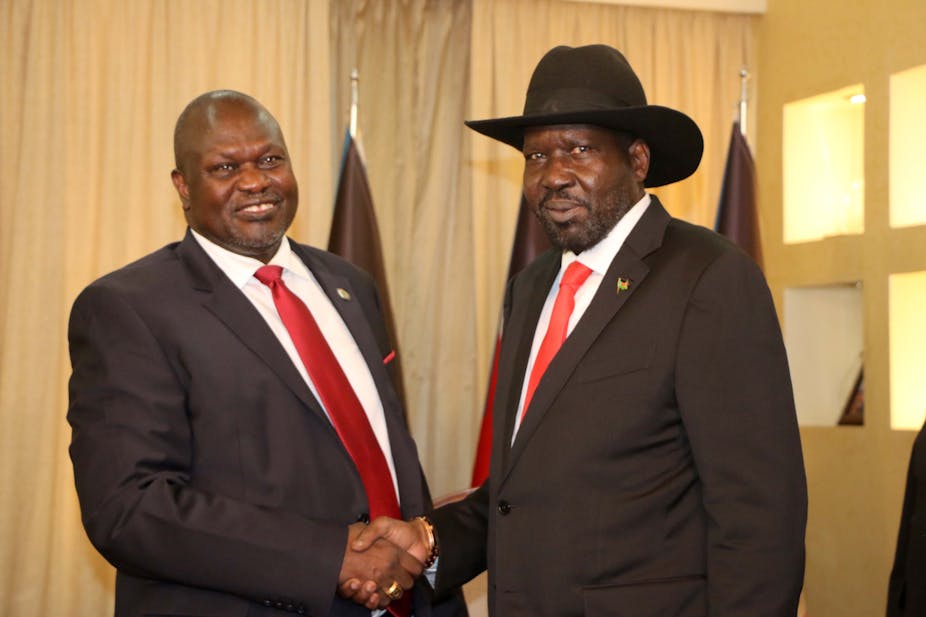

South Sudan’s parties have achieved some milestone agreements recently. This includes a 100-day extension for the formation of a transitional government of national unity, and a roadmap to peace.

The world’s newest country has been besieged by a nearly six-year civil war that has cost nearly 400,000 lives. Often eclipsed by news of conflicts in Syria, Yemen and Afghanistan, the civil war in South Sudan has been a humanitarian disaster of epic proportions.

The commitment of the key parties — the government of South Sudan and four opposition groups — to the “revitalised” peace accord signed in September 2018 remains in doubt.

Is it possible to turn this doubt into optimism?

We believe so, but only under certain conditions. Under the University of Notre Dame’s Peace Accords Matrix we have been tracking the progress of three dozen comprehensive peace agreements around the world. One of them is the pact agreed in South Sudan.

Our data shows that the key element of successful accords is the political will to quickly implement key trust-building provisions. At the top of this list is security measures.

Based on this insight, we would argue that the international community must not insist on a deadline for a unity government before a number of key steps have been taken. These include the completion of the training and unification of the armed forces, the establishment of the VIP protection force, and agreement on how many states there will be and where their boundaries should lie.

Tracking progress

We have found through our research that successful agreements are not “disempowering”. What we mean by this is that no single party should be the sole beneficiary of the agreement.

In the case of South Sudan, the issue of security arrangements stands out. Had provisions for these, as well as border demarcations and number of states, been agreed and implemented immediately, trust could have developed between the warring parties and the war weary population. The nascent trust, in turn, would have diminished some of the fears related to security without disempowering any of the parties.

One of the reasons this hasn’t happened is the way in which the monitoring and evaluation commission was established. All the parties to the agreement participate in the monitoring mechanism, but it lacks the political mandate to resolve implementation problems. This is reflected in the parties’ missed deadlines under the agreement.

Earlier this year, as the May 2019 deadline for the formation of the new transitional government of national unity approached, there was a clear lack of political will to reach out to the other parties. If preemptive steps like ongoing dialogue had been taken, problems could have been addressed before they became roadblocks.

Our analysis was consistent with reports from South Sudan, the Reconstituted Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission and other sources, suggesting the signatories had almost completely failed to take even basic steps to demonstrate their commitment to the September 2018 agreement.

South Sudan’s religious community, civil society leaders and external actors lobbied the government and the opposition parties strongly to implement the peace accord. This led to the signatories agreeing to a six-month extension with November 12, 2019 as the new deadline for the formation of the new government with the appropriate security measures in place.

Days of inaction in May soon turned into months of no progress. None of the parties made any serious efforts beyond maintaining the ceasefire. In the last month, however, bottom-up pressure and international persuasion from a number of countries and organisations produced some activity.

Nonetheless, data demonstrate that fundamental elements of the accord – such as creating a united national army – have barely budged from “no activity” to a “minimal” level of adherence.

What’s needed

Our research findings are in line with the recent statement by the South Sudan Catholic Bishops’ Secretariat. This is that it is more important for the parties to implement the agreement fully, with ownership on all sides, than to meet a deadline.

Pushing the parties to selectively implement the unity government provision when the necessary security reforms are not in place could prove deadly. This is what happened the last time in August 2016.

The 100-day extension agreed to on November 7 allows the five signatories much-needed time to build mutual trust and confidence. But they must do so through continuous face-to-face meetings with each other where they can discuss and resolve implementation challenges.

Witnesses to the peace accord, particularly the Troika (the US, the UK and Norway) and the UN, must unite behind the terms stated in the most recent communiqué and encourage the parties to engage in an ongoing political dialogue.

In addition, they must jump-start the stalled peace implementation by finding the space for a retreat, as called for by the South Sudan Civil Society Forum. This will enable the signatories to conduct continuous meetings to develop and implement the peace roadmap and accountability mechanism. And they must hold the parties responsible for any failures of implementation.

Clearly, every effort must be made to accomplish all of the pre-transitional tasks as quickly as possible. But even more importantly, the international community must insist on continuous, active dialogue between all parties to the accord. A mechanism to include non-signatories to the agreement must be found, as noted by the EU following the recent political dialogue by other South Sudanese hosted by the religious community of St. Egidio.

This must be accompanied by a timed, realistic implementation plan with consequences attached for failure.

Under these conditions, we believe that the parties can end the devastating war in South Sudan and create the essential foundations for a functioning state.

Success, of course, is also conditional on South Sudan’s political and military leaders making good on the promises they made – promises upon which the future of their country depends.