In the English-speaking world, the hashtag #MeToo is used to condemn sexual harassment and assault. In France, the equivalent is much more pointed: #BalanceTonPorc, or “denounce your pig”.

The meaning is instantly clear, but you might ask yourself, why the pig reference and what does it actually stand for? And what does it tell us about the hashtag itself? Is it just an insult, or a negative reference to animals? The hashtag was first used by Sandra Muller on October 13, 2017, two days before #MeToo went viral. In an article in the major French daily Le Parisien, she explained the reason for her choice:

“It is really strong as an image and it helps to create distance from the perpetrator. It also has a vulgar and working-class connotation.”

The hashtag was also a direct reference to the unflattering nickname of American film producer Harvey Weinstein, privately referred to as “The Pig” at the Cannes Film Festival, at the centre of a still-widening sexual harassment scandal.

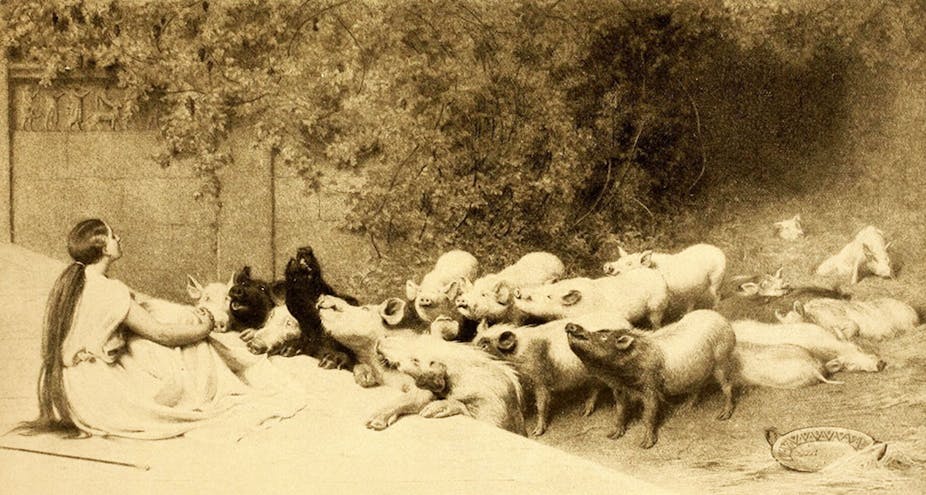

Vulgar indeed. But the use of #BalanceTonPorc was perceived as a welcome inversion of situations – especially sexual – where women have often been portrayed or referred to as pigs. A simple search on Pornhub reveals an endless range of porcine expressions or images that are used to animalise women. But long before the world of Internet pornography, pigs have been widely used as a metaphor for sex or lust, both in France and around the world.

So let’s take a look at the how the images surrounding our porcine cousin have evolved and been used, both by feminists and antifeminists.

‘Hoggish discourse’

In France, #BalanceTonPorc is situated within the long tradition of hedonist grivoiserie, a hoggish discourse that goes back to the celebrated and licentious Marquis de Sade. It is perfectly expressed in the moral of the ribald song “La Rirette”, from the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It describes a rape and reminds women not only that “men are pigs” but also that “women like” such “pigs”.

Now let’s jump to the 20th century. The association between pigs, men and lust has by now become universal, as expressed in the classic French movie La traversée de Paris (“The Crossing of Paris”), directed by Claude Autant-Lara and released in 1956. In the film, actor Jean Gabin says: “There is a pig asleep in every man’s heart”.

Throughout the 20th century, pig and porcine references remained linked to sexual desire and of men lusting after women. But it gradually grew into a stronger symbol, one that rose in the late '60s and inscribed itself into the feminist discourse while, at the same time, echoing sexual liberation.

Post-‘68 radical feminism wave

In late 1960s the word pig was added to the term “male chauvinist”, which was used in the 1930s to denounce a man for his exaggerated patriotism. A newly forged expression, “male chauvinist pig” (MCP), was born in the context of major feminist protests in the United States against the Miss America pageant (1968), the sit-in at the Ladies’ Homes Journal or the Women’s Strike for Equality (1970) in New York City.

For the generation that grew up with George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945), the use of the pig metaphor to denounce political oppression and inequality was almost inevitable.

In the 1960s, pig was also a common slang term for policeman, and was given a particularly dark twist in the “Black Panther Coloring Book”, “Off the pig!”. We were also are in the time period between the Beatles song “Piggies” (1968) and Pink Floyd’s “Pigs (Three Different Ones)” (1977).

In a 1970 column in the New York Times, humourist Russell Baker notes that to insult a policeman as a “fascist, racist, sexist, chauvinist, swine pig!” would sound “very up to date.” Hence, by using the term pig, “feminists tried to show their fellow male protestors that oppression of women was a fact of life in everyday radical politics”, as Gloria Kaufman wrote in 1980.

The addition of “pig” to “male chauvinist” gave the phrase greater appeal, first by helping someone understand what chauvinist meant, and second by allowing it to pass as a joke. The word pig turned the assumption of the male chauvinist’s own superiority on its head. As American feminist leader and journalist Gloria Steinem explained in 1979, “years of being 'chicks’, ‘dogs’, and ‘cows’ may have led to some understandable desire to turn the tables.” Indeed, in some ways the figure of the “male chauvinist pig” is a response to the Playboy bunny.

