An aquatic lizard twice the length of a Komodo dragon once lurked in rivers during the age of dinosaurs, according to a team of Hungarian-Canadian researchers.

The 85 million-year-old Pannoniasaurus is the first known example of a freshwater mosasaur, a group of giant, extinct sea-going lizards.

The reptile was named after the Hungarian region of Pannonia where it was found – which, during the Cretaceous Period, was a vast tropical river plain, probably resembling today’s Amazon region.

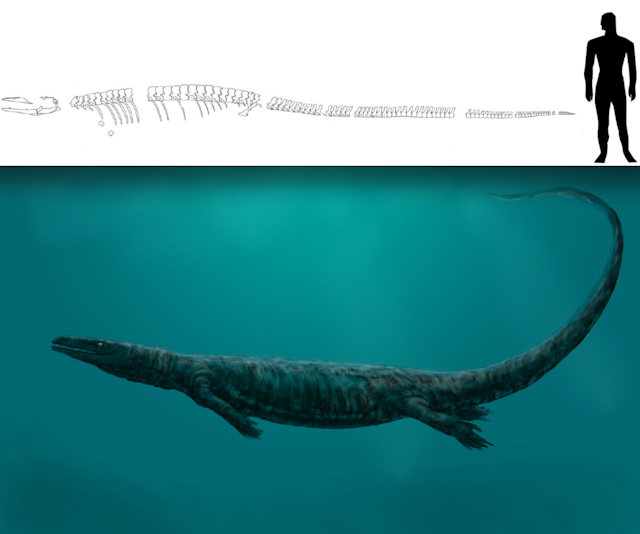

The six-metre lizard had a flattened, crocodile-like skull and was presumably a shallow-water ambush predator, potentially preying on frogs, terrapins, freshwater fish and small dinosaurs, all of which are preserved as fossils in the area.

Mosasaurs are undoubtedly the most spectacular lizards ever to have existed. Like cetaceans (whales and dolphins), they evolved from four-legged, terrestrial ancestors into fish-shaped aquatic forms.

With their weight now supported by water, and live birth removing the need to ever wade ashore to lay eggs, the largest mosasaurs grew as long as sperm whales (stretching over 15 metres).

Until now, all mosasaurs have been found in marine rocks, but the new Hungarian find demonstrates they also inhabited freshwater ecosystems. More than 200 bones from multiple individuals ranging from juveniles and adults suggest a permanent population, rather than an occasional migrant.

In their new paper in the open-access scientific journal PLOS ONE, Laszlo Makadi and colleagues gave the newly discovered species the full name Pannoniasaurus inexpectus, having been surprised by the mosasaur’s freshwater habitat. But considering the close parallels between mosasaur and cetacean evolution, such a freshwater mosasaur was hardly unexpected: many cetaceans have invaded freshwater ecosystems, refining their sonar and losing their eyesight and body colour due to the murkier river waters.

These river dolphins represent multiple cases of convergent evolution, and are now sadly among the most critically endangered creatures today.

Pannoniasaurus is also intriguing because it represents a transitional form, helping reveal how small land-dwelling lizards evolved into enormous sea monsters such as Hainosaurus. Pannoniasaurus could function both on both land and in water, retaining weight-bearing girdles with short stubby legs for walking, but possessing a paddle-like tail for swimming, and nostrils near the top of its head for breathing while submerged.

Several other creatures broadly similar to Pannoniasaurus are known, such as the smaller Aigialosaurus, but all these are from marine deposits: they presumably inhabited ancient mangrove-like habitats. These amphibious lizards eventually evolved into giant ocean-going mosasaurs, with full marine adaptations such as flippers probably arising twice.

As well as revealing how land vertebrates can re-invade the oceans, mosasaurs help shed light on several other major evolutionary topics. Their highly flexible skulls and jaws, which allow them to swallow large prey, resemble those of monitor lizards (goannas) and snakes. Mosasaurs might be closely related to either or both groups.

Recent work based on high-resolution CT scanning documents these similarities, but concludes these feeding adaptions probably represent yet more instances of convergent evolution.

Their spectacular appearance and evolutionary importance means mosasaurs are the most heavily studied and well-known group of fossil lizards. But the discovery of Pannoniasaurus inexpectus suggests that major new discoveries are still likely.