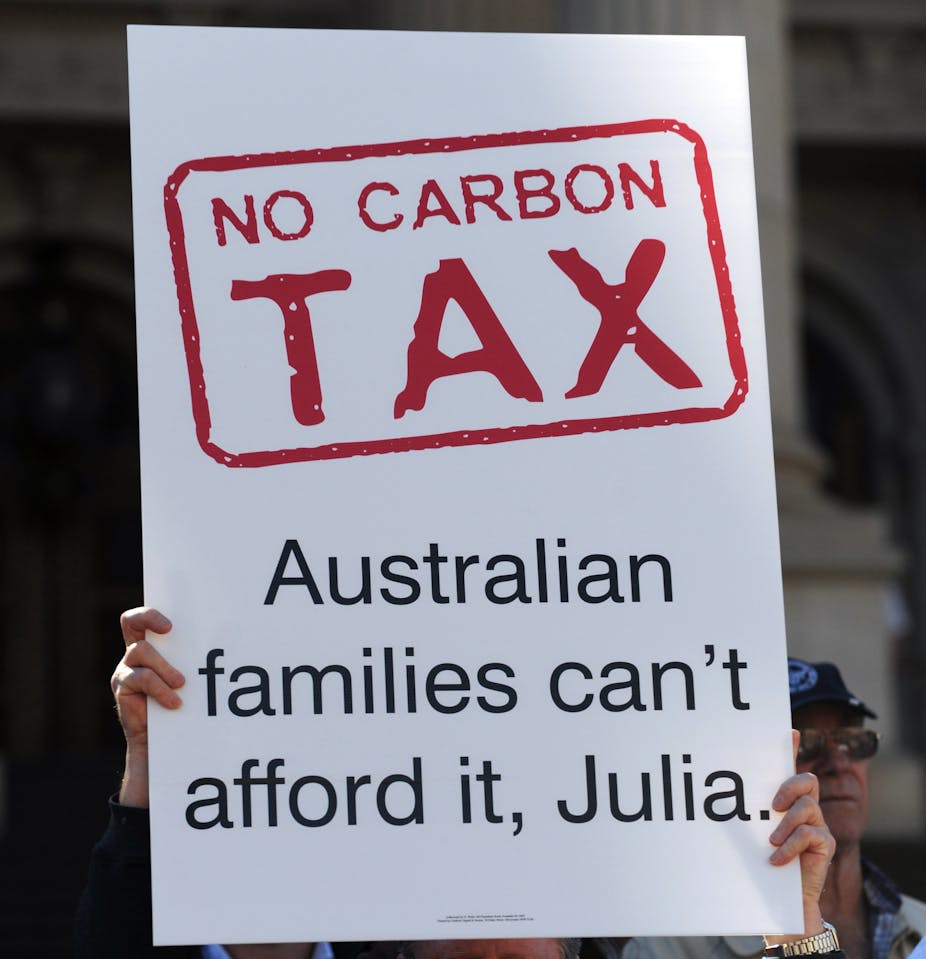

When we read that a carbon tax will hit the average hip pocket, should we worry? Will the ETS push us all into penury? And will it make any difference to our emissions at all?

Can we know the cost to households?

Certainly if you’re prepared to define the program in enough detail, then you can estimate the additional cost for householders, but of course it’s only an estimate because every household has different consumption patterns.

The figures you see in the media can be misleading in the sense that very few households in the country will suffer a cost of exactly the figure mentioned in headlines. But these estimates are useful as an indication of the broad magnitude of the effects of the ETS.

They are also potentially misleading if people think they’ll be worse off by that amount. Part of the proposed scheme involves compensation to low and middle income earners.

The overall effect on many households would be very much less than the published figure, and in some cases it could be zero, depending on the specific compensation systems that are put in place.

The idea of paying compensation is consistent with what economists have recommended should be done with the proceeds of a carbon tax. The idea is to substitute it for other taxes, so that the scheme is revenue neutral, but we are taxing “bads”, like pollution, rather than, say, income.

But doesn’t compensating people defeat the purpose?

I’ve heard this sort of comment in the media, but it’s a complete furphy. It reveals a misunderstanding of how the scheme would work.

In an effective emissions trading scheme, the level of emissions is determined by the number of permits that are issued. Paying compensation makes no difference to this. People are still required to change their emissions to operate within the official limit.

The point of compensation is to ensure that certain groups in society are not unfairly disadvantaged, and to win political support for the scheme.

So you can compensate people and still fully influence their behaviour.

Can consumers avoid the extra costs?

To some degree, yes. One of the objectives of the exercise is to encourage people to move their consumption away from goods that are associated with high carbon emissions onto goods that are associated with low carbon emissions.

If people do respond, then they could avoid at least some of the extra cost due to the carbon price. Of course, avoiding those costs may result in other costs, such as loss of convenience or missing out on the pleasure of a good that you would otherwise have bought.

Some products have high carbon footprints, others much less so. That will be revealed to consumers by the relative price increases of different products.

How will we feel the effects of pricing carbon?

I expect that there will initially be an effect on people’s psyche, when they see price increases for some goods but not others. It will raise awareness of the emissions associated with different products and services.

The proposal is for the price of permits to be fixed at a fairly low level initially, and the fixed price will probably increase slowly over time, leading up to the floating of the price after a few years.

Individuals won’t be buying and selling emissions permits. That will be for larger businesses. For most people, the impact they can see will be through higher prices of goods whose manufacture required high emissions.

After the permit price eventually is floated, businesses will likely be affected by a degree of volatility in the price, in response to ups and downs in the economy. They may wish to hedge the price in order to avoid the sort of price volatility that we’ve seen in the European emissions trading scheme.