Catherine McKinnon graduated from Flinders University Drama Centre, South Australia, and was a founding member of the Red Shed Theatre Company, where she worked as writer and director.

After a period in South Australian theatre, she moved to Sydney to complete a Masters in Creative Writing at UTS, where she began her first novel, The Nearly Happy Family (2008). She followed it with Storyland (2017), written while undertaking her PhD.

Her work been nominated for an AWGIE Award, the Jill Blewett Playwright’s Award, and the Indie Awards. Storyland was shortlisted for the Miles Franklin Literary Award, the Barbara Jefferis Award and the Voss Literary Prize.

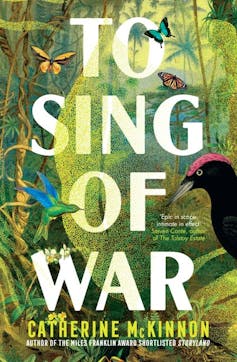

Review: To Sing of War – Catherine McKinnon (HarperCollins)

McKinnon’s latest book To Sing of War is a panoramic novel, which takes in multiple settings and characters in the mode of David Mitchell’s celebrated Cloud Atlas (2004). Like Storyland, it is a network of stories, with subtle overlaps.

Storyland was marketed as a book for readers of Kate Grenville, Tim Winton and Robbie Arnott, on the strength of its historical content and its compelling engagement with place and ecology. To Sing of War may prove to have even wider appeal due to its focus on World War II, including the Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb, led by the infamous Robert Oppenheimer.

Deeply influenced by Virgil’s epic poem the Aeneid, which begins with the phrase “Arma virumque cano” – “I sing of arms and the man” – McKinnon’s novel resists the glorification of war and the usual narrative of “us against them”, while respecting the unfortunate individuals who are either killed or suffer through the carnage. While it is concerned with the lives of soldiers, To Sing of War also consciously elevates the stories of women, children, queer folk and First Nations people caught in the crossfire.

The central story, set in Papua New Guinea, feels intimately imagined, probably because it is based, in part, on stories McKinnon inherited from her parents. She recognises that the locals were brutalised and manipulated by both Japanese and Australian soldiers, but there were also genuine bonds. When she visited Papua New Guinea to research her novel, villagers told her war stories that “folded into each other, forming a web of narratives that relate to the end of the war, to the dropping of bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki”.

Virgil Nicholson, the novel’s central character, is an Australian soldier fighting in the jungles of Papua New Guinea. He says “there’s never any rest in the jungle”. Yet there is a great deal of waiting. He survives ambushes and near misses, and witnesses the heartbreaking deaths of local children.

His close companion is Taiko, a Papuan boy named by the Japanese, who acts as a guide and saviour, especially when Virgil is delirious with malaria and must be transported back to Aitape for treatment. Taiko has a precocious talent for languages and reading, identifying himself with Ascanius, the son of Aeneas, who also had to “grow up quick”.

McKinnon evidently tries not to insert modern values into the conversations between characters. She allows them to speak their minds, whether they are exploding or perpetuating myths.

Virgil’s fellow soldier Bones is an Aboriginal man who quietly resents the ignorance of his non-Indigenous mates. In a heated conversation with fellow soldier Smithy, who thinks that blackfellas are all the same, he says: “Land isn’t for taking … It’s not a thing you take and pass around. Nothing to fight over.” Smithy doesn’t understand, so Bones tells him to forget it, because it “won’t make sense” with his radically different worldview.

Ness is a nurse stationed in Papua New Guinea. Originally from Aotearoa New Zealand, with a Moriori and Hungarian circus background, she practises knife-throwing for self-defence with Lotte Wyld, Virgil’s love interest. Ness tells a patient that “the Māori used to eat us for breakfast”, a reference to the killing and enslavement of Moriori by displaced Taranaki Māori in 1835, which generated a myth of widespread cannibalism that many Pākehā – a Maori term for white New Zealanders – have cited to justify colonisation.

The Māori-Moriori conflict on the Chatham islands also features in David Mitchell’s novel, suggesting an explicit link between the two texts.

Charlie the bastard

Bones and Virgil lug their platoon’s big gun, called “Charlie the bastard”, through the jungle – pointlessly as it turns out. McKinnon describes the smells, noises and ravishing beauty of the jungle as the soldiers doggedly haul this weapon across rough terrain, suggesting the haphazardness of this theatre of operations. Knowing the effort Bones expends to stay alive – and save others – it is chastening to think that he will not be rewarded for his service in the same way as Virgil upon their return.

