Just when we all thought that the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) had already won the race to be most ineffective regulator of the year, up pops the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority with a late run for the flag.

This week, APRA has published an “information paper” on risk culture which is so banal that it really should be filed under anaesthetic rather than analysis.

Risk culture is a notoriously difficult and ill-understood topic but first, why is APRA even talking about this subject – surely culture is the role of ASIC?

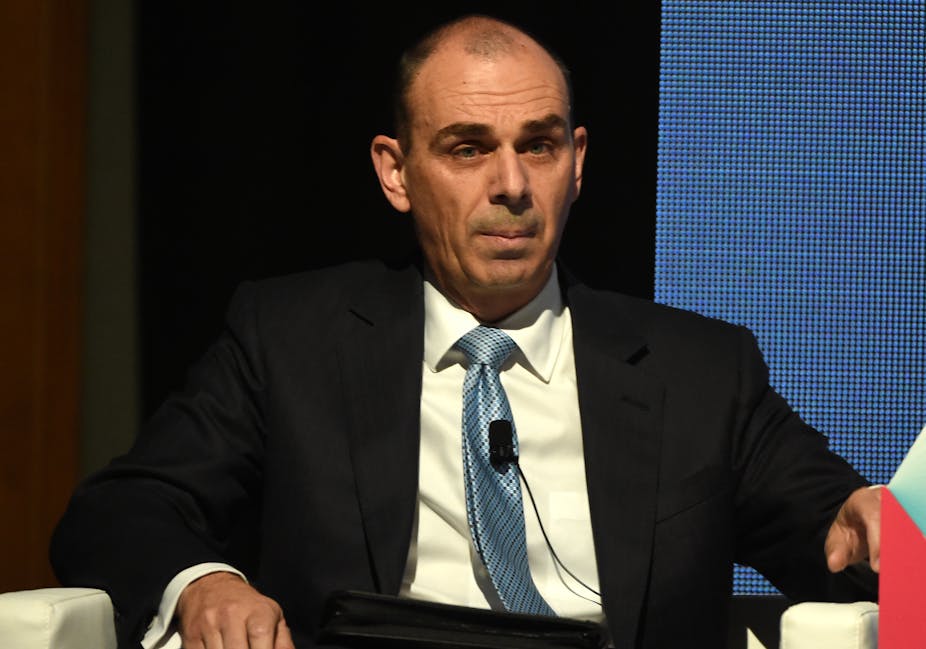

Indeed, ASIC are making noises about culture in the industry, with the chairman lately requesting even more powers to lock bad people up.

“If you’re a law enforcement agency you’ve got to have penalties that actually hurt.”

In fact, APRA does make a case why, as prudential regulator, it should consider risk culture:

“APRA’s focus on risk culture reflects its prudential mandate - that as a result of undesirable behaviours and attitudes towards risk-taking and risk management, the viability of an APRA-regulated financial institution itself might be threatened, and this may in turn jeopardise both the institution’s financial obligations to depositors, policyholders or fund members, and financial stability”.

While ASIC’s primary focus is on illegal actions by individuals (and arguably corporations), APRA’s mandate is to consider risks to the whole banking system. However having made the argument, APRA promptly forgets its systemic role and starts dabbling in the same mess that ASIC is trying to clean up, without much success.

This approach stems partly from intellectual laziness.

Culture is a very complex, abstruse area of academic research. In the field of ‘organisational culture’, Edgar Schein is seen as a leading light.

He has been active in the field since the late 1990s and has produced a definition of culture, which has stood the test of time and is at least referred to by academics and researchers in the field. Rather than choose to at least consider (and if necessary reject) Schein’s definition of culture, APRA has chosen a much more specific definition from the early 1990s without explanation.

This is not an obscure academic point, since Schein’s definition encompasses the very area that APRA claims to be interested in, what is called “macro-culture”, or culture that pervades an industry or sector. APRA notes that there were problems common across the financial industry but does not address why these might occur, other than as a consequence of competition:

“More recently, APRA highlighted the emergence of increased risk-taking within the life insurance industry with respect to the underwriting and pricing of, in particular, group insurance business. At its heart, this stemmed from a focus on growth without, in a number of institutions, adequate regard to the risks that came with it.”

Schein’s definition also covers different cultures in different parts of organizations, or so-called “sub-cultures”. It’s interesting that APRA found evidence of sub-cultures in its discussions with banks but did not follow up the obvious connotations for its work:

“Larger institutions noted that size and complexity introduced additional challenges, particularly regarding the greater prevalence of sub-cultures. In these instances, efforts were segmented, often by geography or business unit.”

Rather than tackle the complex issues within firms that have an impact across the industry, APRA has fallen back on the old staple – ask the banks themselves what they are doing and then promote some sort of vague best practice.

However, the APRA report shows that the banks are as lost as APRA, with varying definitions and vague ideas as to how abberant culture may be addressed. APRA also provided some information about what other regulators are doing in this area but have not decided to follow their leads preferring to do some “pilot risk culture reviews” at selected banks.

In other words, APRA will turn up to the same banks (yet again) and ask mainly the same questions. But is there a better way?

Australia is a leader in the field of ‘risk culture’ research. In a project funded by the Centre for International Financial Regulation (CIFR), Professors Elizabeth Sheedy and Barbra Griffin from Macquarie University, have researched risk culture on the ground by surveying over 30,000 staff in over 270 business units in seven large Australian and Canadian banks.

From that research, they have developed a scale that allows comparison between business units and banks as regards their staff’s perception of risk in their organisation.

Why has APRA not picked up this research, at least as a starting point for their pilots? Alternatively, if they have considered and rejected the results of the studies, why have they not reported their reasons?

Possibly because the answers (and further research questions) thrown up by Sheedy and Griffin’s research are uncomfortable for APRA to read.

The research shows that, contrary to the regulatory mantra of “tone from the top” repeated incessantly by APRA, risk culture is business unit specific. Even two units in the same business line sometimes having different perceptions of risk.

Professor Sheedy summarised the findings:

“Culture is very much at a local level. You often hear people talk about this theory of one bad apple. I’m very sceptical of that notion. I don’t buy it …I think what happens is that the culture develops in such a way that that sort of behaviour becomes acceptable.”

Furthermore, as anyone who followed the recent questioning of bank CEOs by the House Economics Committee would have concluded, senior managers have a much rosier perception about what is actually happening on the ground than their staff and customers.

On the other hand, bank staff would have definitely got the message from the responses of all of the CEOs to the committee’s questioning - apologise profusely, don’t sack anyone and protect your bonuses. The CEOs’ actions say a lot more than the pious behaviour guides being developed by some banks as reported by APRA.

It appears that APRA just wants a quiet time, kicking the can down the road by doing some more talking without a rigorous framework for action.

In 2015, the Abbott Government established an expert panel to review the capabilities of ASIC, the results of which were published by Minster Kelly O’ Dwyer in April 2016. It was uncomfortable reading, with ASIC being revealed as a dysfunctional, over-worked and under-resourced organisation.

Kicking yet another can down the road until after the imminent election, the government gave ASIC back the funding that it had removed the year before, extended the chairman’s tenure by 18 months and announced an additional commissioner to prosecute financial crime. The new commissioner has yet to be appointed.

Maybe it is time for a similar capability review of APRA, since they appear to have lost their way, opting for a quiet time rather than pro-active regulation?