Australians are used to the vulgar antics and empty point-scoring that pass for debate in federal parliament. But little could have prepared them for the current descent into pure farce.

Politics divorced from political reality

The US has been engulfed by a political tsunami few predicted and many are struggling to comprehend. Much of Europe is still weathering the storm of an unprecedented influx of refugees at a time of high unemployment and little prospect of economic growth.

Financial markets, climate change negotiations and great power relations are precariously poised.

Amid this turbulence, federal parliament’s last sitting week for 2016 was devoted to the backpacker tax, legislation to bring back the Australian Building and Construction Commission, and the political future of Attorney-General George Brandis.

There has never been a time when the disconnect between political elites and the public interest was greater than it is today.

The major parties seem uninterested or unable to respond to a drastically transformed political agenda. And so the disconnect grows wider by the day – and the contradictions ever sharper.

Shirking economic realities

On returning from the APEC meeting in Lima in November, Malcolm Turnbull reiterated his support for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). This came just as US President-elect Donald Trump announced that US withdrawal from the TPP would be one of his first acts on assuming office.

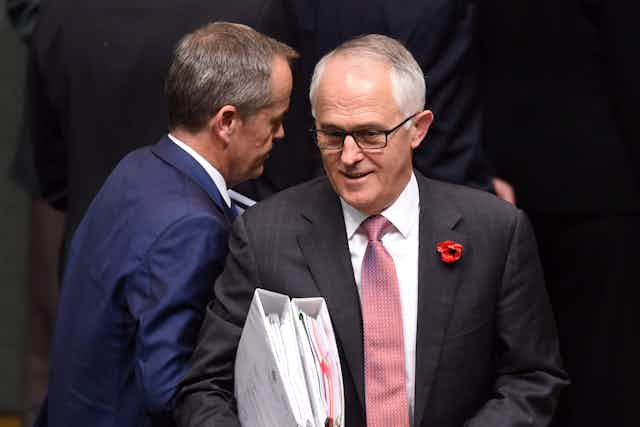

Turnbull has repeated the mantra of free trade, growth in trade, and the benefits of an integrated world economy. This is despite large segments of Western electorates that have suffered the ravages of globalisation turning in anger and frustration to populist slogans and movements that seek to fill the political vacuum by crude appeals to nationalism, prejudice and xenophobia.

Both of Australia’s major parties remain ardent advocates of free trade, yet seem oblivious to growing economic inequality. They remain preoccupied with reducing budget deficits and averse to imposing higher taxes on rich people and corporations. This means they have effectively deprived themselves of the levers they need to remedy the glaring gap in wealth and income.

Glib references to the benefits of innovation are no substitute for thoughtful planning and targeted support for new environmentally and socially sustainable industries.

Strangely, the argument implied – though never explicitly stated – is that the benefits arising from the free movement of goods and services somehow do not apply when it comes to the free movement of people.

In recent months, Labor leader Bill Shorten has struck a shrill populist tone, calling for restrictions on the issuing of 457 visas to skilled foreign workers.

The ties that bind

The case for Australia to review the US alliance is gaining currency. The reasons go well beyond the Trump victory, deeply disturbing as it is. They include:

the dismal state of American political life;

the continuing obsession with “American greatness” – whether to restore it (à la Trump) or to preserve it (à la Hillary Clinton), when all indicators point to steady decline;

the souring of relations with Russia;

hopelessly ill-conceived adventures in Afghanistan and the Middle East; and

importantly for Australia, a troubled relationship with China.

Yet Turnbull has found comfort since the US election in repeating old mantras. He has argued for a continuing strong US presence in the region as the key to peace, stability and prosperity, and assured Australians the alliance will remain strong for years to come.

Recently, Turnbull directed his venom at the shadow foreign minister, Penny Wong, for daring to propose a slight shift in emphasis toward greater engagement with Asia.

As it happens, Wong’s comments were rather timid. They did not question Australia’s expanding military and intelligence connections with the US, its continuing involvement in US foreign military deployments, support for US nuclear strategies and capabilities, or the wisdom of hosting the highly secretive Pine Gap facility.

Apart from its potential involvement in nuclear war fighting, Pine Gap is widely thought to contribute targeting data to US drone operations. These include assassinations that may be in breach of international law. There is no suggestion Labor is about to press the reset button on any of this.

Policies adrift

At a time when the number of people displaced by persecution and violent conflicts reached a post-war record of 65 million, Immigration Minister Peter Dutton inexplicably set out recently to question the value and wisdom of Malcolm Fraser’s generous refugee legacy.

Neither major party is yet ready to tackle the problem of boat arrivals through a regionally negotiated solution consistent with international obligations – as opposed to secretive, costly and ill-fated bilateral deals.

The same storyline emerges when it comes to environmental regulation, fostering a new discourse on Islam based on respect and understanding, or the protection of human rights.

In recent years, draconian legislation has severely restricted civil liberties – whether in the name of national security, countering violent extremism, maintaining commercial confidentiality, or thwarting whistleblowing.

These laws remain largely intact. But the government has now reopened parliamentary debate on the Racial Discrimination Act – in particular Section 18C – ostensibly in defence of free speech, when the sole intent and effect of the legislation is to discourage racial vilification.

Green aspirations

The Greens often present alternative, generally well-intentioned proposals.

However, neither singly nor collectively have they been able to stimulate the national conversation Australia so desperately needs to have. Many factors are at play here.

The Greens are not, at least not now, able to command the attention of a wide public. Their forays into political discourse are seen by some as little more than expressions of wishful thinking, and by others of more cynical disposition as clever ploys to appeal to disaffected Labor voters.

For others still, the Greens’ approach is far too electoralist to offer a genuine alternative to politics as usual.

In search of a new narrative

The problem, however, goes much deeper.

What the Greens have not managed to do, and the major parties have not even attempted, is to forge a new, coherent, sustainable and compelling narrative of Australia’s past and future.

What’s needed is a narrative that tackles the profound transformation of Australia’s economy, society, culture and environment over the last 20 or more years. It must respond to the seismic global shifts in geopolitical, civilisational and economic relationships, as well as in the planet’s fragile ecology.

Such a narrative needs to give due weight to promising new directions, but also to costly wrong turns and more often than not to a state of virtual political paralysis – in Australia’s parliament as in the UN.

It follows that such a narrative cannot be constructed overnight or from the top down. It has to emerge organically from the diverse efforts of civil society, as it seeks to take stock of unprecedented risks and exciting new opportunities, not alone but in tandem with similar efforts in other parts of the world.