The redevelopment of Sydney’s Barangaroo into a $6 billion waterfront precinct has involved some of Australia’s most influential people - including former Prime Minister Paul Keating and businessman James Packer.

But just how tight is this circle of political and business influence figuring prominently in decisions around some of our most treasured public land?

In our second piece in our series on Barangaroo, lecturer Mark Rolfe from the University of News South Wales writes of the connections between our politicians, players and our favourite pastime, property.

No doubt there is now around Australia a certain smugness about yet another tale of “Sin City” Sydney and its sleazy trades. After all, the counsel assisting the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) has compared the infamous Rum Corps to the deals in coal exploration licences by Eddie Obeid, a dominant factional leader of the NSW ALP.

This comes on top of allegations about the acquisition through his front companies of three leases of government property in Circular Quay from a Labor Party donor.

Yet such excitement obscures a more routine, legal but no less important point about the networks connecting business and political parties that have often pushed the public aside, even when public land has been involved. We are often treated as irritants and voyeurs to political processes, watching from the bleachers as Americans would say.

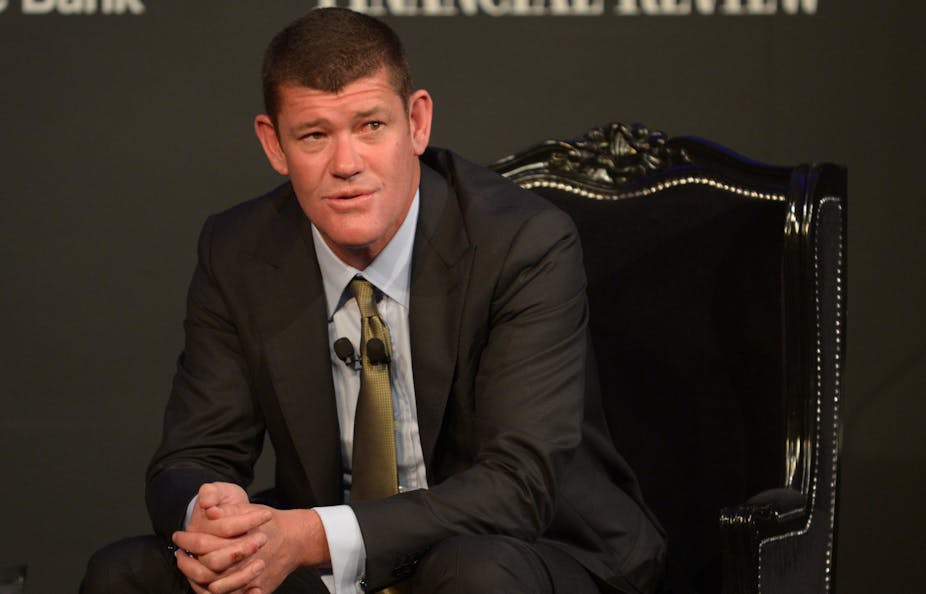

I give you three words that say it all but which typify much Australian history – Packer, gambling and Barangaroo. And I give you one more word – “pissants” – which is Packer’s view of the journalists at the Sydney Morning Herald for calling him to account. But it also typifies more generally the disdain which some elites hold for the public, even when they are pursuing public land.

The biggest laugh I got out of the Barangaroo deal was after Packer claimed that lobbying played no part in the approval of a second casino licence for Sydney, to be housed in a $1 billion hotel complex at Barangaroo; it was due purely to being a good idea.

I admire his capacity to keep a straight face since he discussed his plans with Premier Barry O’Farrell in August and one week later the government changed the guidelines for unsolicited proposals for projects by the private sector. The rules had only arrived in July.

Packer also employed Mark Arbib and Karl Bitar, both of them former secretaries of the NSW branch of the ALP, who lobbied the leader of the tragic rump of that party in the state parliament, John Robertson.

As a sociable sort of fellow, Arbib also took the secretary of the hospitality workers union to a match between the Sydney Swans and Hawthorn after a memorandum of understanding was signed between the union and the Packer company Crown Ltd. This was a stunning reversal of union opposition in June.

