Following a large group of people over a long time is a terrific way to learn more about life in Australia. The Growing Up in Australia: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) has been going since 2004, following the lives of thousands of children into adulthood and gathering data from parents, teachers, carers and the children themselves.

The latest LSAC Annual Statistical Report provides a window into how the lives of Australian teenagers are changing.

Many have tried alcohol, but few drink regularly

Just over 40% of teens reported having had a few sips of alcohol by the age of 15, but only 16% had consumed a full serve. Of those who had tried alcohol, 28% of boys and 15% of girls had done so before the age of 13.

This doesn’t mean that young teenagers who have tried alcohol are necessarily drinking to excess, just that they are sampling alcohol at a relatively young age. For most 14- and 15-year-olds, drinking alcohol was not a regular practice — only 7% had consumed an alcoholic drink in the month before their interview.

Parents’ regular, short-term, risky drinking was shown to be a strong factor in influencing their teenage children to try alcohol. Around 11% of mothers and 30% of fathers reported having at least five drinks on a single occasion at least twice a month.

Most parents did not drink daily; of those who did, more men than women exceeded guidelines for long-term risk.

Friends also had a strong influence. Almost 40% of those who had at least one friend who drank alcohol had tried alcohol themselves, compared to only 5% of those who had no friends who drank.

Teens were also more likely to have tried alcohol if they were the only child, in the later stages of puberty, or in a single-parent household. But even after accounting for all these factors, there was still a significant association between parents’ drinking habits and adolescents’ alcohol use. Those whose parents drank at a risky level were most likely to have tried alcohol.

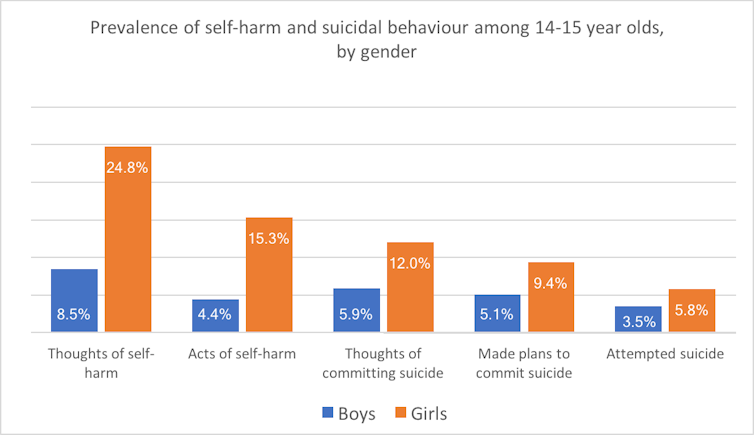

Rates of self-harm and suicidal behaviour are high

One in ten 14-to–15-year-olds had self-harmed in the previous 12 months, and 5% had attempted suicide.

Girls appeared to be at greater risk than boys of both self-harm and suicidal behaviour. However, boys were much more likely to act impulsively and make an unplanned suicide attempt.

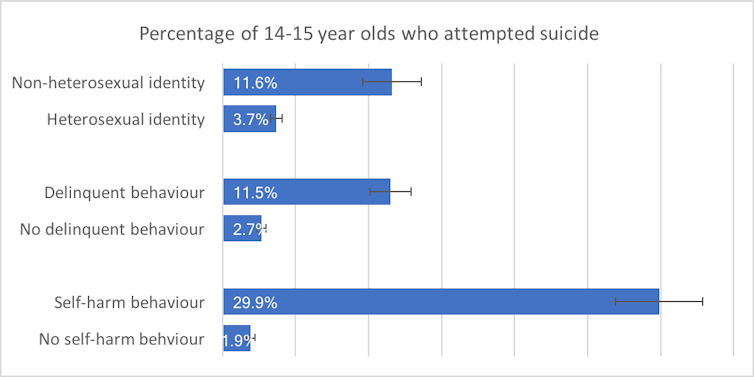

Some teens are more at risk of self-harm than others. Those who were same-sex attracted, bisexual or unsure of their sexuality were at greater risk of self-harm than heterosexual teens.

The risk of self-harm was also higher among teens with more reactive temperaments, depression, anxiety or general feelings of unhappiness and those who reported being threatened or feeling victimised by their peers because of their health, skin colour, sexual orientation, language, culture or religion.

Self-harm can often act as a “gateway” to suicide. Of those who had attempted suicide, two-thirds had previously self-harmed.

Teens were at higher risk of suicide if they were same-sex attracted, bisexual, or unsure of their sexuality; or if they had been involved in so-called “delinquent behaviour” such as crime or property offences. Of those who attempted suicide, 22% had done so more than once and 14% of boys and 18% of girls had required medical treatment after a suicide attempt.

Teens employed in part-time jobs

At 15, almost 40% of young people had worked in a part-time job. Of those working, around one-third worked informally in a family business or for themselves. Most worked during the school term, with 18% of boys and 25% of girls working on weekdays.

Compared with teens living in the city, those in regional areas were more likely to be employed.

And while girls were more likely to be employed than boys, in regional areas a higher percentage of boys were working. This might reflect the types of informal work available regionally, such as farming and labouring work.

Young carers falling behind at school

At least one in ten 14–to-15-year-olds were providing informal care for a household member, with around two-thirds of this group helping with core activities including personal care, mobility and communication.

On average, young carers have lower performance levels in NAPLAN reading and numeracy than their non-caring peers. Young carers who provided daily care were more than a year behind their classmates.

Teens at risk need extra help

While most teens are doing well, some teens would benefit from extra help. Parents, teachers and friends of young people need support and advice to know how to help those at risk.

Programs to assist young carers to participate fully in school would be of considerable long-term benefit. Increasing awareness of risk factors for self-destructive behaviour in young people could potentially reduce this disability burden.