In August 2021, the world was gripped by images beamed from Afghanistan when the Taliban entered Kabul. Terrified Afghans ran for their lives to the airport. People were clinging to the wings of aircraft and holding babies over barbed wire, hoping they would be taken to freedom. Thousands braved the crush outside, as the last of the international planes departed. For months afterwards, tens of thousands more fled overland to neighbouring Pakistan and Iran.

When war broke out in Ukraine, international attention waned. The Taliban consolidated its control across Afghanistan. The Islamic fundamentalists increasingly cracked down on women’s rights, in particular.

Afghanistan has now reopened a nascent tourism industry. Some people have even reported an increase in security in the country. But if you are a woman, or are from an ethnic minority, or wish to claim some basic human rights, you will most definitely not experience security.

The Taliban continues to disappear and imprison human rights defenders, including those who advocate for the rights of women and ethnic minorities. Law and justice continue to regress to the dark ages. The Afghan economy is in dire straits.

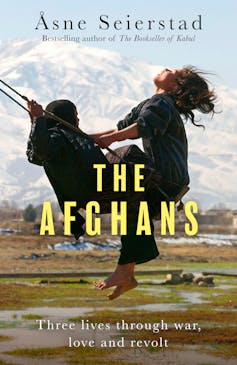

Review: The Afghans: Three Lives Through War, Love and Revolt – Åsne Seierstad (Hachette)

Norwegian journalist Åsne Seierstad is the author of several non-fiction books set in places that have been wracked by conflict. Her interest in violent extremism has taken her all over the world. She has written books about Syria, Iraq, Chechnya and Serbia, as well as a biography of the Norwegian extremist and mass-murderer Anders Breivik.

Seierstad’s first book and best-known work, The Bookseller of Kabul – an international bestseller – was set in Afghanistan. She is familiar with the country and its people. But she was just as shocked as the rest of the world by the images of the Taliban retaking Kabul. She realised how much she had not been paying attention to events in Afghanistan over the 20 years since her first book.

When she was asked to comment on the situation, Seierstad decided to go back, follow up with some of her old connections, make some new acquaintances, and tell a story of life under the Taliban in Afghanistan today.

The resulting book, The Afghans, is an intimate work that follows the lives of three disparate individuals. Jamila is a powerful women’s rights activist who lives with a physical disability. Bashir is a high-level Taliban leader raised by a strict Pashtun widow. Ariana is one of “the young women who thought they could achieve anything, if only they they were smart and worked hard enough, and then everything was taken from them”.

Seierstad has a remarkable ability to sketch out the bigger picture. She provides the relevant historical and geopolitical context, while capturing the texture and detail needed to convey the character of everyday life in Afghanistan. She identifies the barriers to peace, prosperity, equality, freedom and justice, and unpacks the intersectional dimensions of the problems, weaving in complex and revealing details about gender, disability, ethnicity, education and economic markers that affect social mobility.

This makes The Afghans both powerful and endearing. It helps to build a personal connection with the characters, in all their flaws. Seierstad, for example, recounts the moving story of how Jamila’s parents did not believe in doctors, so Jamila was never vaccinated for polio. When she began to exhibit neurological symptoms when she was young, her parents believed it was the result of devilry or sorcery and had shamans visit her.

The polio that had infected her left Jamila with a disability. Afghan girls are not supposed to want things, so when she tried to teach herself to walk with her one good leg, her parents discouraged her. Eventually, when Jamila taught herself to walk, dragging her bad leg behind her, the other kids jeered at her. Jamila’s brothers were so ashamed of her disability that they would run off without her and do nothing to assist or defend her from bullies.

Unique insights

Seierstad’s three subjects were born a decade or two apart: Jamila in the 1970s, Bashir the 1980s, and Ariana the 2000s.

Collectively, the stories of their youths cover the recent history of Afghanistan. They reveal how the Taliban first came to power in 1996 at the conclusion of the Afghan Civil War of 1992–96, and how, after 20 years of Western intervention in Afghanistan following the terrorist attacks of September 11 2001, they managed to return to power again.

