Where the Limpopo and Shashe Rivers meet, forming the modern border between Botswana, South Africa and Zimbabwe, lies a hill that hardly stands out from the rest. One could easily pass it without realising its historical significance. It was on and around this hill that what appears to be southern Africa’s earliest state-level society and urban city, Mapungubwe, appeared around 800 years ago.

After nearly a century of research, we’ve learnt quite a lot about this ancient kingdom and how it arose among early farmer society and its involvement in global trade networks. However, before farmers settled the region, this terrain was the home of hunter-gatherer groups, who have hardly been acknowledged despite, as it seems, their involvement in the rise of Mapungubwe.

My team and I have been working in northern South Africa at sites that we believe will help us recognise the roles played by hunter-gatherers during the development of the Mapungubwe state in a bid to generate a more inclusive representation of the region’s past.

Our primary study site is called Little Muck Shelter. It is in the Mapungubwe National Park and about 4km south of the Limpopo River. The shelter is fairly large with a protected area under a high ceiling and a large open space in front. It also has many paintings on its walls, including elephants, kudu, felines, people, and a stunning set of giraffes. This art was produced by hunter-gatherers and it is generally considered to refer to the spirit-world and the activities of shamans therein.

The results from our research shows two things. First, hunter-gatherers lived in the area while the Mapungubwe Kingdom arose. Second, during this time they were part of the economy that assisted with the appearance of elite groups in society, and they had access to this wealth. When combined this tells us that we cannot think about Mapungubwe’s history without including hunter-gatherer societies. They were present and a part of these significant developments.

Why is this important? One of the foundational developments that took place that led to the rise of the Mapungubwe Kingdom was the accumulation of wealth. It drove the appearance of hierarchies in society and marked prestige. These trade goods were valuable items usually possessed by elite groups. And yet, hunter-gatherers, through exploiting their own skills, were able to obtain related goods at a time when these items were contributing to significant transformations in society. That they had access to wealth during this period likely shows us that their role in local society was valued and they were entrenched in the local economy in a way that we’ve not previous recognised.

Read more: Rock art as African history: what religious images say about identity, survival and change

Unearthing evidence of trade

We were attracted to Little Muck Shelter because of previous work at the site in the late 1990s that showed intense trade between hunter-gatherers and farmers took place from the shelter. To understand this better, we needed a larger archaeological assemblage to verify, or refine, what we thought might be taking place.

We also wanted to more closely examine the depths that dated between AD 900 and 1300, during which the processes leading to Mapungubwe began and ultimately concluded, in order to clearly show a hunter-gatherer presence during this period as well as their participation in local economic networks.

To do this, we needed to dig. Archaeological excavations are a slow and meticulous process that involve the careful removal of layers of artefact-bearing deposits with a very strict control of depth and location within an excavation trench.

Following this is a lengthy period of analysis that adheres to rigorous protocols to ensure consistency in identifying artefact types, their production techniques or methods, how they were used, and what they were made from.

We then piece all this evidence together in our attempt to understand past ways of living. From our results, we were able to trace a hunter-gatherer history that intertwined with the rise of Mapungubwe.

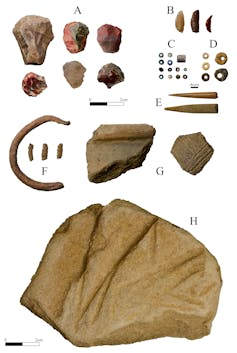

Our first and important task was to show that hunter-gatherers were still around when Mapungubwe appeared. To date, we’ve examined about 15,000 stone tools from a sample of our excavations and identified a set of finished tools that are the same as those produced by hunter-gatherers for millennia before farmer groups appeared. We believe that this consistency in cultural material over such a long span of time clearly shows that hunter-gatherers were living in the shelter when farmers were in the area.

We then wanted to look more closely at the trading economy. From the moment farmer groups appeared in the region, during the early first millennium AD, hunter-gatherers shifted their craft activities. Rather than mostly producing goods made from hide, wood and shell, they began making mostly bone implements and did so until the end of the Mapungubwe Kingdom at AD 1300. This suggests that the interactions hunter-gatherers had with farmers from when they first arrived stimulated change in their crafted wares.

Why did they change their crafting activities? At the same time that these shifts took place, we recorded the appearance of trade wealth in the form of ceramics and glass beads, initially, and then metal. These goods were never made by hunter-gatherers and are common at farmer settlements, indicating exchange between these two communities. It indicates that hunter-gatherers responded to new market opportunities through emphasising their own skill sets.

Our work to identify more evidence that shows a hunter-gatherer involvement in these processes continues. We are trying to find out in what other ways they were involved and whether they themselves developed a more complex society.