Finally, the AFL home and away season is beginning. Once again our footy teams will make history.

But let us not forget that history made footy.

Australia, notes Geoffrey Blainey in his Shorter History of Australia, was possibly “the first country in the world to give a high emphasis on spectator sports”. And of course, one important spectator sport was Australian Rules Football.

The wisdom of the crowd

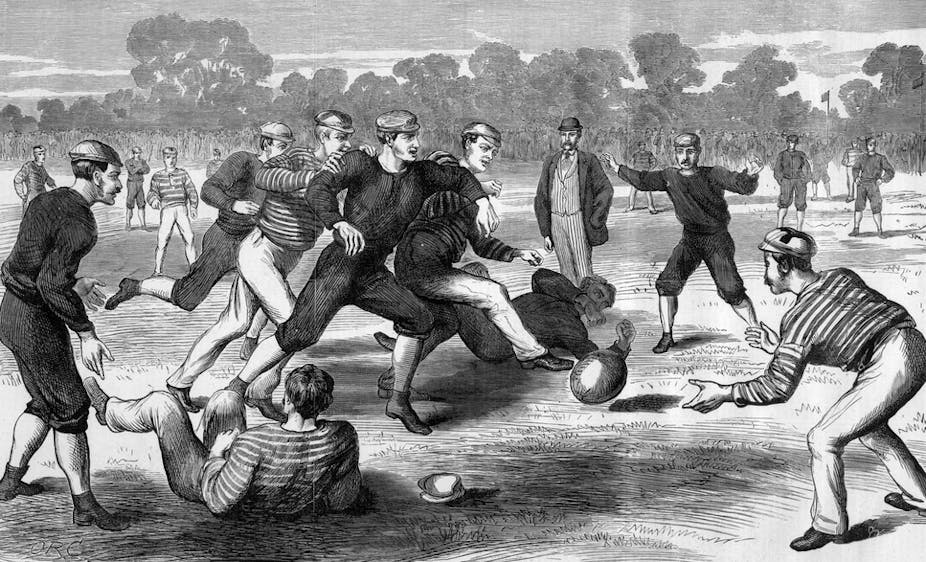

Formed in 1859, Melbourne and Geelong are among the world’s oldest football clubs. They were soon followed by Carlton (1864) and North Melbourne (1869). More teams were created in the 1870s; including Essendon (1871), St Kilda (1873), and Hawthorn (1873). By this stage, football clubs had also formed in other parts of Victoria and Australia, including Adelaide, Port Adelaide and Woodville, New South Wales. However, it is generally accepted that some clubs of this period may have only tenuous connections with the current clubs of the same name.

Huge crowds soon attended games in Melbourne. In 1880, big matches might attract crowds of 15,000. In 1886 a South Melbourne v Geelong game attracted 34,000, “possibly the largest football crowd in the world up to that point” according to Blainey.

But it wasn’t just the “big league”. Australian Rules’ early years were as much about participating as spectating. As Burke writes in his PhD thesis, teams were formed around places of work, professional colleagues, “schools, churches, hotels and self-help organisations”.

Accounting for the expansion of the code, the club and the fan was some astonishing and unforeseeable historical changes and coincidences - in Australia and in Europe. Prominent among them was leisure.

The life of labour

Leisure was crucial to the development of Aussie Rules. We take the idea for granted, but leisure as we know it was created in the 1800s, and Victoria played a significant role in the new way of thinking about work and labour.

Before 1500, the majority of Europeans probably viewed work as inescapable, unpleasant, and burdensome. Had not God punished Adam by condemning him and his descendants to lives of toil? Indeed, on this world, but hopefully not the next, they would have to work for a living. By contrast, priests followed a calling, a service to God, ministering to the vulgar laity.

The second way of thinking emerged with the Protestants from the 1500s. According to what is called “Protestant Ethic”, the way to serve God was not through living a life of contemplation in the monastery. Rather, Luther and his followers argued, believers belong to a universal priesthood. Even outwardly turgid and dirty jobs could be one’s “calling”. An ironmonger or cooper could thus be fulfilling a vocation. Such work was infinitely more dignified and pleasing to God than the hated papacy’s peddling superstition and idolatry.

Still, not much solace could be obtained on this world. Many were unsure of whether they lived and worked in a state of grace and would hence be attain salvation.

The fervour with which Protestants worked, and frugality with which they spent, meant many became wealthy in the process. Although they had set out to please God, as famed sociologist Max Weber has said, these Protestants ended up creating modern capitalism.

Thus, until this point two main ways of thinking presented themselves: working to live or living to work.

However, a third way to think to about work, and especially time off work, developed; we could call it “leisure”.

Larrikin leisure

Leisure emerged in unlikely places like Victoria, Australia in the mid-late 1800s.

This is not surprising. Victoria was a social trail-blazer in world history in such notable areas as land reform (an 1860 attempt to limit the squatters’ holdings), democracy (secret ballots in 1856), and labour laws.

In the 1850s, Blainey notes in his Shorter History, “Melbourne saw itself as a world leader of the movement for shorter hours of work”, and well it might.

Its unionism saw stonemasons win, in 1856, the 48 hour week. Other industries soon followed suit and according to labour historian Charles Fahey the eight hour day was pretty general for wage earners by the late 1880s.

The next step was to secure a weekly half-day (the “half-holiday” as it was called) within the 48 hour week. Thanks to unionists and sympathetic employers many began working eight-and-a-half hours for five days and three-and-a-half on one day. By the time this was formalised in the Shops and Factories Act 1896, the “half-holiday” was pretty general. But on which day should the “half-holiday” fall?

The city of Melbourne retail and commercial sector had a Saturday half-holiday. The suburbs by contrast, took the half-holiday on Wednesday, giving rise to a popular Wednesday Football League.

However, by the early 1900s, the Saturday half-holiday became universal.

The miracle of sport

Work and enforced rest had been taken for granted for centuries. Leisure was an innovation. In other words, leaving Saturday afternoon free was a secular miracle. This leisure revolution also created a very new sense of time as composed work and leisure. But what to do with the time created by limited working hours?

Sport was the answer, of course, especially football. As Blainey observes, “The emphasis on leisure became a hallmark of unionism and social life.”

Into the 21st century and the distinction has affected our identity. Nowadays many of us agonise over the “work-life” balance. Some of us think our lives contrast with our work, to the extent we identify with leisure rather than work. We might distinguish “what I do” from “who I am”. This distinction which wouldn’t have made much sense in earlier centuries, much less to an ironmonger named Jack Ironmonger or a cooper named John Cooper.

Now, many of us would identify as much with our football team as with our job or even with God. For better or for worse, it took a historical revolution to get to this point. The footy-crazed Victorians of the 1800s helped make this happen.