The book does not shy away from the everyday experience of violence, or the disparity between rural and urban development. During the Taliban’s previous reign, Seierstad observes:

Maternal mortality was sky high. Infant mortality was the highest in the world. Every fourth child died before the age of five. Life expectancy was little over forty years of age. The infrastructure was in ruins; scarcely a waterpipe lay unbroken. Millions of landmines made it hazardous to move around, let alone to clear the fields the war had laid fallow.

Afghan women fought hard for their rights. According to the Afghan Women’s Network, during the 20-year international intervention, the maternal mortality rate dropped to 460 per 100,000 women. Women’s civic groups spread across the country, advocating women’s rights, organising and training women to take part in business and in politics, holding the government and international donors accountable – both collectively and independently.

Now the Taliban has returned to power, the situation has reversed. The UN Population Fund reports that in Afghanistan today “childbirth can, in effect, be a death sentence”.

The Afghans provides a unique insight into how the Taliban retook control of Afghanistan by describing the personal experiences of Bashir, now a senior Taliban leader. The book follows his career and some of his key battles, but also describes his family life and personal challenges.

As a boy, before September 11 2001, Bashir ran away from home. He trained in the camp of guerilla leader Jalaluddin Haqqani. The Haqqani Network would become one of the most extreme militant groups in the country. Now run by Jalaluddin’s son, the Haqqani Network was given control of the Ministry of Interior and the geographic area of Kabul when the Taliban returned to power.

In December 2001, in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, negotiations in Bonn, Germany, sought to devise a plan for the administration of Afghanistan. The Bonn Agreement involved an array of Western diplomats, as well as representatives from Pakistan, Iran, India, Russia and neighbouring Central Asian countries. But, as Seierstad drily notes, the agreement had “one weakness everyone seemed to overlook. The Taliban weren’t invited.”

Twenty years later, negotiations at the Doha peace talks of 2021 had the opposite problem. After relying on the manpower – literally, the lives and deaths of people from their NATO allies – and billions of dollars in aid money to fight their war in Afghanistan, the US excluded anyone except the Taliban from withdrawal negotiations, including the democratically elected Afghan government.

The passages in The Afghans about the Doha peace talks and civil society negotiations are particularly moving. Seierstad adroitly narrates the dynamics between the presidents and secretaries, ambassadors and negotiators, and their Afghan counterparts. She describes a poignant moment when one participant pleads:

Please, for God’s sake, the Taliban are not in favour of negotiations, they are not in favour of political settlement. They’re on a victory march!

In part three of The Afghans, Seierstad gives a gripping account of how the Taliban retook control of Afghanistan following the withdrawal of US forces in May 2021, seizing one province after another. “Bit by bit,” she writes, “the republic was becoming an emirate.”

The story of Ariana, the youngest of Seierstad’s three subjects, illustrates just what is at stake in the struggle between Bashir, as a representative of the Taliban, and Jamila, as an Islamic feminist, who was an assistant minister in Afghanistan before she was forced into exile. A student when the Taliban returned to power, Ariana had much to lose as a result of the suppression of women’s rights. Initially, she could not even believe the Taliban could have taken Kabul:

Her sister Zohal could never do without Turkish soap operas, and it was hard to imagine life without Netflix and Justin Beiber. […] No, it was impossible, nobody wanted the Taliban here in Kabul. The entire population would revolt against them. People would gather in the streets to protest.

Afghans did gather in the streets of Kabul and protest. But the Taliban beat them and arrested them. When local journalists reported on the protests, they too were beaten, arrested or disappeared.

After a while, most international media left Afghanistan. Those that remain have negotiated a fragile truce with the Taliban to maintain their presence and security. Visas for Afghan refugees needing to flee have slowed to a trickle.

Governments have turned their backs on these people. But after 20 years of military deployments and international aid interventions, there are many people around the world who feel invested in the lives of the ordinary people of Afghanistan and care deeply about their welfare. For them, Seierstad’s book will be a timely lifeline to the place and its people. For other interested readers, it provides a powerful account of the country’s troubled recent history and the personal struggles of its people. The Afghans deserves to be as much of a success as The Bookseller of Kabul.