While the Abbott government’s first budget has been widely criticised for its aggressive cost-cutting measures, the largest single reduction – a A$7.6 billion cut to Australia’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) budget over the next five years – has been met with far less public concern.

A poll taken in the wake of the budget found that almost two-thirds (64%) of those surveyed supported the massive cuts to foreign aid, making it the most popular saving measure announced.

There was genuine public angst over the budget’s implications for pensioners, those with disabilities and those on welfare payments. In this sense, the response to the budget indicated that Australians are concerned about the impact of budgetary measures on vulnerable people – as long as they are Australian.

But while the image of Australia as a “good international citizen” still rings true for many Australians, our treatment of vulnerable outsiders, whether the impoverished or the oppressed, suggests otherwise.

The hits to aid keep coming

Since the then-Rudd government announced that Australia would double its aid program by 2015-16 to reach 0.5% of its Gross National Income (GNI) in 2007, Australia’s aid spending has taken a series of hits. In successive budgets in 2012 and 2013, the targeted spend on aid was delayed, saving the government billions.

Days before the 2013 election, the Coalition made clear its plans to reduce Australia’s aid spending by $4.5 billion over four years. Days after the election, prime minister Tony Abbott announced that AusAID Australia’s aid agency, AusAID, would be “integrated” within the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Both of these moves were concerning for aid organisations. The former was a departure from a bipartisan commitment to lift aid spending to 0.5% of GNI.

Despite these developments, the extent of the cuts released in the budget surprised many. The government announced that $7.6 billion would be saved through capping the aid budget for two years, allowing aid to grow in line with the consumer price index (CPI) only from 2016-17, and cutting $2 billion in 2017-18. In real terms, this amounts to around a 10% reduction in aid spending from 2013 levels.

Is Australia no longer a good international citizen?

While the cuts are problematic enough for recipients of Australian aid, it also does little for our reputation in the global community.

Australia’s aid budget has fallen well short of that of other OECD states, including some of those states hardest hit by the financial crisis. In 2013, for example, the UK reached the UN-recommended 0.7% target of GNI on aid spending, making it one of only five countries to do so.

The make-up of Australia’s aid budget also suggests Australia is failing in its moral obligations to the most vulnerable. The language of Australia’s aid program has increasingly emphasised its role in advancing Australia’s economic and strategic interests rather than achieving goals such as poverty alleviation.

Aid to the world’s poorest countries in sub-Saharan Africa will be reduced by around 25% from 2013-14 to 2014-15. Increased aid to Papua New Guinea was part of a deal struck when PNG agreed to house asylum seekers in the Manus Island detention centre.

Explaining the silence on aid

Despite the nature of the changes to Australia’s foreign aid program, other issues dominated the post-budget headlines and, as polling suggests, the concerns of the broader population.

A range of pragmatic political factors could help explain the relative silence on aid reductions. In reducing aid commitments in its final two budgets before the 2013 election, the ALP had ultimately made aid reduction bipartisan. As a result, mobilisation on this issue by Labor, now in opposition, was unlikely.

There is also a case to be made that aid reductions didn’t violate the government’s pre-election promises in the same way that other issues had. It certainly didn’t constitute a “new tax”. But this doesn’t explain why some Australians ultimately support the move to reduce aid, particularly to the tune of $7.6 billion.

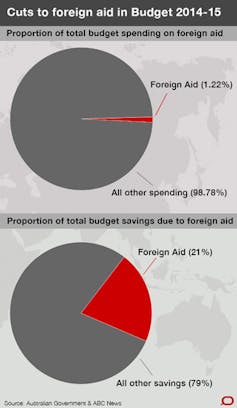

A large part of the problem may be ignorance. Australians have a limited awareness of our aid programs – what they are for, where they are targeted and how much we give. In a 2011 Lowy Institute survey of public opinion on aid, those surveyed on average estimated that overall spending on aid constituted 16% of government spending, compared to the real level of 1.3%.

Without a sound public understanding of the function of aid expenditure, the case for maintaining or increasing levels of funding becomes harder.

A more concerning interpretation would focus on the absence of concern for the rights and needs of vulnerable outsiders. Australia’s international commitments do not tend to feature prominently in elections, and when they do it tends to be in favour of governments looking to wind them back. This would seem evident in relation to asylum seekers and climate change, for example. Aid could be the latest foreign policy issue viewed through the lens of domestic considerations.

Leadership is sorely needed to make good on Australia’s international obligations, advance Australia’s reputation and make a case for change to a sceptical public. But when it comes to foreign policy, leadership in Australia appears to be in short supply.