It is humbling to think that a disease once responsible for the paralysis of many thousands of children each year is now safely contained within the realm of period drama.

This week sees the release of Breathe, the directorial debut of Andy Serkis. The film charts the remarkable true story of British disability rights activist Robin Cavendish – sensitively portrayed by actor Andrew Garfield – who pioneered technologies to promote the independence of the paralysed after being struck down by polio himself in 1958.

Polio is a highly contagious virus that is typically transmitted by person-to-person contact, or via exposure to contaminated food or water. Most individuals exhibit no symptoms or a few days of flu-like illness. But roughly once in every 200 infections, the virus spreads from the gut to the central nervous system, where the destruction of nerve cells gives rise to paralysis. In these cases, the prognosis varies widely. Although there is no cure for polio, some individuals recover fully with supportive treatment. Others are less fortunate, suffering permanent disability or death.

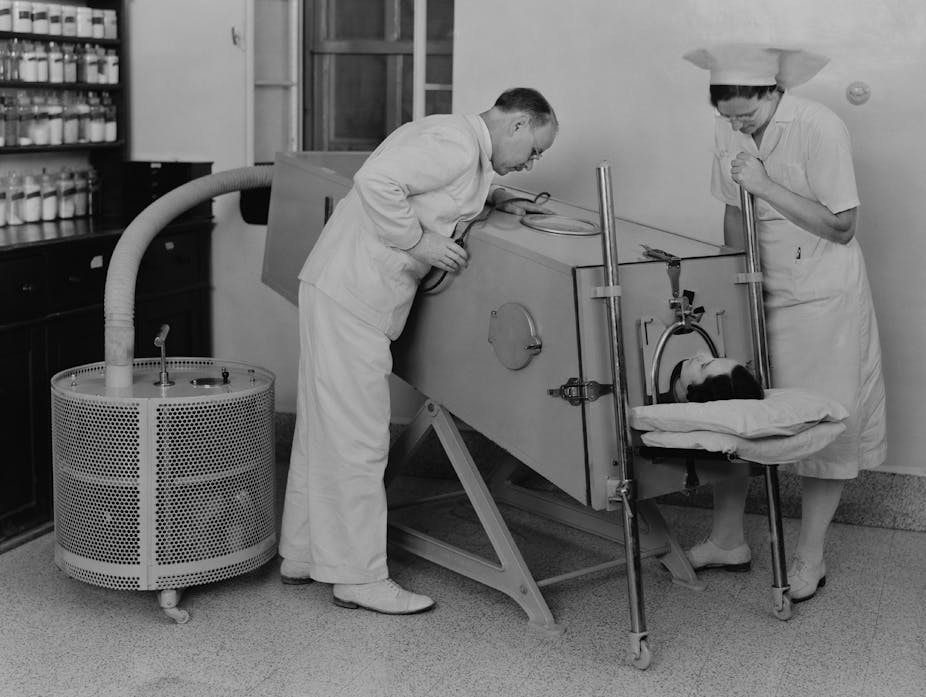

Breathe is in turns funny, inspiring and deeply moving. But it is the devastating effects of polio that linger longest once the end credits have rolled. One moment, Cavendish is an athletic young man whose skills on the tennis court are the envy of his peers. The next, he is paralysed from the neck down, never to walk again. He later visits a ward full of people in iron lungs – coffin-like contraptions that provided artificial respiration for the worst-affected polio victims. “Why do you keep your disabled people in prison?” is Cavendish’s blunt response. It is a haunting scene.

How polio paralysed the world

At its height in the 1940s and 1950s, polio was a terrible blight on society. People lived in fear of the annual summer epidemics of paralysis, which predominantly affected children. The sight of hospital wards lined with iron lungs was commonplace. One particularly severe epidemic in 1947 caused more than 7,000 cases of paralysis and more than 600 deaths in England and Wales alone.

The tide eventually turned after the development of two effective polio vaccines: one injected and one oral. Since their introduction in the 1950s and 1960s, progress to extinguish polio has been steady but sure. The Americas were certified polio-free in 1994, and Europe followed in 2002. As recently as the early 1990s, polio caused between 500 and 1,000 cases each day in India, but the country has been free of polio since 2011.

Though polio has not been totally eradicated globally, the world is on the brink of one of the great landmarks in medical history. The disease is at present largely restricted to Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Nigeria – and 2017 is on track for a record low, with just 12 cases of paralysis due to wild poliovirus so far.

With each year that passes, the fear that once surrounded polio subsides. It is hard to truly appreciate the sense of dread that accompanied the first cases of an epidemic – or the anxiety of a parent hoping to shelter their child from an invisible viral menace.

Eradicating viruses

Other diseases have followed a similar fate to polio thanks to vaccinations. Rubella – also known as German measles – is a virus capable of causing miscarriage, stillbirth, or severe birth impairments when it infects pregnant women. Before a vaccine was available, 200-300 infants with congenital rubella syndrome were born in the UK each year. Since the introduction of the MMR vaccine in 1988, rubella has become extremely rare – there have been just eight confirmed in the UK since 2013, for instance.

More examples abound. In addition to polio and rubella, routine vaccination currently protects children against diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, Hib disease (Haemophilus influenzae type B), rotavirus, measles and mumps. All are potentially life-threatening illnesses that have dwindled at the hand of effective vaccination.

But vaccines can be a victim of their own success. When the emotional threat of a disease is lost, vaccination can feel more like a lifestyle choice than a life-saving precaution. Such complacency is severely misplaced. Vaccine-preventable diseases are tenacious beasts, adept at reigniting if immunisation rates drop.

The resurgence of measles in the UK following the MMR vaccine scare is testament to this – in 2016 the disease caused more than 500 cases in England and Wales. Recent news that the UK has crossed the WHO target of immunising at least 95% of children with at least one MMR dose by their fifth birthday is long overdue.

Any sense of safety is also a privilege of geography. While vaccine-preventable diseases may have dwindled in the UK, many continue to plague the poorest regions of the world. The WHO estimates that more than 100,000 infants are born with congenital rubella syndrome each year. And, as recently as 2015, measles caused an estimated 134,200 deaths globally – one every four minutes.

Breathe offers a timely reminder that the diseases we vaccinate against have the potential to devastate lives. When we take vaccination for granted, we do so at our peril.