Australian teenagers have more disruptive maths classrooms and experience bullying at greater levels than the OECD average, a new report shows.

But in better news, Australian students report high levels of curiosity, which is important for both enjoyment and achievement at school.

The report, by the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) analysed questionnaire responses from more than 13,430 Australian students and 743 principals, to understand how their school experiences impact on maths performance.

What is the research?

This is the second report exploring Australian data from the 2022 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA).

PISA examines how 15-year-old students are able to apply their knowledge in maths, reading and science for real-world problem solving. It is one of three major international tests Australia participates in. Students complete a computer-based test and a questionnaire.

A first report released last December showed Australian students’ performance in maths has not changed significantly over the past seven years. However, when compared to when PISA results were first reported about 20 years ago, there has been a decrease of 37 points.

This new report compares 24 countries out of the 81 countries who did the PISA test. The 24 were chosen because they performed higher or at the same level as Australia in maths.

Are students listening to their teachers?

Students were asked to note how frequently students are not listening to the teacher, there is noise and students are distracted by digital devices. A “disciplinary climate index” was then constructed for each country.

While Japan had the most favourable climate, Australian students’ reported one of the least favourable among the comparison countries. All but two countries (Sweden and New Zealand) had a more favourable disciplinary climate than Australia.

Tasmania and the Northern Territory have the least favourable scores and Victoria and New South Wales had the best. For example, more students in Tasmania than in all other states and territories reported “there is noise and disorder in most classes”.

Being left out and made fun of

The study also created an “exposure to bullying index” by asking students how often certain things happened to them. This included “other students left me out of things on purpose,” “other students made fun of me,” “I was threatened by other students,” as well as acts of physical aggression.

Here, Australian students reported higher exposure to bullying than all comparison countries except Latvia. They also reported similar exposure to bullying as students in New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

Students in Tasmania reported the highest levels of bullying and those in Victoria reported the lowest.

However, the Australian students’ exposure to bullying score decreased between this PISA and the previous test in 2018.

The advantage gap

ACER’s first PISA 2022 report showed students from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds were six times more likely to be low performers in maths than advantaged students.

It also showed the achievement gap between these two groups had grown by 19 points (or about one year of learning) since 2018.

This second report provides more insight into the challenges faced by disadvantaged students.

It shows a greater proportion of this group report learning in a less favourable disciplinary climate, experience lower levels of teacher support and feel less safe at school than their more advantaged peers.

Girls are more worried than boys

In last year’s report, the mean score for maths performance across OECD countries was nine points lower for girls than it was for boys. In Australia, the difference was 12 points.

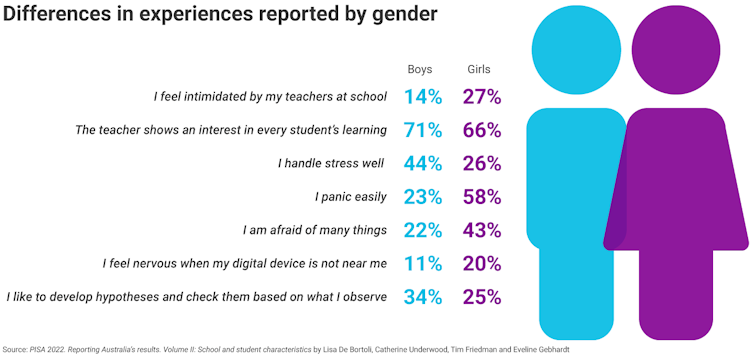

The new report also showed differences in wellbeing. In 2022, a greater number of girls reported they panicked easily (58% compared to 23% of boys), got nervous easily (71% compared to 39%) and felt nervous about approaching exams (75% compared 49%).

Almost double the percentage of girls reported feeling anxious when they didn’t have their “digital device” near them (20% compared to 11%). Whether this was a phone, tablet or computer was not specified.

Overall, students who reported feeling anxious when they did not have their device near them scored 37 points lower on the maths test than those who reported never feeling this way or feeling it “half the time”.

Curiosity a strong marker for performance

Curiosity was measured for the first time in PISA 2022. This included student behaviours such as asking questions, developing hypotheses, knowing how things work, learning new things and boredom.

Students in Singapore, the highest performing country in PISA 2022, showed the greatest levels of curiosity, followed by Korea and Canada. These were the only comparison countries to have a significantly higher curiosity score than Australia, with the Netherlands showing the lowest curiosity score overall.

As ACER researchers note: “curiosity is associated with greater psychological wellbeing” and “leads to more enjoyment and participation in school and higher academic achievement”.

They found Australia’s foreign-born students reported being more curious than Australian-born students, with 74% compared to 66% reporting that they liked learning new things.

What next?

Their findings highlight concerns for Australian education, such as persistently poor outcomes for disadvantaged students and higher stress levels experienced by girls. We need to better understand why this is happening.

But they also identify behaviours and conditions – such as high levels of curiosity – that contribute to a good maths performance and can be used by schools and policymakers to plan for better outcomes.

Correction: an earlier version of this article said 32% of boys surveyed said they panicked easily. This has been changed to 23%.