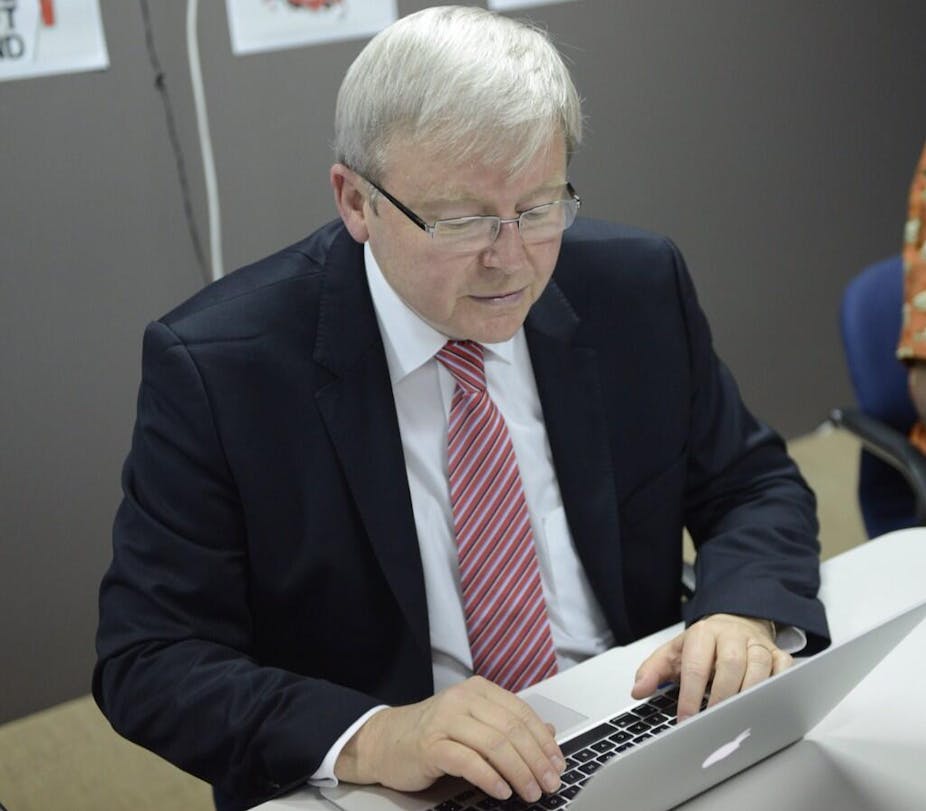

As journalism professor David Maguire noted at the start of this campaign, prime minister Kevin Rudd has had such limited time in which to develop a social media strategy that he has “parachuted” in some advisers from Barack Obama’s successful digital campaign.

But Rudd’s use of social media in this election will not be able to replicate the Obama campaign in the US, which recruited first-time voters and non-voters rather than the swinging voters of Australia’s compulsory electoral system. Obama had a longer lead-up to actually establish a relationship with these voters, and used sVRM (social voter relationship management) to engage voters in issues that are close to them.

In Australia’s compulsory voting setting, politicians must show they are at least keeping up with normality of social media but are largely using it simply as a broadcast channel. Opposition leader Tony Abbott and Rudd are posting their requisite one tweet a day, but microblogging sites like Twitter are so diffuse now that users don’t get any intimacy out of it.

So, how influential is social media for winning over votes in an election? Well, not very. For starters, Facebook and Twitter are not platforms for announcing policy, or building recognition from voters in anyway that trumps feeding mainstream media coverage. Rather, they are media in which followers of the parties and the leaders can register their support, and gain affirmation that they are part of a movement.

When high-volume tweeters like Christine Milne, Craig Emerson and Malcolm Turnbull tweet, it can be important for maintaining their following. But as Axel Bruns shows in his excellent analysis of Twitter trends, too many tweets per day can be a turn-off for followers who get overloaded.

Put simply, social media cannot compete with the influence of mainstream mass media for political messaging. Television and print media - and their mirror-sites online - will always be more powerful, because although their audience may struggle with its invisibility, they set the agenda for what counts as news. The news cycle is determined by the “professional content” that they produce, which is communicated as an event – the headlines, the breaking news.

The more familiar the genres, treatments and topics, the more the audience can relate to such content, especially in the tabloids. But the most important context for this shared experience people have with mass distributed news is the simultaneous reception of the news itself.

Not to be confused with “liveness”, this “current of simultaneous event reception” that characterises the morning prayer of the newspaper, or the hourly radio news, or the attempts by television networks right now to bring the evening news earlier (with full 4pm bulletins on Channel 7 and 9), is all about capitalising on the unique ability of such spectrum-scarce media to set agendas.

Here, the importance of media ownership really comes to the fore. This is especially so as it is the commercial media that have the most to gain, by erroneously arguing that their power is diminished in the face of “new media” and social media.

When successive communications ministers like former Howard government senator Helen Coonan and Labor’s Stephen Conroy (back in 2010), and shadow minister Malcolm Turnbull, herald online media as a source of diversity that opens the case for relaxing media ownership laws, they do so at great peril to Australia’s political culture.

The online world produces very little new content that can compete with the mass distributed content of the mainstream media. The proof of this is that most of the content of Twitter and even Facebook involves some form of mainstream media sharing, whether it be popular culture or the digitally shareable web-pages of news institutions. It is the mainstream media that enables meaningful opinion formation, that is then serialised on social media as much as it is in face-to-face communication.

In the rare event that online content does have an impact, it is usually because it is reported in the mainstream media, after which it receives a dramatic spike in attention and influence. Former Liberal senator Nick Minchin mischievously suggested on Friday that the Sky News make-up artist who posted up her assessment of Kevin Rudd on Facebook “shows the power of social media”. He argues that this would not happen in previous campaigns, “so social media is starting to really have an impact”.

The fallacy of Minchin’s claim is that the post only had 400 views before Sky asked their employee to remove it, only to have a lifted image of the post viewed by up to 1,170,000 readers on the front page of Sydney’s Daily Telegraph to pass judgment on the prime minister - that is when it “really started to have an impact”. As it happened, Rudd was actually touring the key electoral area of western Sydney on the day of the impact.

Social media can be influential when the following that a leader has on social media is itself reported in the mainstream media. Within the mediums themselves, there is the connection established for existing followers, but this can only be useful in a campaign if it is itself held up as being yet another poll of support. However, as it transpires, Rudd will need to do a lot more than amplify his support on Twitter if he is to win this election next weekend.

In the attention economy that is an election campaign, Rudd is up against a very clever opponent with agenda-setting powers a politician could only dream of - and I am not talking about Tony Abbott.