As with a lot of business, gambling has become globalised. Australian investors and governments over history have courted high rollers – VIP clients ready to spend very large amounts of money on the gaming tables of luxury casinos. From being the bogeyman of Australian racial imagination in the late 19th century, the Chinese gambler became the hope of the Australian investor in the early 21st.

The arrest of 18 Crown employees in China is a reminder that the risks associated with this industry are not only taken by the high rollers at their VIP tables.

The Chinese VIP

A decade ago researchers on Chinese gambling in the Asia Pacific noted that outbound tourists from China were headed mainly to Las Vegas or Australia. But ageing Australian facilities were already facing increasing competition, not only domestically, but from new challengers in Asia.

Over the following decade Macau became a premier destination in terms of gambling visitor numbers as well as revenue - at its height in 2014 the revenue was reported to be more than seven times that of Las Vegas.

In that year Macau received at least 28 million visitors and upgraded its border management processes to accommodate a daily flow of approximately 500,000 visitors. But as the Chinese government began to crack down on corruption and money laundering, the fortunes even of the Macau casinos have slowed.

Participants in that great Australian past-time, tracking the fate and fortunes of the Packer family, know of some of these recent changes. James Packer’s publicly listed company, Crown, some time ago embarked on a mission to create Sydney as a destination of choice for Chinese high rollers. He was competing with other major Pacific rim gambling enterprises in Singapore, the Philippines and of course Las Vegas, as well as Macau and Hong Kong.

Crown has recognised the Chinese VIP customer wants a six star resort hotel. So building one on Australia’s best harbour and beside the iconic bridge is Crown’s aim. The Barangaroo complex, a mix of residential and casino offerings, remembers in its name a powerful female Aboriginal woman, a wife of Bennelong.

Neither Crown nor Sydney play in this field alone of course. Indeed Crown’s ambition flows in part from its success in Melbourne where it boasts of being Victoria’s largest single site private sector employer. This is an astonishing testament to the changes that have taken place in the economy and labour market in Australia since the 1980s.

High rollers are not the only Chinese visitors to spend money gambling in Australia. A survey from Tourism Australia suggests Chinese visitors who come here to gamble spend much more doing so than visitors from anywhere else – although the volume of their spending does not yet exceed the vast pool of international student income that funds our universities.

Changing attitude to the Chinese gambler

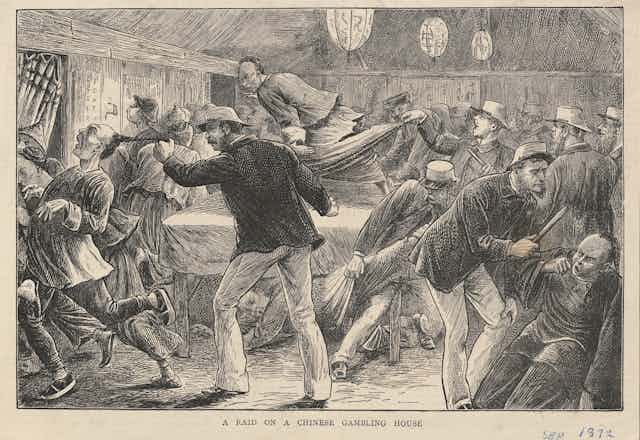

No mention is made on Crown’s Barangaroo website of an earlier history of Chinese gambling on the other side of the Miller’s Point Peninsula in Sydney. But more than a century ago a Royal Commission in NSW investigated alleged Chinese gambling and immorality and associated bribery of police in the Rocks and surrounds.

Witnesses testified to a very active Chinese gambling industry, operated through street-front shops which sold the tickets for pak-ah-pu (a kind of lottery) and in back rooms where fan-tan (a Chinese gambling game) was played and large amounts of money appeared to change hands.

Evidence suggested that some of the gaming delivered money into the hands of the fraternal associations that helped Chinese living in Australia. These associations arranged funeral services, returning bones to China, and supported the surviving family members.

Gambling revenue also funded the often successful legal defence of those prosecuted by colonial police. One of them was successful on appeal to the NSW Supreme Court in 1881 against a gaming conviction for running a game of pak-ah-pu.

As a story of colonial Australia, the prosecution of Chinese gamblers may be something of a picture of the experience of Chinese more generally at that time. It was a symptom of sometimes aggressive policing, but equally a means of provoking an assertion of legal rights in the face of that policing.

Through such legal actions Chinese gamblers asserted their entitlements, and their capacity to gather resources, financial and personal and community, in their own defence.

The return of the Chinese gambler

In October 2013 James Packer joined champion tennis player Li Na in Beijing to announce the renewal of his company’s sponsorship of her tennis venture. It was another gamble that paid off handsomely when Li Na won the Australian Open just a few months later.

This relationship was not just a sporting moment, but a passage in Chinese-Australian relations. In Beijing, Packer welcomed the accolade accorded his enterprise in the Gillard government’s White Paper on “Australia in the Asian Century”. Crown had been singled out for its vision:

“The tourism industry needs to develop culturally relevant products to capitalise on growing Asian interest in Australia as a tourist destination. This will mean developing sophisticated luxury urban tourism opportunities, such as those offered by Crown Limited, as well as showcasing Australia’s outstanding natural beauty.”

Contemporary Australian governments and leading companies are increasingly courting Chinese gamblers – they do so in an increasingly competitive global gambling environment. Crown’s case reminds us this is not without risks.