The Orwellian dystopia of Doublespeak is very much in vogue right now thanks to concerns over Trump’s use of “alternative facts”. But alternative facts are just the tip of a dystopian iceberg that owes more to the soft brainwashing technologies of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World than it does to 1984’s harsh Stalinist oppressions and propagandist trickery.

To grasp the Huxleyesque nature of current events we need see them as part of a culture increasingly pervaded by the ideas of neuroscience – what I have termed neuroculture.

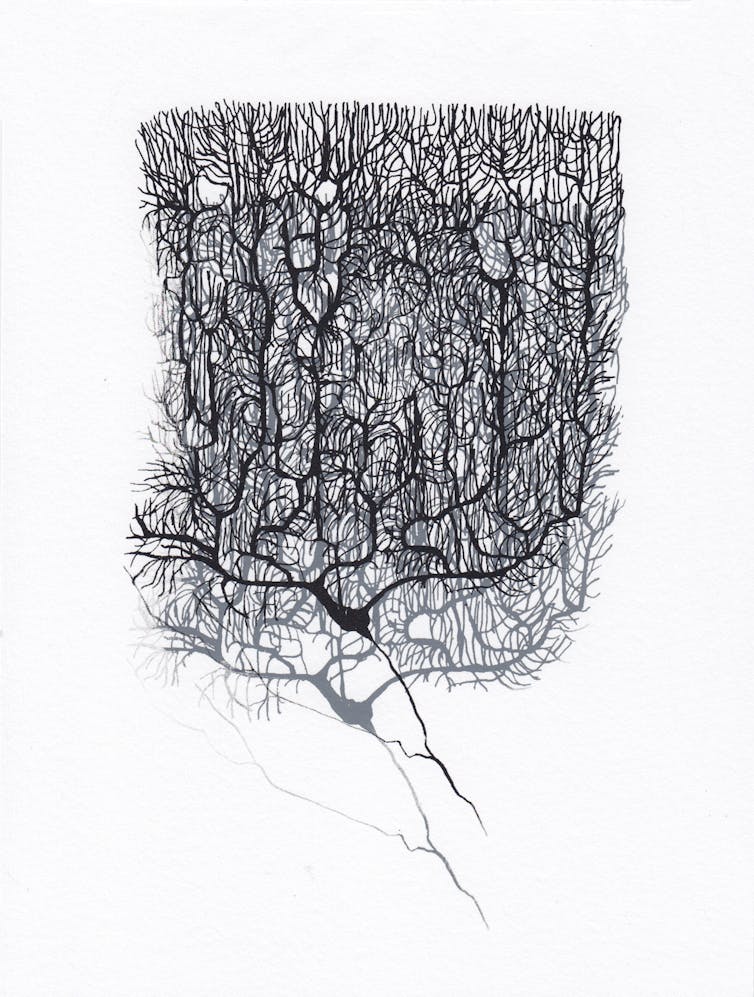

The origins of neuroculture begin in early anatomical drawings and subsequent neuron doctrine in the late 1800s. This was the first time that the brain was understood as a discontinuous network of cells connected by what became known as synaptic gaps. Initially, scientists assumed these gaps were connected by electrical charges, but later revealed the existence of neurochemical transmissions. Brain researchers went on to discover more about brain functionality and subsequently started to intervene in underlying chemical processes.

On one hand, these chemical interventions point to possible inroads to understanding some crucial issues, relating to mental health, for example. But on the other, they warn of the potential of a looming dystopian future. Not, as we may think, defined by the forceful invasive probing of the brain in Room 101, but via much more subtle intermediations.

Soma

Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) is about a dystopian society that is not controlled by fear, but rendered docile by happiness. The mantra of this society is “everybody’s happy now”. As Alex Hern argues in The Guardian, Huxley presents a more relevant authoritarian dystopia to that of 1984, one that can still be “pleasant to live in for the vast majority, sparking little mass resistance”. The best dystopias are often dressed up as utopias.

It is Huxley’s appeal to emotional conditioning that most significantly resonates with today’s dystopian neurocultures. He noted the clear advantages of sidestepping intellectual engagement and instead appealing to emotional suggestibility to guide intentions and subdue nonconformity.

As such, to achieve its goal, the society of Brave New World combines two central modes of control. First, the widespread use of the joy-inducing pharmaceutical, Soma, and second, a hypnotic media propaganda machine that works less on reason than it does through “feely” encounters.

Today’s neurocultures correspond to these technologies in conspicuous ways. To begin with, the rise of neuro-pharmaceuticals, like Prozac, have drawn attention to a growing societal need for self-medicated happiness. But equally alarming is the rise in prescriptions for ADHD treatments, like Ritalin, which control attention while simultaneously subduing difficult behaviour. The ADHD child’s mental state is a kind of paradoxical docile attentiveness.

The College of Emotional Engineering

Comparisons can also be made between Huxley’s College of Emotional Engineering and contemporary social media. In his book, the college is an important academic institution found in the same building as the Bureaux of Propaganda, with a unique focus on emotional suggestibility. This is where the feely scenarios, emotional slogans and hypnopedic rhymes are written. This kind of propaganda is for mass media consumption, but today’s emotional engineering takes place in far more intimate and contagious arenas of social media.

For example, in 2014, Facebook took part in an experiment designed to make positive and negative emotions go viral. Researchers manipulated the news feeds of over 600,000 users in an attempt to make them pass on positive and negative emotions to others in their network.

The idea that social media acts as a vector for both positive and negative emotional contagions might help us to rethink Trump’s ability to seemingly tap into certain negative feelings of disillusioned US voters. Certainly, the contagion of fake news is typically a poisonous concoction of fear and hate. But much of the populist appeal of Trump (and Brexit) has perhaps played on more joyful encounters with celebrity politicians than those experienced with the dry intellectual elites of conventional politics.

Roses or orchids?

The pervasiveness of today’s neuroculture started with the neuroscientific emotional turn in the 1990s. Scientists realised that emotions are not distinct from pure reason, but enmeshed in the very networks of cognition. The way we think and behave is now assumed to be greatly determined by how we feel.

The seismic influence of this profound shift has extended beyond science to economic theories concerned with the neurochemicals that are supposed to affect decision making processes. It also underpins new models of consumer choice focused on the “buying brain”. The advent of neuroeconomics, followed by neuromarketing, has resulted in further spin-offs in product design and branding informed by emotional brain processing. The consumer experience of a brand is now measured according to the frequency of brainwaves correlated with certain attentive and emotional states.

Perhaps there’s nothing new in neuroculture. Advertisers have been trying to infect feelings since the advent of advertisements. Similarly, politicians have been kissing babies for affect since the age of the crowd. Maybe my idea of neuroculture is an example of what has been cynically termed neuro-speculation. But in an age hastened by social media and self-medication, there is a dystopic intensification of infected and manipulated feelings that cannot be ignored.

Not everyone agreed with Huxley’s predictions of a neuroscientific dictatorship. One literary critic once compared him to a rabbit going down a hole only to think all the world was dark.

But it was the attention he received from scientists that should alert us to the profundity of his dystopia. In particular, the 20th century scientist Joseph Needham argued that scientific knowledge is not immune to political interferences. Needham called Huxley’s Brave New World an “orchid garden” – a demonstration that scientific knowledge does not always lead to a bed of roses. Huxley, he noted, helps us to “see clearly what lies at the far end of certain inviting paths”.