The patent wars took a bizarre turn this week.

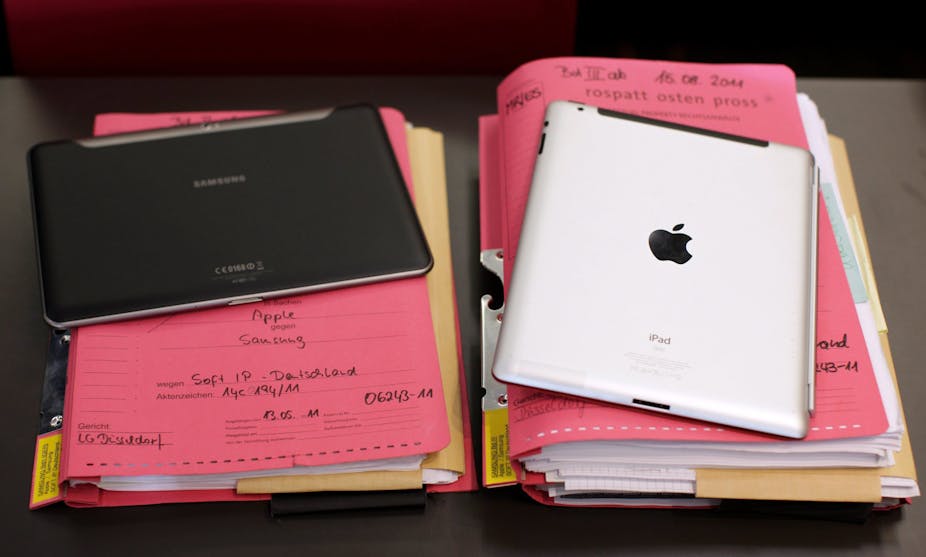

Samsung, currently defending itself against a legal move by Apple to have four Samsung smartphones and tablets banned from America due to alleged patent infringement, pointed to tablet-style computers in Stanley Kubrick’s classic 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Samsung claims the 1968 Kubrick version is an example of “prior art”, a forerunner to the tablets of today. See the embedded video clip below and make up your own mind.

The move comes hot on the heels of headlines charting the enormous recent activity in patent acquisitions and patent infringement proceedings in the mobile telecommunications arena.

“Nortel patents sold for $4.5bn”, we read one day; “Apple sues HTC for infringing on 20 iPhone patents”, the next.

So why is all of this happening? Is it a new phenomenon? And perhaps most importantly, what are the implications for consumers?

Some experts – including those at the risk management corporation RPX – take the view that there are more than 250,000 patents relevant to smartphones. Others are of the view that 250,000 is a gross underestimation.

Whatever the actual number, one can confidently say it’s “large”. “Large” is also likely to be the case in relation to the number of patents relevant to other types of mobile products such as tablets.

Engaging with the enemy

One significant consequence of current proceedings is that participants in the mobile products market will need to obtain patent licences from their competitors in order to have the freedom to conduct their mobile products businesses.

This results in significant cross-licensing deals between competitors – such as the agreement between Research in Motion and Motorola – which in turn can result in significant royalty streams to those with the patents from those without those patents.

Therefore, for those companies without the patents, they will either try to develop their own – a long-term process – or acquire patents from others.

With a larger number of patents in their portfolio, companies are much more likely to find patents their competitors infringe – in other words, there’s a greater likelihood competitors will fall within the ambit of relevant patent claims.

This provides better leverage in any cross-licensing deal and rebalances the royalty flow.

This was the case in the abovementioned Google acquisition of Motorola Mobility – and hence the competitors of Google trying to stymie Google by acquiring the Nortel patents.

In particular circumstances that rebalance may ultimately create what in the Cold War was referred to as mutually assured destruction (MAD) – i.e. if protagonists know they each have serious patent firepower it will stave off a litigation apocalypse.

For those with the patents, if they cannot obtain the royalties they want, they will enforce their rights through patent infringement suits. Hence the recent spate of smartphone- and tablet-related patent litigation.

The game remains the same

All this has happened before in the context of competition for new and valuable markets. Take the case of the US computer memory and semiconductor manufacturer Micron.

The company’s 1994 Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filing referred to owning only 557 US patents and having paid $251 million in royalties for the fiscal years 1992, 1993, and 1994.

Micron’s 2010 SEC filing referred to owning 16,800 US patents and 2,900 foreign patents.

That same document contains a reference to a cross-licensing deal between Micron and Samsung under which the former will receive $275 million in royalties – a clear rebalancing for Micron.

Where you fit in

The implications for consumers can be considered from at least two perspectives:

1) the cost of the above products to consumers 2) the extent to which innovation will continue in relation to these products.

While the cost of any patent-related activities mentioned above would need to be recouped, that does not necessarily lead to higher prices where the market for relevant products is growing.

History also points to lower prices as the technology evolves over time.

On the innovation front, while in some instances the entry of new products has been delayed through court proceedings, innovation in mobile telecommunications continues apace.

Also, new entrants to market have been a feature of the market. One striking example is the fact that, notwithstanding Motorola was a leader in mobile phone technology and held significant patents in that space, it nevertheless did not sustain that early advantage.

This is because it failed to pick up other trends early enough – for example, the move from analogue to digital, cameras in phones etcetera. What happened? Others entered the market.

So should we panic? Definitely not. To date, it’s hard to see consumers as casualties of the patent wars.