During a 1988 excavation on London Wall 39 human skulls were discovered. But they remained shrouded in mystery. Now though, forensic analysis of the skulls by bio-archaeoloist Rebecca Redfern, shows that their owners, most of them adult males, were the victims of a remarkable level of violence, not just because of the way they died, but the manner in which they lived. The exact source of this violence, however, remains uncertain.

Many of the individuals represented in the London Wall excavation had clearly suffered an attack with weapons and had been decapitated. We know the skulls were deposited into a series of waterlogged pits and ditches in what was then an industrial area by the edge of the Roman city around 120–160AD.

According to newspaper reports they might have been barbarians from what is now Scotland, captured during Roman campaigns on the northern borders of their British province and brought back to London to be ritually slaughtered. Conflicts on the margins of Britannia could certainly form a context for the execution of captured fighters and the display of their remains.

Hadrian’s Wall was built around 120AD, following conflicts with the northern Britons. The Antonine Wall was then constructed further north during the 140s. The brutal control tactics of the Roman army included putting on display the dismembered bodies of those that resisted them. Excavations of the fortress ditch in Colchester by archaeologists in the 1980s found remains, which were probably displayed around the gateway to this Roman city around 50AD. The London Wall skulls may represent the display of human remains at the city boundary, commemorating the Roman military victories in the North.

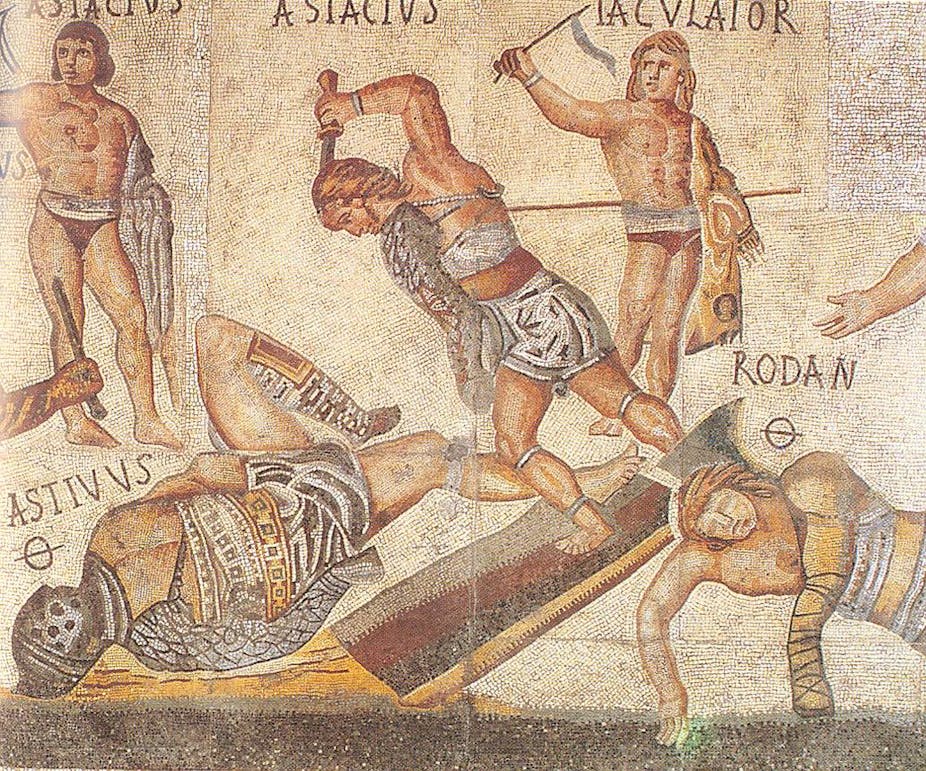

The skulls could also belong to gladiators or to the victims of gladiatorial combat. A Roman amphitheatre was discovered on the site of the London Guildhall in 1988. This substantial building, perhaps seating an audience of 10,000 people, shows the great popularity of gladiatorial spectacles in Londinium.

Nick Bateman of Museum of London Archaeology, who has examined the finds from the city, shows it is apparent that by the mid-second century, Londinium was probably the capital of the province of Britannia. A cosmopolitan place, its inhabitants had arrived from across the Roman world and many probably attended the imported Roman practice of the gladiatorial games.

If the skulls from London Wall can be linked to such combat, that still doesn’t explain why they were transported 300 or 400 metres from the amphitheatre to be deposited in an industrial area at the boundary of the city. And why only bury the skulls (only a scattering of other human bones were present).

These skulls may represent part of a very long-lived tradition of depositing human heads in watery locations in Londinium; rivers, streams, ditches and pits. The great number of skulls found in the Thames and the subterranean Walbrook stream suggest that a head cult was practised in Roman London. In 1998 a remarkable find was made in the Roman settlement of Southwark, to the south of the Thames which may shed light on these London Wall skulls.

At the Old Sorting Office site in Swan Street, the remains of a man’s body were found in an interesting position. They were deposited upside-down in a pit close to the margins of the urban area. Research shows that the body may have been through excarnation – the burial practice of removing the flesh and organs of the dead, leaving only the bones. This suggests that human bodies were exposed on the margins of the Roman city and then used in cult practices related to ancestors, perhaps continuing prehistoric traditions on the margins of the Roman city.

Whatever the reason for these skulls being deposited at London Wall, this groundbreaking research adds to our knowledge of the violent times in which their owners lived – and makes it clear they came to a bloody end.