Who would you choose as Britain’s most influential living film director? Ken Loach? Mike Leigh? Even Sam Mendes, director of the current Bond film, Spectre? For my money, it would be Peter Watkins, who celebrated his 80th birthday on October 29.

Perhaps you have never heard of Watkins, nor seen any of his films. Yet he pioneered making dramatic reconstruction look like gritty documentary reality, influencing everyone from Loach and Leigh to Paul Greengrass, director of the Bourne films. The dozen films Watkins made over his 40-year career remain some of the most powerful and politically challenging of all time.

Born in Surrey, he began in amateur filmmaking in the late 1950s. His professional debut was Culloden for the BBC in 1964 – retelling the story of the last land battle on British soil. It was hailed as a breakthrough for the way it used handheld newsreel-style shooting and direct-to-camera “interviews” with participants such as Bonnie Prince Charlie, as if television had been around in 1746.

But Watkins was doing more than finding new ways to make audiences take notice. He was also exposing how “reality” in television and film could be manipulated. If a documentary style could be convincingly faked in Culloden, what about other films and TV programmes that showed the world “as it is”? This was years ahead of its time.

Fall-out

For Watkins’ next film, he aimed to bring the future to life in the same way as Culloden had done with the past. The results were incendiary. The War Game (1965) offered a stark “pre-construction” of what might happen if the UK was hit by a nuclear attack. The images were so disturbing – harrowing firestorms; emaciated bodies; the breakdown of civil society – that the BBC imposed a ban on it for 20 years. It was a notorious act of censorship, recently revealed to have been imposed in collaboration with the British government. Watkins had the last laugh when the film won an Oscar in 1967 for Best Documentary Feature. By then, he had left the corporation. His subsequent work is arguably even more interesting.

Watkins’ first feature film, Privilege (1967), imagined a dystopian future in which a British “coalition government” creates a pop star it can manipulate to control the young (played by ex-Manfred Mann singer Paul Jones). It received mixed reviews on release but has since been seen as prescient of our Simon Cowell-era of manufactured pop.

Disappointed with the reaction to the film and the continuing fall-out over The War Game, Watkins took the crucial decision to leave Britain in 1968. The most international of all British-born directors, he would go on to make films in various countries, always in the native language.

First came The Gladiators (1968), shot in Sweden. Together with his US-produced Punishment Park (1971), it largely pioneered the futuristic “violence as game” scenario of participants fighting to the death for the pleasure of a TV audience. You can see the huge impact on science fiction in the likes of Rollerball (1975/2002), The Running Man (1987) and the current The Hunger Games franchise. With their devastating critiques of how the mass media can manipulate real suffering for entertainment, Watkins’ films also predicted the rise of reality TV.

Meanwhile, he was influencing some of the most famous names of the 20th century. In 1969 John Lennon and Yoko Ono cited him as the primary influence for their celebrated campaigns for peace. The previous year, Watkins had written a long letter to hundreds of opinion-formers asking what were they doing to work for world peace. According to Lennon, it was like receiving your “call-up papers for peace”. “Bed-Ins”, “Bagism”, “Give Peace a Chance”, “Imagine” – would these have happened without Peter Watkins?

Another famous stunt also carried Watkins’ trace marks. When Marlon Brando refused his Best Actor Oscar for The Godfather in 1973, he sent a young Apache woman to the ceremony to protest Hollywood’s depiction of Native Americans. This was after he had collaborated with Watkins on an aborted film about General Custer and The Indian Wars.

Munch

In the early 1970s Watkins decamped to Scandinavia again to make what many regard as his masterpiece, Edvard Munch (1973). This biography of the famous Norwegian painter was shot in Watkins’ trademark documentary style. He identified so strongly with Munch that he invested many of his own feelings in the portrayal, which helps explain why it is so good. Ingmar Bergman, Sweden’s greatest filmmaker, reportedly said “the film was made by a genius”.

Watkins continued working until the end of the 1990s, culminating in La Commune (Paris 1871) (2000). This re-told the events of the 1871 Paris Commune, where Parisians mounted barricades on the streets to protest their hated National Government, only to be slaughtered by its troops.

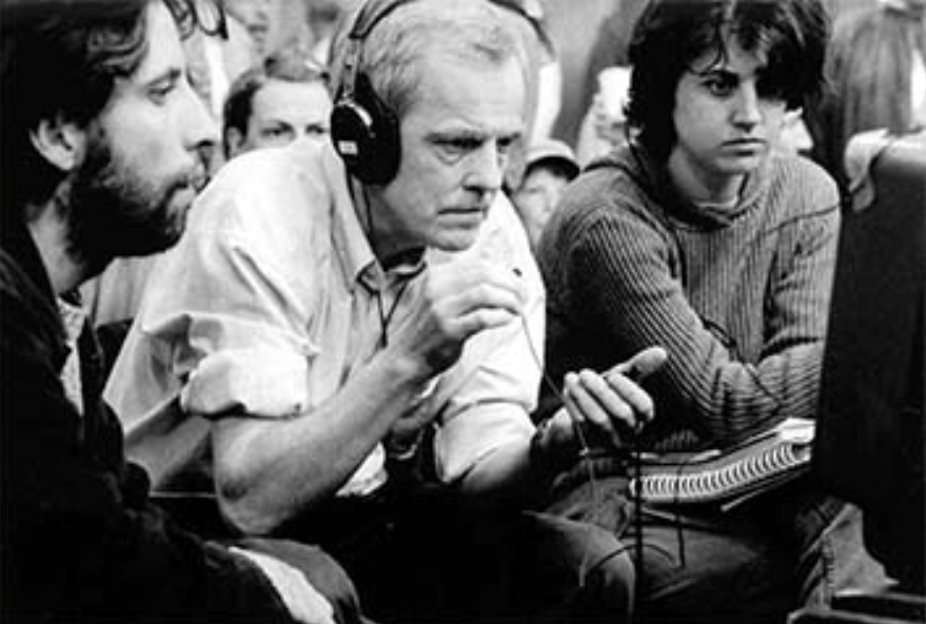

I had the immense privilege of being invited to the eastern Paris studio along with a colleague to witness the shoot. Watkins shot for three hot weeks in July, reconstructing the commune with the help of 200 French people who were not professional actors. He shot in a series of long takes with minimal editing, aiming to provide a space for this cast to express their political feelings not only about the historical events but to draw the link with society today. Suddenly and thrillingly, characters in 19th-century costume were discussing contemporary issues such as racial discrimination, and the power of TV, radio and the internet. Critics rated La Commune among Watkins’ greatest works, voting it one of the best films of the 2000s.

Watkins is now retired in France, posting periodic updates on his website about what he sees as the “media crisis” in the world today. His work has seen a major re-evaluation by a new generation, including career retrospectives at the likes of Harvard and the Tate Modern. He is indisputably Britain’s greatest film dissident. Happy 80th birthday, Peter Watkins.