President Obama is eager to use the few remaining legislative days before the election to get some work done.

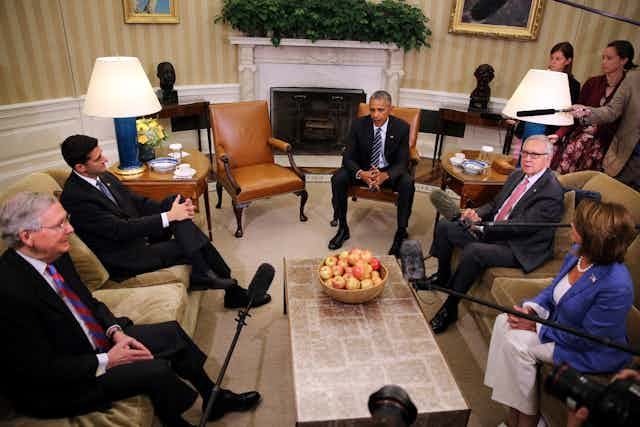

Congressional leaders met at the White House yesterday to discuss a funding package that would avoid a government shutdown on Oct. 1.

Many see Congress as frustratingly ineffective. Currently, fewer than one in five Americans approve of the job Congress is doing. Recent Congresses have struggled with productivity in terms of lawmaking. Members of Congress work on a limited schedule and spend more than half their time raising money.

The modern Congress leaves little time for legislators to become friends, which may contribute to their lack of willingness to work cooperatively with one another. Yet, one common type of organization on Capitol Hill may provide an antidote: caucuses. Officially, these groups are called “Congressional Member Organizations,” and a record of them can be found on the website of the House Committee on Administration.

Some caucuses are well-known and established, such as the Congressional Black Caucus, while others are thought of as trivial organizations. Some caucuses appear to primarily support legislators’ hobbies or personal interests, such as the Congressional Bike Caucus, Congressional Horse Caucus or the Congressional Bourbon Caucus.

In research I’ve done with Nils Ringe, we found how this understudied congressional institution plays a critical role in bringing members of Congress together.

Can caucuses help overcome divisions?

We have found that most caucuses are truly bipartisan, and more than three-quarters include members from both political parties. Most have a shared governance structure with one Republican and one Democratic cochair leading the group.

These groups value their bipartisan nature and make explicit choices to protect this characteristic. Many such caucuses will avoid taking positions on controversial issues, even when a bill may be directly relevant to the topic of the caucus. Caucuses will avoid taking stances on such bills if they suspect it will cause a rift in the membership along party lines. For example, the Congressional Caucus on Parkinson’s Disease avoids taking a stance on stem cell legislation. These groups prize having an institution that is designed to foster bipartisan communication and develop area expertise outside of the party and committee systems of Congress.

Some caucuses are explicitly partisan, however. These include the Democratic groups such as the Blue Dog Coalition, New Democrat Coalition and the Congressional Progressive Caucus and Republican-only groups like Republican Study Committee, Republican Main Street Partnership and House Tea Party Caucus. These organizations operate more like factions of the party with which they are associated, and represent less than 2 percent of all caucuses on Capitol Hill.

Congress now has more caucuses than it does members, and the list grows every year.

The current Congress hosts more than 400 official caucuses, and there may be a few hundred more that have not registered with the House Committee on Administration. The fact that these groups are voluntary and nearly free to participate in helps explain their popularity. Far from being trivial, our research shows that the growing network of connections formed by this mass of groups serves a social and informational benefit to Congress.

I have collected data on registered and informal caucuses and identified their members, and found a steady pattern of growth. The graph below shows that the number and size of caucuses has grown consistently since the early 1990s, even after Speaker Newt Gingrich rewrote the rules to defund and nearly ban caucuses in 1995. At the time, Republicans saw caucuses as a corrupt system of favoritism for pet Democratic causes. In response to these restrictions, outside organizations picked up the slack and the rules about establishing groups eased. Altogether, the changes created ripe conditions for groups to grow and many legislators began to reap their benefits.

Despite their growth, caucuses have no formal role in the legislative process. They cannot introduce legislation, hold hearings or conduct formal investigations. They operate as an informal, but prominent, feature of life on Capitol Hill.

So why does Congress expend considerable time and resources developing and maintaining this system of caucuses that have no authority?

An unofficial role

When interviewed, members of Congress and their staff gave all sorts of reasons for joining caucuses. Their answers span the gamut, from “I joined because a constituent asked me to,” to “I have a personal experience or connection to the subject,” to “I want to be a part of the conversation on this policy topic.”

Our research shows that there are two main consequences of joining caucuses. Legislators gain access to novel information about a particular policy, and they can develop relationships with legislators with whom they would not otherwise interact.

Much of this benefit and the robustness of the caucus system is due to support provided by outside interest groups, foundations and advocacy organizations, which also benefit from the existence of this system. Outside groups can help establish and maintain caucuses by providing and distributing valuable information from relevant industries or communities. In return, these groups gain a point of privileged access to a set of legislators who have voluntarily identified themselves as being interested in the topic. For example, the Fire Services Caucus has more than 250 members and is supported by the Fire Services Caucus Foundation.

It may seem like a set of groups like this – designed to foster relationships and information for the benefit of improved lawmaking – might contribute to reducing polarization in the House. However, our analysis of voting patterns over this period suggests this isn’t necessarily the case. Through dozens of interviews with Capitol Hill staffers, we learned that caucuses influence bills in the early stages of the legislative process, when ideas are being floated and slowly massaged into legislation through the formal channels of Congress.

At least, it seems unlikely that this system of caucuses makes things worse in Congress. Those who participate in the system appear to value it highly and draw benefits from it, even if it’s not making Congress more productive.