Antifeminist reactions

The term gained so much attention that antifeminists could not stay silent. They reacted through derision, positive identification – proclaiming themselves to be MCP – and sexually twisting the whole expression.

For example, the comic Avengers (1970) presented a caricature of the feminist movement. A new feminist warrior called Valkyrie was introduced; she was a villain who manipulated the female heroes (Lady Liberators) by pretending to free them from male domination. On the cover of the comic, Valkyrie is represented putting her foot on the head of Superman while saying, “All right girls – that finishes off these male chauvinist pigs!” In another scene she says, “Up against the wall, male chauvinist pig!”

In fact, this was the title of the first major article that Playboy dedicated to the Women’s Liberation Movement in May 1970. The same year, while Hugh Hefner was debating two feminists on The Dick Cavett Show, female activists stormed the stage shouting at Hefner, “Off the pig!”. Hefner felt that Women’s Liberation threatened what he saw as manhood and sexual liberation.

In 1973, retired tennis champion Bobby Riggs even bragged that the women’s game was so inferior to the men’s that he could, at age 55, beat the top female player, Billie Jean King, just 25 at the time.

In practice sessions Riggs sported a “chauvinist pig” T-shirt – a token like many other self-declared antifeminist partisans then – and even announced, “If I am to be a chauvinist pig, I want to be the number-one pig.” Before the start of the match, he presented King with an extra-large Sugar Daddy lollipop, while she presented him with a piglet.

The end result? Riggs lost. Still, the match got a big-screen remake more than 40 years later, The Battle of the Sexes, directed by Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris and starring Emma Stone and Steve Carell.

Porn’s reappropriation

The most radical way of subverting the feminist “pig” message was found in pornography, which in the United States boomed under its “porno chic” period between 1969 and 1984. Some of those movies were openly antifeminist, such as Women in Revolt (1971), produced by Andy Warhol. In the film, the radical women’s liberation group is named Politically Involved Girls – PIG.

The 1972 pornographic movie The Pigkeeper’s Daughter multiplied the associations between women, pigs and sex. A year later, the movie The Erotic Memoirs of a Male Chauvinist Pig continued this attack on feminism in a more hard-core form.

The creation of Miss Piggy

Such a context was propitious for Jim Henson, the creator of the puppet character Miss Piggy. She was born out of Hensen’s imagination and joined The Muppet Show in 1976. The blond pink sow is the opposite of her love interest, Kermit the Frog: she is egocentric, feminine and quite promiscuous.

While she was a powerful female character with karate skills – it’s impossible to forget her shouts of “hi-yah!” – she also embodied the cliché of modern liberated women, a carnavalistic figure of the “woman on top”.

Yet over time, the evolution of her character – excessive, eccentric and transgressive – transformed her into a figure of change. So much so that 40 years after she was created, Miss Piggy received the Gloria Steinem First Award from the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum.

From 1968 to 1972, the use of the porcine metaphor in the cultural battle between feminists and antifeminists pushed the limits of the associations between pigs and sex. American slang was filled with terms like “hog” (penis), “to make piggies” (have sex), “beat the hog” (masturbate), “to hog” (to rape) and “pig pile” (a homosexual orgy).

The continuous references to violent sexual behaviours and pigs gradually made the use of such terms more and more frowned upon, especially in popular culture in the United States.

The twist: Lady Gaga, DSK

In 2011, the head of the International Monetary Fund, French politician Dominique Strauss-Kahn, was accused of sexual assault by an employee of a New York hotel. The cover of Time magazine featured a pink pig with the headline: “Sex. Lies. Arrogance. What Makes Powerful Men Act Like Pigs?”

The cover echoed earlier ones by Time, including a 1994 issue showing a pig in a suit asking, “Are men really that bad?”, and a 1973 one featuring a man with a pin that reads – yet again – “male chauvinist pig.”

In fact, the porcine metaphor was used by the media from the beginning of the Dominique Strauss-Kahn scandal, in a continuation of a common way of denouncing sexual harassment and violence. The events themselves formed the basis for Abel Ferrara’s 2014 fiction film, Welcome to New York, starring Gérard Depardieu.

In pop culture, Lady Gaga deals with the subject of rape in a 2013 song, “Swine”:

Do ya I know I know I know I know you want me

You’re just a pig inside a human body

Squealer squealer squeal out you’re so disgusting

You’re just a pig inside

Swine x 4.

The US presidential elections in 2016 gave another twist to the “pig” expressions: sexism in politics was real, loud and provocative, and women had enough.

Alicia Machado, winner of the 1996 Miss Universe pageant, stated that Donald Trump called her “Miss Piggy” and also “Miss Housekeeping” because of her Hispanic background. During the first presidential debate on September 23, 2016, Hillary Clinton brought up Machado’s statements about Trump.

It was in this context that the Harvey Weinstein case erupted, and with it, #BalanceTonPorc.

In a way, the paradigmatic changes during the period of sexual liberation forced us to accept our porcine nature. But they also obliged us to negotiate, at least symbolically, the limits of our porcinity and humanity. The hashtag #BalanceTonPorc is inscribed in the continuity of this process.

Forthcoming with David Nadjari: “Le complexe du cochon ou la fin du modèle français d’intégration”, Paris, Arkhê, 2018.