By cutting through the buzz and spin surrounding the federal budget, The Conversation’s budget explainers arm you with the key terms and facts needed to understand the budget and what it means for you.

There have been recent claims that Australia’s government debt is growing more rapidly than any other developed economy.

Is this correct? Surely Australia can’t be worse than Greece when it comes to government debt? In order to understand the argument in reports such as these it is important to understand the difference between government deficits and public debt, and also between gross and net numbers.

Each year in May the Federal government brings down its budget. The budget outlines all of the Federal governments projected spending and revenue for the coming financial year. It is never the case that the government spends exactly what it raises in taxes, so in any given year there is either a budget surplus (tax revenues are more than spending), or a budget deficit (tax revenues less than government spending).

In addition the States bring down budgets once a year, and so the government sector as a whole will normally run budget deficits and need to borrow to cover these deficits, though in some recent years the government sector as a whole has run surpluses.

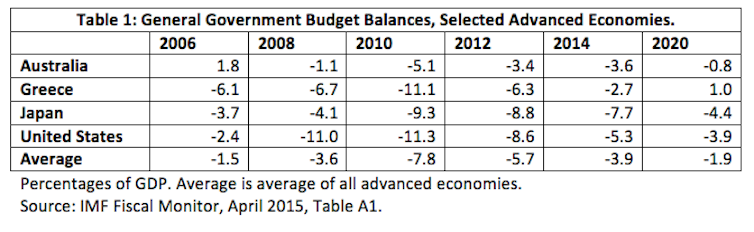

Table 1 shows the data on government budgets and deficits for selected advanced economies, as reported by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). It also includes a forecast for 2020. The data is reported in terms of percentages of GDP, which gives a picture of the size of government deficits and surpluses relative to the size of the economy. In Australia, the budget was in surplus in 2006. The Federal government ran budget surpluses every financial year from 1996/97 to 2007/08. The surplus peaked at $28.1 billion in the last of these years.

Australia was unusual among advanced economies in running budget surpluses prior to the global financial crisis, with the average advanced economy having a deficit of 1.5% of GDP in 2006. As can be seen from Table 1, Greece had a very large budget deficit in 2006, but so too did Japan and the United States.

Governments are no different to an individual or family. If you spend more than you earn then you will need to draw down your savings, or borrow if you do not have any savings.

Countries that run budget deficits are in this position, while countries that run a budget surplus will be able to pay down debt, or build up assets if they do not have any debt. As Australia’s Federal government started to run surpluses in 1996/97 the government’s debts started to decline. Federal government debt fell steadily from a peak of $111 billion in 1996/97 to the point where debt was extinguished in 2005/06. However, here it is important to note the difference between gross and net debt.

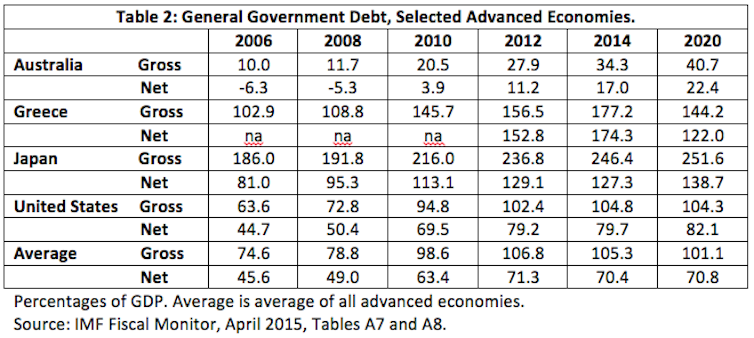

In 2005/06 the Federal government did still borrow. The government decided that they needed to issue government bonds as these were deemed to be important to the efficient functioning of financial markets. The proceeds of these bond issues were put to work in the Future Fund. The result was that gross debt was still positive, but net debt, once these financial assets were subtracted from gross debt, was negative (a negative debt position is the same thing as an asset position). In other words, the government still had (gross) debt, but they also had significant financial assets, so that the net debt position was negative.

Table 2 shows the comparison of net and gross debt across selected advanced economies in recent years. It is very clear that compared with these peer economies Australia’s government debt levels are very low. The commitment by both sides of politics since the mid-1990s to stabilise and reduce debt resulted in gross and net debt levels reduced to well below advanced economy averages. The problems which Greece continues to have with its debt can be traced back to large deficits and high debt levels for more than a decade.

It is notable that Australia’s debt levels, while rising, remain well below debt levels in other advanced economies. In 2014, net debt in Australia was 17% of GDP, compared with 79.7% in the United States. So the rise in debt in relation to GDP by 5.4% by 2020, even if it is the worst among advanced economies, still puts Australia in an enviable position relative to its rich country peers. According to the forecasts Greek debt will have fallen by almost 50% of GDP, but their net debt will still be three times the level of Australian debt.

So should Australia’s government be concerned at our rising debt levels when both gross and net debt levels remain low?

In my view they should. The budget and debt levels present a snapshot of the financial position of the government in any given year, but as the Intergenerational Report shows, this snapshot does not account for significant future liabilities due to an ageing population. Many other advanced economies are likely to be weak into the indefinite future because of weak demographics and poor government finances.

Our government needs to ensure we do not go down the same road. It needs to stabilise our government balance sheet while it is still possible to do so.

Read other federal budget explainers here.

This story has been altered since publication to correct errors introduced during the editing process.