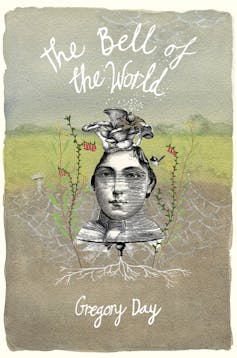

Gregory Day’s The Bell of the World is an ambitious, strange and marvellous novel.

Day has long carried out a determined and idiosyncratic writing practice of paying attention, in writing, to where he lives on Wadawurrung and Gadubanud Country. In the introduction to his excellent collection of nature writing, Words are Eagles, he considers the complexity of

writing in this polyphonous country that is now Australia […] How to describe it without betraying it. How to love it without destroying it. How to learn from it and listen to the lessons it has to impart.

In The Bell of the World, he gives this project full flight.

Review: The Bell of the World – Gregory Day (Transit Lounge)

The vehicle for the novel’s exploration of the loving and fraught entanglements of art and nature, human and non-human, in settler-colonial Australia is Sarah Hutchinson, a very odd girl living some time in the early 20th century.

As readers, we are used to developing a sense of character with reference to how someone interacts with the social world. With Sarah Hutchinson, Day attempts something quite different. Sarah is unmoored from her social context or situation for much of the first part of the novel.

To apprehend a character whose main points of reference are in the natural rather than the social world is a difficult task for novelist and reader alike, and I struggled with Sarah for much of this section. She is first flung out of an unloving family into a miserable British boarding school, then into the milieu of her loving uncle Ferny – a cosmopolitan, queer farmer and naturalist, who is residing in Rome with his battered copy of Joseph Furphy’s Such is Life.

Ferny’s posse of artist friends provide Sarah with a thrilling but destabilising education. This rackety way of learning about how to be with others leaves Sarah in a state of deep distress akin to trauma, as she is deposited in a house in the bush with a woman who has much deeper roots in that place than Sarah and her family. She emerges from this trauma by means of being outside and seeing what is there.

The novel proceeds to set out a philosophy for a way of living and writing that Day has practised throughout his career to date. It stresses the importance of attending to a particular place and its ecology with detail, care, respect and humour. Sarah learns to do this on the Ngangahook Run: land farmed by her family for generations, which seems, at first, to promise an arcadia where art, nature and love can coexist.

A unique perspective

The Bell of the World forces the reader to slow down and attend. Sarah’s is a unique perspective. Everyday activities become odd and multifaceted when seen through her eyes. Adjectives abound: a journey in a gig becomes “a shawled and shuddery survey of the nearby but seldom-seen ground”. The effect is a little like reading Patrick White: there is so much – sometimes too much – inner consciousness sparking off and interpreting the world in novel ways that the larger sense of what is happening and who is apprehending it recedes.

Day is at his best when he grounds his runaway multidirectional novel. Concrete but resounding moments of social interaction reveal multitudes about the world in which Sarah is jangling around, and about why the novel’s philosophical argument about nature is so important.

One such moment is a conversation about the bell that some locals want to build in the church. Sarah’s uncle Ferny tells them straight: for the Aboriginal people of the region, the bell would sound not of progress but brutality. The bell is an imposition of settler-invader voice across the ecology of the place, and one that resounds with memories of colonial violence for the local First Nations people.

The bell proponent proceeds with an expectation that he will not be brooked; Ferny, with a sentence, brooks him. This sets off a cascade of events that upends Sarah’s sense of her relation to the world.

The novel expresses a profound optimism about the prospect of a settler-invader way of being with nature in Australia that does not seek to dominate but to know and care for it. This optimism is tempered by reminders of how alien this way of being seems to a culture grounded in the domination of others. The reader is immersed in Sarah’s first-person perspective for such a long stretch that we could forget that she doesn’t know a lot about the community of people in the town. Her shock, when their distrust of difference explodes into violence, is ours too.

Read more: Kim Mahood's Wandering with Intent redefines the Australian frontier

Infra-ordinary

At one point, Sarah’s meandering internal monologue settles on the term “endotic”, which she says is “the opposite of exotic”. The word just sits there, confusing. It is not listed in the OED. It sent me down a rabbit hole that led to the musings of the French experimental writer Georges Perec about an anthropology of the “infra-ordinary”. In 1973, Perec asked:

How are we to speak of these “common things”, how to track them down rather, flush them out, wrest them out from the dross in which they remain mired, how to give them a meaning, a tongue, to let them, finally, speak of what is, of what we are. What’s needed, perhaps is finally to found our own anthropology, one that will speak about us, will look in ourselves for what for so long we’ve been pillaging from others. Not the exotic any more, but the endotic.

Gregory Day’s writing has long been interested in the “infra-ordinary”. It draws together the everyday detail of both human and non-human lives. Day’s curiosity about language is annoyingly infectious, and has me thinking about the complexity of the idea of the “endotic” in a settler-colonial context, entangled in the fraught nature of terms like invasive, introduced, native species. What he is trying to do here is imagine what the endotic might mean in this place. It is big-picture thinking.

The means by which Day carries out this experiment is primarily aural: moments of numinous experience for Sarah are tethered to “sound-made matter”. This is absolutely quotidian: creaking harnesses, swearing men, rustling grass. Sarah is trying to find a way to allow the sounds of the natural world, “the wild and ferny worlds upstream, to intervene”.

The Bell of the World is also full of tender, understated interpersonal relationships, which take place against the backdrop of receptive natural worlds and dysfunctional social ones. These relationships are observed in their dailiness, placed on an equal footing with observations of the non-human life on the Ngangahook Run.

The music of place

The closing chapters of The Bell of the World are breathtaking. They involve two contrasted set-pieces of communal listening: one in a city concert-hall (a collision of real and fictive worlds), the other as dusk falls on the Ngangahook Run. Literature points us to music as an art that enables its audiences to listen to the world around them. It encourages them to hear the oldest stories of this place, and new ones too.

In this sense, Day is echoing what First Nations writers in Australia have been saying with their work for decades now: listen to this place and the people who belong here. Pay attention! The Bell of the World models a ceding of authority that is grounded in the belief that forms of connection – underground, across air and ocean – are possible.

The notion of artistic production that emerges from the pages of The Bell of the World is not one of solitary genius, but rather of an artist in deep conversation with the plants, animals and soil around him, as well as with the works of other artists near and far. Day’s novel is clearly in conversation with Joseph Furphy, Herman Melville and Patrick White, but it also seems to me to be carrying on a more profound conversation with other big (in all senses of the term) novels of recent decades: those of Alexis Wright and Kim Scott.

The tragic-comic presentation of parochial yet homicidal townsfolk, the attempts to centre attachment to place and have the living ecology of that place fill the page, the use of disorienting narrative modes, the scenes of failed and hopeful listening – all of these things suggest to me that Day is a novelist who has been doing some good listening of his own.

There is a joyful and laudable ambition to this novel, which seeks to tell a big and true story about being in this place, while pointing to how it might be possible to make and attend to art in it. In the course of one of its many reported conversations about fiction itself, its characters speak about writing which might at once hold “much humorous companionship” and be “a lively and enigmatic seedbank” for ideas and ways of seeing. The Bell of the World finds an unruly way of being both.