The Sicilian mafia is arguably one of the most famous – or infamous – institutions in the Western world. After its first appearance in Sicily in the 1870s it soon infiltrated the economic and political spheres of Italy and the US and has, at times, been considered a serious threat to the rule of law in both countries.

But despite the fact that we’ve seen plenty of evidence of mafia activity, both in real life and on screen over the past 140 years, the reasons behind its emergence are still obscure.

While some analysis by academics has focused on weak institutions, predation and the poor state enforcement of property rights, others – particularly when it comes to the Sicilian mafia – have suggested that the legacy of feudalism was an important driver, along with the development of latifundism (a system according to which agriculture is dominated by large estates) and a loss of social capital and public trust in the government which was dominated by a foreign occupation.

These theories provide plausible explanations for the origin of the Sicilian mafia as a whole – but they fail to explain the considerable variation in the growth of the criminal organisation across different areas within the Sicilian region – especially when those areas experienced very similar socio-political conditions.

Working with Ola Olsson, from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, we recently published a study in the Journal of Economic History, in which we analysed the rise of the Sicilian mafia using a unique dataset drawn from the Damiani Inquiry in 1886. This was a parliamentary inquiry conducted between 1881 and 1886 that examined the conditions of the agricultural sector and of peasantry in every region of Italy. Our analysis emphasises the economic or market-related factors behind mafia organisation and focuses on local factors – rather than the overall political system under the oppressive Bourbon state in Sicily.

We found that the growth and consolidation of the Sicilian mafia is strongly associated with an external surge in the demand for lemons from 1800 on wards after the discovery of the effective use of citrus fruits to prevent scurvy by James Lind.

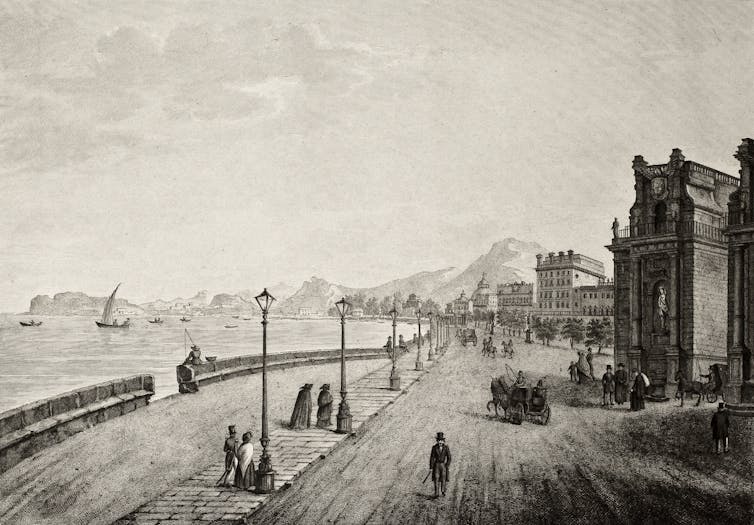

Sicily already enjoyed a dominant position in the international market for citrus fruits – and the increase in demand resulted in a very large inflow of revenues to areas focused on citrus production during the 1800s. Citrus trees can be cultivated only in areas that meet specific requirements (mild and constant temperature throughout the year and an abundance of water) – and this guaranteed substantial profits to the relatively few local producers in areas of Sicily that conformed to these requirements.

A combination of high profits, a weak rule of law, a low level of interpersonal trust and widespread poverty made lemon producers a suitable target for criminals. Neither the Bourbon regime (1816–1860), nor the newly-formed government after Italian independence in 1861, had the strength or the means to effectively enforce private property rights. So citrus farmers resorted to hiring private security providers to protect themselves from theft and also to arrange intermediaries between the retailers and exporters in the harbours.

A lot of this information can be found in the archives of the Damiani Inquiry. Questionnaires were sent to 179 pretori (lower court judges) asking, among other things: “What is the most common form of crime in the district? What are their causes?”

Oranges and lemons

When we looked at the archive, we found that mafia presence in the 1880s was strongly associated with citrus cultivation – no other crop or industry appeared to have the same robust impact on mafia activity. Our findings are supported by anecdotal evidence reported by the English author John Dickie in his 2004 book: Cosa Nostra: A History of the Sicilian Mafia and by the Italian historian Salvatore Lupo in his book Il Giardino degli Aranci (The Orange Garden).

Dickie named a Dr Galati as the first person persecuted by the mafia. Detailed records of his story can be found in Galati’s memoir: I casi di Malaspina e la mafia delle campagne di Palermo (Cases of Malaspina and the mafia in the campaigns of Palermo), and reported in the Bonfadini parliamentary inquiry, details of which are held in the national archives in Rome.

Galati’s attempts to sack his farm warden, a “man of honour” (mafioso) affiliated with Antonino Giammona, the boss of Uditore, a borough of Palermo, resulted in two replacement wardens being shot. The first was shot dead and the second, having recovered from three bullets in the back, cut a deal with Giammona.

Galati, who had reportedly spent more than 25 years building up his business in the area, fled to Naples from where he sent a detailed account of his troubles to the Minister of the Interior in Rome. Of 800 people living in Uditore, he wrote, there had been 23 killings in 1874 alone, including two women and two children. Another ten people had been wounded.

‘Men of honour’

Like Galati’s wounded warden, the safest option available to people under pressure from the mafia was to establish a relationship with their leaders – and get the most out of these connections. Niccolò Turrisi Colonna, for example, a landowner and politician whose 1864 study, Public Security in Sicily, warned that the Italian government’s brutal attempts to crush unlawfulness would only make matters worse by alienating the populace, is widely thought to have been a close associate of the aforementioned Giammona. He is also thought by some to have been the head of the mafia.

Another prominent Sicilian, Prince Pietro Mirto Seggio, hired as main warden for his farm a man named Giuseppe Fontana, the main suspect in the death of Emanuele Notarbartolo – an aristocrat, banker and a former mayor of Palermo. Notarbartolo’s assassination in 1893 is thought to be the first major mafia homicide in Sicily of a person not affiliated with a crime gang.

The Greco family – which was to become one of the biggest criminal enterprises in Italy and, in the 20th century, in the US, got its start thanks to the rent of a lemon grove extracted from the wealthy Tagliavia estate.

Like so many industries, legitimate or otherwise, the Sicilian mafia had humble beginnings, with its roots in the land. The boom in citrus fruits came at the right time for some of the more unscrupulous individuals in rural Sicily to take advantage of the lawless times and establish themselves as the real power in the land. And the rest, as they say, is history.