Until this week’s tax credits debacle, the Conservatives have performed exquisitely the role of the reasonable and pragmatic English party that swears by its faith in “whatever works”.

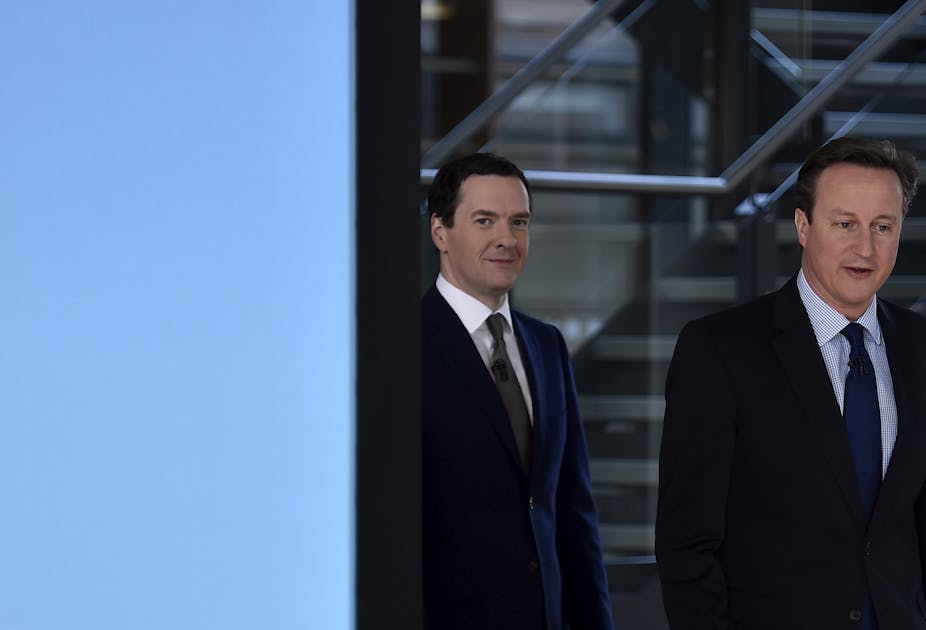

So far, under the leadership of David Cameron (though the chancellor, George Osborne, can claim the role of co-author), the Conservatives have done a remarkably good job of presenting themselves as the guardians of the hard-to-define political centre ground. The party’s greatest achievement has been to dress an ostensibly right-wing agenda in the soft clothes of a well-meaning, reasonable and pragmatic centrism stripped of ideological excesses.

Cameron has recently claimed that the Conservatives as “the party of equality” and few quibbled with him. Similarly, when the chancellor said the Conservatives were “now the party of work, the only true party of labour”, he was mostly commended for his audacity.

But in reality, this move to the centre has been a mere rhetorical device to change the terms of the political debate. Hidden behind the centrist rhetoric lies an ideological Conservative agenda of reducing the size of the state and demonising the poor. This has been going on for quite a while.

Radical to the end

The 2008 financial meltdown and ensuing deficit crisis offered the Conservatives the opportunity to discreetly shed the compassionate conservatism of David Cameron’s earlier days and put forward a lean-state agenda. This was justified in the most reasonable terms; as Cameron told the 2009 party conference, the economy was “broken” because “government got too big, did too much and undermined responsibility”. Like a reckless housewife, the Labour government had maxed out the nation’s credit card.

And at the 2010 election, working on the principle that in politics perception is almost everything, the Conservatives managed to convince large sections of the media and their very eager coalition partners that a deficit reduction strategy based on draconian public spending cuts was not only necessary, but was above all a reasonable and pragmatic response to the crisis.

The fact that after five years of austerity measures the coalition government had only managed to halve the size of the public deficit almost did not matter.

In fact, it mattered so little that Osborne went on to commit the current government to deliver a £10 billion budgetary surplus by 2019-20. Needless to say, this goal is predicated on further cuts to public spending. However, there’s nothing centrist or pragmatic about defending budgetary surpluses as the main goal of economic policy.

A truly “commonsensical” politician would never make such a promise, because he or she would be aware that there are too many unknowns in politics to make such a commitment. And a truly pragmatic politician, one who believes in “what works”, would never sign up to a policy deemed economically illiterate by a strikingly large number of professional economists.

On the other hand, this is exactly the type of policy that a true believer in the economic virtues of monetarism and the small state would pursue.

Sharp edges

This radical agenda is detectable in the government’s approach to the welfare state. The party has draped its right-wing agenda in the mantle of the so-called compassionate conservatism or “Red Toryism”, claiming to be “the true workers’ party” and presenting the modest raise to the minimum wage in the progressive language of the national living wage – a rather dubious title.

In reality, the Conservatives have been consistently dismantling the welfare state since 2010. Just as the coalition government cut £17 billion from the welfare budget, the planned cuts to tax credits are not simply a means to achieve a budget surplus by 2019-20.

As even the Financial Times suggested, there are other ways of saving £4.4 billion a year. These cuts are ultimately about defending a conservative conception of the good society that sees poverty as the result of the moral choices of individuals.

In truth, Osborne’s rhetoric of “shirkers versus strivers” speaks of nothing so much as a Malthusian vision of the causes of poverty. That approach was equally apparent in the way the health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, justified the cuts to tax credits. According to him, those cuts were about sending “a very important cultural signal” and about promoting “dignity”.

It is also telling that Osborne has stubbornly decided to insist on these cuts despite the concerns of Conservative backbenchers with more pragmatic and compassionate dispositions.

It’s highly likely that the humiliating tax credits defeat in the House of Lords and the growing disquiet among Conservative backbenchers will force the government to sand the sharper edges off at least some of its welfare cuts. But any such recalibration will not be a victory for pragmatic centrism. Look past the language of pragmatism and common sense, and it’s clear that this government’s zeal to put forward a deep-blue Conservative agenda has not abated.