I found myself in wholehearted agreement with Boris Johnson, as he took the opportunity of his trip to China to express his opinion that British children should learn Mandarin.

China has come a long way in a very short time. A century or so ago, Britain considered China so backward that it had few qualms about invading the country several times in order to impose its own way of doing business. Half a century ago, China had become the Communist enemy and converting it to “our way” of life seemed of crucial importance.

Now the tables have turned. China has had an economic miracle and its growth figures represent a beacon of hope amidst global financial misery. Many Chinese people are rightly proud of the fact that, this time around, the British are politely asking for business rather than enforcing it with gunboats. But will China achieve what no other nation has accomplished in recent history? Will it make Brits bilingual?

The signs are certainly encouraging. More than three quarters of UK universities now offer elective courses in Chinese. Primary and secondary schools around the country have started to include Chinese into their curricula in the same way that they have traditionally included French. At least one school in Hampshire has started to offer Mandarin as a total immersion subject, meaning that pupils are taught all lessons in that language. Chinese Sunday schools traditionally aimed at educating pupils of Chinese descent now increasingly receive applications from non-Chinese parents.

This all relates to the growth of UK businesses operating in China. These companies are increasingly interested in attracting British speakers of Chinese to complement the skills of their English-speaking Chinese staff. Meanwhile, the Chinese government is doing its bit by setting up Confucius Institutes and supporting Confucius Classrooms all over the country.

This is often perceived as a bid for soft power. The Chinese government wants to promote understanding of its culture as it sees it, rather than how it is seen by western “China watchers”. Language pays a key role in this inherently ideological process.

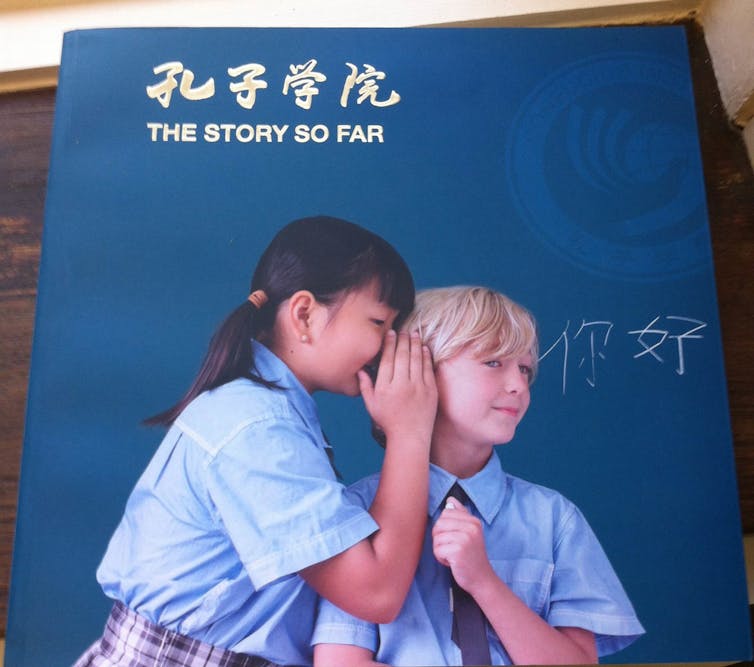

On the cover of a recently produced, glossy overview of the worldwide Confucius Institutes movement, a Chinese girl is shown standing and leaning down towards a seated, smiling western boy, whispering something in his ear. The intended message is clear: Confucius Institutes promote friendship and communication. But there seems to be a subtler underlying message at work as well: we stand, you sit; we speak, you listen.

Seen in this light, Boris’s call to the nation to learn Mandarin becomes more interesting. Where should the nation go to do this? Confucius Institutes are definitely a good option for potential learners. There are many of them around, they are well funded, they are aimed at promoting Chinese language learning, and they have dedicated textbooks aimed at English speakers wanting to learn Mandarin.

For anyone wanting to obtain basic communicative skills in the language, the “soft power” agenda is not particularly relevant. The ability to say “please buy British” with a decent accent and without having to rely on Google Translate is more important.

In fact, if you type “please buy British” into Google Translate, it offers you the “translation” qing goumai Yingguo, which actually means “please buy Britain.”

Cynics might claim this is exactly what Boris and his delegation were asking their Chinese counterparts to do, but those having taken a few Mandarin lessons will know that the distinction between a noun and an adjective is not always clear-cut in Chinese. Yingguo ren is “British person” but Yingguo zhizao is “made in Britain”.

For some, the disadvantage of Confucius Institutes might be that many of their teachers have been trained, and their teaching materials developed, in China, where a different pedagogical culture prevails. There should be, within Boris’s agenda, a recognition of the need to develop more Chinese-language teaching material for all levels in this country as well, in order to offer learners a variety of options. And, indeed, to train more teachers of Mandarin, including non-native speakers of the language who can serve as role models.

At some point down the line, this is going to require reinvestment in languages, especially in teacher training programmes at university level, which are currently entirely unfunded by the government just like the rest of the humanities and social sciences. It is this mixed message coming from the government (“yes, languages are really important to our economy,” buy “no, language training should not be funded by the tax payer”) that has many in my field perplexed.

Chinese and English are vastly different languages. Becoming proficient in Chinese is not easy, especially if one also wants to learn to read and write - although writing has become a lot easier with the aid of computers.

English speakers struggle with Chinese pronunciation as much as young pupils all over China struggle with the sounds of English. Jonathan Stalling’s brilliant poem Yinggelishi, written entirely in Sinophonic English, is a good example of the difficulties involved. Yet the Chinese experience with English shows that, given time, effort, and significant government investment, it is possible to promote widespread bilingualism in these two languages. If Boris can help bring this about, I might even vote for him next time.