China’s biggest search engine has a constitutional right to filter its search results, a US court found last month. But that’s just the start of the story.

Eight New York-based pro-democracy activists sued Baidu Inc in 2011, seeking damages because Baidu prevents their work from showing up in search results. Baidu follows Chinese law that requires it to censor politically sensitive results.

But in what the plaintiffs’ lawyer has dubbed a “perfect paradox”, US District Judge Jesse Furman has dismissed the challenge, explaining that to hold Baidu liable for its decisions to censor pro-democracy content would itself infringe the right to free speech.

Search engines = newspapers?

Judge Furman said Baidu’s censorship was just like the editorial judgements made by other kinds of publishers, including newspapers.

It’s no secret that search engines make decisions about the information they present, and this is often a good thing. One of the reasons for Google’s massive popularity is that it is much better at returning relevant results than any other search engine.

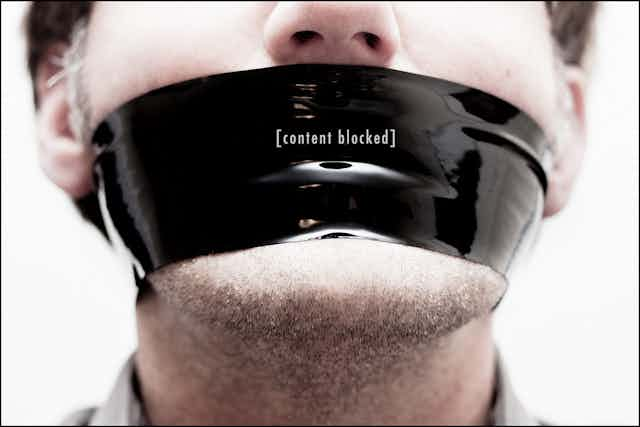

But search engines are not exactly like newspapers. While we expect and learn to accept the editorial bias of our newspapers, the bias of search engines can be much harder to detect. It can be hard to know what information is being left out when you don’t know what you’re missing.

We also have laws that limit the ownership of media companies to ensure that the views of any one organisation don’t dominate the market.

We expect a level of objectivity from search engines that we might not demand of media companies. Rightly or wrongly, we expect our search engine results to be accurate.

For the most part, our search engines return unbiased results and try to be transparent when they are required to block content. Because most of the services we rely on are based in the US, the US First Amendment protects the practical right of Australians to access information. But it also means that private organisations, including search engines, have no obligation to return uncensored results, and no need to be transparent about what they decide to block.

In the online environment, private companies play a vital role in how we access and share information. From search engines to social media sites, we rely on these organisations to make decisions about what content we are able to see and what we are able to say.

These decisions are not made in the same democratic way that our conventional censorship laws are; they are made by tech executives who we cannot vote out and whose decisions we cannot appeal.

As the debates about what material should be accessible online continue, it will become more and more important for the policies and procedures of these organisations to reflect community values.

For the moment, this has generally been in the financial interests of these companies, because citizens have a choice about the services they use. Judge Furman explained that if a user is dissatisfied with Baidu’s search results, he or she

has access, with just a click of the mouse, to Google, Microsoft’s Bing, Yahoo! Search, and other general-purpose search engines, as well as to almost limitless other means of finding content on the internet.

Search engines should not have to be “neutral”, because it would limit their ability to provide useful results. But their power in helping us communicate and the secret nature of their algorithms means that they should at least be clear about the types of decisions they do make.

The biggest implication of the US Court’s decision is to highlight how important transparency and competition is in the online environment. Without the ability to know what is being censored, or effective competition between providers, private decisions can pose a real threat to free speech.

The reality in China

China’s comprehensive censorship scheme provides an extreme example of how important transparency and competition is to free speech.

This year China was rated 175th out of 180 countries in Reporters Without Borders’ annual World Press Freedom Index (the Chinese Community Party promptly banned the publication of the Index).

All search engines with servers in China, including Baidu, conform to Chinese law by sanitising their results. For other search engines, including Google, users who search for banned words will find themselves temporarily cut off from the search engine.

The key to the effectiveness of China’s great firewall is that it is difficult for Chinese citizens to know what, exactly, is being blocked.

Anybody in China trying to learn about the case might search for “网络封锁” (“internet blocked”), or browse China’s two biggest news services, Xinhua and China Daily, and find … nothing.