I was still laughing heartily when I remembered an article by Stephen Loosley. Arbib had followed this man, who had himself followed the career path blazed by Graham Richardson with ascension from secretary of the branch to senator and then resignation to become a lobbyist. Richardson was a senior minister and factional operator in the Hawke government. Loosley is now with Minter Ellison as a strategic counsel with “specialist experience in international affairs, public policy, legislative process and major infrastructure projects”.

Loosley wrote of a private dinner in 2006 between James Packer and Morris Iemma, Labor premier of the time, which led the government to grant a gambling licence to Betfair in NSW. Iemma’s mentor was Richardson who, along with another Labor stalwart Peter Barron, had associations with Packer’s company PBL which had an interest in Betfair.

With Iemma we come full circle back to Obeid who, with Joe Tripodi as another factional leader, deposed first Iemma and then Nathan Rees before installing Kristina Keneally. Her term as Premier was immediately crippled when Rees denounced her as the puppet of Obeid and Tripodi. I haven’t even mentioned the problems that were happening down in Wollongong.

One of the few things Rees achieved during his short term was a ban on political donations from developers. This was the action of a desperate man who realised the tides of political manure were lapping the nostrils of the ALP.

Voters thought Labor was rolling in sacks of developer money, over $10.4 million between 1998 and 2007. Few noticed that NSW Liberals received $7.9 million during that same time. Paul Keating rightly called for a ban on this “wall of money”, as did the Urban Taskforce. But that has still left Keating to wield his political influence with Packer in settling the arrangements for Barangaroo.

We have seen it all before. We can see the connections between our politicians, our national hobby of property dealing and overseas sources of finance.

During the 1860s-90s all the colonial governments borrowed heavily from London to develop, but Melbourne gushed even more with English pounds. Many politicians – premiers, ministers and backbenchers – enriched themselves by voting for spending on infrastructure, particularly for railway lines that, coincidentally, just happened to pass through the suburbs that they developed as directors of companies. Then they sold the blocks at increased prices. This nice little earner collapsed in the depression of early 1890s.

Alfred Deakin achieved justifiable fame as our second prime minister but at this stage he achieved justifiable shame as one of these scoundrels.

Another politician was William Lawrence Baillieu (ancestor to the current Victorian Premier Ted Baillieu?). A friend described him as “one of the wicked bears who are always ranging around the world with a view of getting as much out of it as possible”.

Let us jump a few decades.

In the 1980s Sydney overcame Melbourne to become the financial and corporate headquarters of Australia and a global city, thanks to the policies of the Hawke government and to globalisation. It was important not only for NSW but also for the Australian economy. Hence, state and federal policies pushed Sydney on the global stage to create economic growth and jobs. That’s why we had the Olympics - following in Melbourne’s 1956 footsteps - and that’s why the city had a building boom in the nineties.

As a consequence, real estate companies and associated producer service businesses jostle with each other and with other sections of capitalism to lobby for influence on the NSW government.

This is why the NSW ALP was so enmeshed in the politics and donations of property development and that is also why we have had powerful groups such as the Urban Taskforce, the Property Council of Australia (which advertised recently for a lobbyist to replace the ex-speech writer for Kevin Rudd) and the Committee for Sydney, of which Loosley is a former chairman. As Pauline McGuirk found in 2003:

…there is a group of private sector and non-government organisations with a permanent presence in Sydney’s governance landscape. In the private sector, a series of general business associations and specific business practice groups represent the major fractions of capital that dominate global Sydney: financial and business services corporations, property development and investment interests, major manufacturing corporations, retail, and tourism interests.

Not much has changed under Barry O’Farrell. The Mars Group is an apartment developer mentioned in this report in 2006 on developer donations. Now it is a client of 1st State, a government and public relations firm with former Howard minister Peter Reith amongst its number.

So what happened when political donations from developers were banned in NSW? They fled to other states of course!

There’s nothing like the old Australian tradition of property development.

Read part one of our series: Barangaroo: the loss of trust?