The character of Tubby, who declares “Nothing can hurt me now” after taking communion, then suddenly gets shot by the Japanese, is based on a story told during a series of late night phone calls between McKinnon and her father. Shortly before a battle near the village of Dagmug, there had been a religious service, which McKinnon’s father had attended, despite having mixed feelings about religion. The platoon sergeant hugged him after the service, and was killed shortly afterwards.

There are skirmishes and sacrifices throughout To Sing of War, which emotionally wrench and visibly age the people who survive. When Lotte reunites with Virgil, after a series of letters, she notes that his eyes are darker and hollowed “as if plummeting from the surface of his face; his body taut, brown, but lean, oh so lean”.

War writing can sometimes be formulaic and clichéd, but McKinnon seeks a grittier view of war’s complexities. To Sing of War recognises the prevalence of sexual violence in wartime – something which is often overlooked in commemorations.

In the medical team in which Lotte works, there is an unknown rapist and a doctor who steals morphine from their dwindling supplies to self-medicate. Lotte nurses two Papuans, May and Lily, who were taken by the Japanese as comfort women, observing their incremental daily recovery despite the rejection of their community. Their return home must be carefully negotiated with a Swedish priest.

K.B. and Maude, a same-sex couple, are painfully separated by their respective war jobs. Lotte survives a rape attempt and teaches herself to use the knife she was attacked with. “Some people think women aren’t fit for war but they’re wrong,” Lotte reflects: “there are wars nobody knows you’re fighting. Women have been fighting those wars since ancient times.”

The air is foul

The Los Alamos sections of To Sing of War centre around the Trinity tests, which have come back into focus since the release of Christopher Nolan’s controversial film Oppenheimer.

The main figures in these sections are Oppenheimer’s troubled wife Kitty, whose passion for botany is suppressed by her entrapment in the domestic sphere, and Miriam “Mim” Carver, a scientist and amateur spy, who is torn between her friend Fred Johnson and a beautiful sex worker named Li.

Mim wrestles with a strong desire to inform the Russians about the “gadget” to keep the arms race balanced. While helping with the bomb’s development, she also chooses to reveal some of its secrets. In this high-stakes atmosphere, she doesn’t know who she can trust. The reader is shown the anarchic social life of Los Alamos, where a captive crowd awaits the finale of this risky top-secret project: “Trap this many people on one small square of land, Mim thinks, and there’s bound to be a compression of energy that needs to go somewhere.”

Following a dream in which a woman comments that “the air is foul”, Oppenheimer sees the death toll in a newspaper headline – “280,000 Casualties in Two Attacks” – and recognises that he will never recover from this fact: he will wear it forever.

To Sing of War boldly represents Japanese stories of loss, in a welcome counterbalance to Nolan’s film. The characters feel slightly distant, but are rendered with respect. McKinnon makes the notable choice to “disappear” the victims, rather than depict the horrific mangling of characters the reader has only just begun to know.

Fine threads link the stories. A three legged cat who comforts the distressed May is named Trinity, like the “gadget”. Antonio Bendetti, a Los Alamos scientist, is sent to fight in Papua New Guinea as punishment for his “happy socialist” sympathies. Kenzo, a prisoner of war, is the father of small children back in Japan. In one scene, he attempts to shoot Virgil, only for the bullet to be miraculously deflected by a stone bird Virgil was given by Lotte.

In Nagasaki, Kenzo’s wife Hiroko is preoccupied with keeping daily life going without him, caring for her two children and finding enough food to survive. She contemplates a haiku about an egret and thinks that the day is “like a new page, anything is possible, and always the sun will rise, and this the egret knows”. Hiroko is reflecting on the different natures of her children when her thought stops abruptly, indicated by a dash –

It is now, in the middle of this thought, that a light, brighter than the sun, shatters the sky, and in that moment, for as far as the eye can see, all life vanishes.

Kenzo’s grandmother is left to tell of their non-existence: “how will she tell him that those child smiles have gone?”

The omniscient narration allows deep immersion in the minds of multiple characters (though not all). At times, McKinnon has her characters engage in theatrical soliloquies, full of questioning. Lotte says to herself:

How can a person maintain any level of sanity surrounded by so much violence? What will it be like after the war? Will they ever be able to forget?

The futility and arbitrariness of war hits the characters who stay alive, especially the soldiers in Papua New Guinea, who are at war one day and emerging from the jungle alongside their former enemies the next. The Māori version of the song “Now is the hour” brings the exhausted troops together as the ship pulls out of the harbour heading for home. This is all that remains of their war effort. “What bravado there was has ebbed, and all that remains is song”.