered from the Burtele site (in the Afar Regional State, see map above) provide a rare glimpse of the form and function of the early hominin foot and force a major rethink about how bipedalism evolved.

Surprisingly, the bones show an unusual mix of human-like features – confirming they’re from a hominin – similarities to gorilla foot bones, and even some likeness to monkey feet.

The shafts of the foot bones are somewhat curved, whereas our foot bones are straight; a change thought to be associated with our lack of a tree-climbing lifestyle.

The big toe is small and divergent in the Burtele foot, or has grasping capabilities like the gorilla’s big toes.

In humans and many extinct hominins, the big toe is large and sits in-line with our other toes, lacking a proper grasping function.

At the same time, the new specimen has a somewhat arched foot, providing stability during walking, and shows the signs of “toe-off” – that part of our walking cycle when the big toe gives our foot extra thrust as we lift our leg from the ground.

The fourth toe of the Burtele foot is unusually long for a hominin, or even an ape for that matter, and more closely resembles the long toes of a monkey.

With an age of 3.4m years old, all of this is a big surprise.

The Burtele foot is not from the base of our evolutionary tree; it comes from half-way along, and samples a time from which we already have quite a lot of fossil evidence.

Its similarities to gorilla and monkey feet are remarkable, but can be explained by a process called evolutionary convergence – the process whereby features evolved independently owing to similarities in lifestyle, rather than features inherited directly from an evolutionary ancestor.

These similarities shouldn’t be dismissed as mere evolutionary noise. They offer us insights into the complex lifestyles that existed millions of years ago on the African savanna and the diversity that must have existed in our own evolutionary tree.

I loved Lucy?

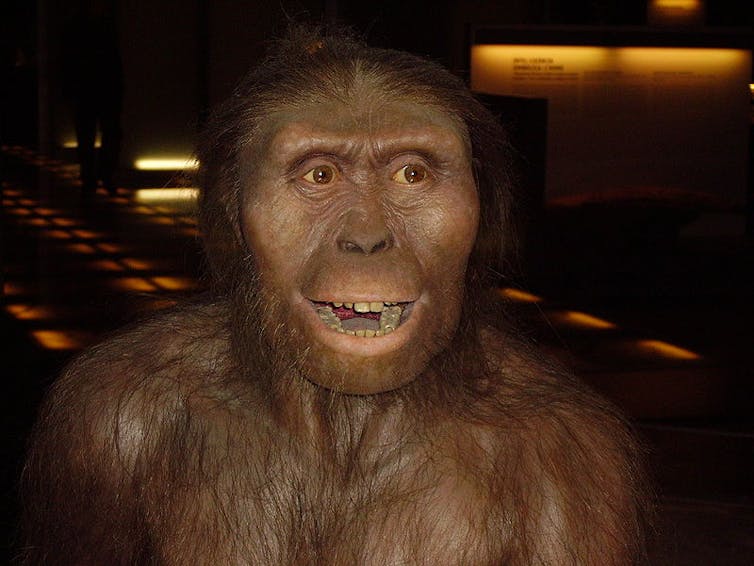

The age of the Burtele foot means that the species it represents shared the savanna with another well-known hominin – Australopithecus afarensis – made famous in the 1970s by the discovery of the partial skeleton dubbed Lucy.

Lucy’s kind had a foot much more like our own. That said, we do see some features also suggesting a tree-dwelling component in its lifestyle, such as curved toe bones.

But Lucy’s foot was structurally well-adapted for ground dwelling and walking on two feet.

The Burtele hominin – which cannot be classified in a species as yet – must have had a lifestyle very different to that of afarensis, and one with similarities to the gorilla as well as to African monkeys.

To its discoverers the Burtele hominin harks back to the beginning of the human line, and may represent a very primitive hominin – Ardipithecus – which could have existed more than a million years after we previously thought it had died out.

The find will have the effect of making us rethink our evolutionary history. It shows that, rather than bipedalism arriving as a package that largely resembles our own locomotor form, there was, in fact, a great deal of variety in the past in this the quintessential hominin character.

Yet again, the hominin record has thrown up a big surprise, shifted us from our intellectual comfort zones and forced us to reconsider our long-held assumptions.