An influential US blog about climate change recently featured the story of a “brain-eating” infectious parasite that has caused 31 deaths in that country in the past decade.

“Brain-eating” is just one of the many phrases about germs, viruses and parasites that invoke terror. Think “flesh-eating” streptococcus, “muscle-dissolving” microbes, and the Black Death. They all have the medieval overtones of divine retribution.

If retribution is indeed any part of this particular resurgent infection, then it’s surely because the parasite’s rise is in response to humankind’s role in the warming of the planet. Warmth is, as you will see, vital to this lucky little parasite.

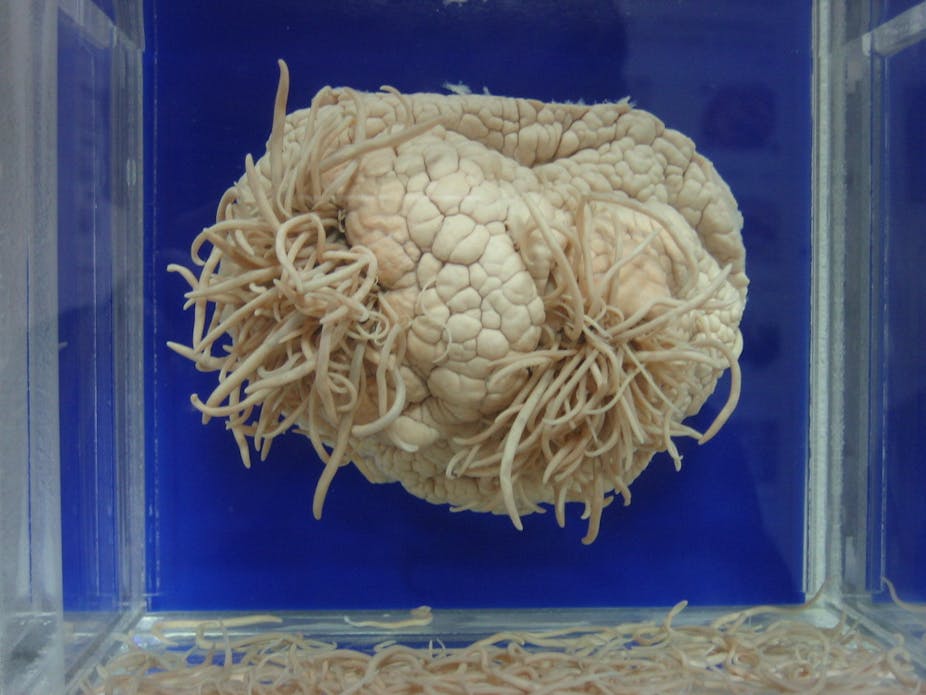

The infectious agent is a single-celled amoeba called Naegleria fowleri. It lives around the world, typically in warm freshwater lakes, rivers and hot springs, and thrives best at higher temperatures, up to 46 °C.

Humans become infected when the amoeba enters the nose during swimming, showering or other water-related activities. Once in the nose, the amoeba can travel to the brain, via the olfactory (smelling) nerves, and cause severe primary meningo-encephalitis (an acute inflammation of brain tissue).

Antibiotic treatment is rarely successful, especially if treatment is delayed, and the brain-destroying infection is usually fatal within ten days.

Loving the warmth

In Australia, this microbe occurs naturally in the Northern Territory, where most cases occur after visits to a swimming pool, freshwater lake or pond. But the amoebae sometimes cause problems elsewhere too.

Infections in South Australia and Western Australia in the 1970s were attributed to solar-warmed water arriving via long-distance overland pipes. Naegleria fowleri thrived in this warmth, and both states now monitor their reticulated water systems carefully.

Might this warmth-loving infectious agent establish itself further south in Australia as climate change proceeds? We should presume this will be the case.

The general expectation among researchers armed with some early observations is that regional warming will foster the spread of many infectious agents, especially via the movement of the mosquitoes, ticks or fleas that carry some of them.

There are widely-shared concerns about future increases in major killers such as childhood diarrhoeal diseases, cholera, malaria and dengue fever.

Several water-borne infections have shown recent associations with warming water, including water-snail transmitted schistosomiasis in eastern China and cholera outbreaks in Bangladesh when El Niño events warm the coastal waters.

On the move

Many species are already responding to recent warming. Marine species are moving polewards to maintain temperature constancy. In fact, they’re moving about ten times faster than land-based species – 70 kilometres versus six kilometres per decade.

Indian Ocean seabirds have shifted their territory further south. Various molluscs and coastal fish off south-eastern Australia are also shifting south. And North Sea cod have edged north towards Arctic waters, responding to regulatory sensors in their livers.

On land, animal, insect and plant species are relocating to higher latitudes and altitudes. In England, many birds and tiny creatures (butterflies, insects, and others) have extended their territories further north.

Warming in North America has enabled the devastating pine beetle to range further north and higher in the mountain ranges, killing off vast pine-tree forests that then fuel heat-amplified wildfires – another of interconnected nature’s typical cascade effects.

Similar moves are perceptible around Australia. In the Snowy Mountains in New South Wales, the pygmy possum and corroboree frog are under pressure as temperatures rise, snow-cover thins, and ski fields encroach on their habitats. Already living on the mountain top, those animals can migrate no higher.

[Various bird species](http://www.publish.csiro.au/journals/emu](http://www.publish.csiro.au/journals/emu), including migratory birds, have shown shifts in range or seasonal migration. But the good news is that warming in northern Tasmania is apparently enabling production of good pinot noir.

How to respond?

Much of this biological response to warming occurs out of sight, in the hinterland.

But there’s something more intensely tangible and shocking about a “brain-eating” amoebic infection in our immediate environment. It underscores the need for more extensive monitoring of climate-sensitive carriers of illness and infectious microbes, with better integration between jurisdictions and countries.

Human population growth and material consumption are making the world a riskier place in which to live. We ought not be surprised by brain-threatening and other unpleasant consequences such as this.

Rather, they should serve to alert us to the many unwelcome surprises that lie ahead – unless we use those brains to change society’s course, quickly.