This April marks 200 years since Lord George Byron – “mad, bad and dangerous to know” as one of his lovers described him – died in Missolonghi, Greece at the age of 36. A rebellious, freedom-fighting Romantic poet, Byron’s reputation is the stuff of legend, his legacy assured and revered in the European literary canon.

While the star of Byron’s literary fame rose, however, many fell by the wayside, cruelly discarded by the poet. One of those women was Claire Clairmont. She was the mother of his daughter Allegra, whom he consigned to a convent in Italy for her schooling, where she died aged five. Clairmont is no more than a footnote in Byron’s history, but now a new novel seeks redress in telling the story from her perspective.

It was the summer of 1816, dubbed the “year without a summer” thanks to a volcanic eruption in Indonesia. Two of the most prominent literary figures of the late Romantic period, Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley (and his soon-to-be wife Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin), met in a villa on Lake Geneva.

But the catalyst for the meeting of these great minds is often overlooked. Retellings of the infamous summer acknowledge the presence of Claire Clairmont, Mary Godwin’s stepsister, now pregnant with Byron’s child after a brief affair. Some even note her role in engineering that meeting. Clairmont, desperate to pursue her relationship with Byron, persuaded her stepsister and lover Shelley – mired in a scandal of their own in England – to decamp to Lake Geneva for the summer.

Nevertheless, literary accounts of the meeting understandably tend to focus upon the infamous ghost story competition which challenged all present to come up with the best ghostly tale. That contest was the genesis of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. She later described it in her author’s introduction to the 1831 edition of her terrifying and groundbreaking novel.

Read more: Byron's letters reveal the real queer love and loss that inspired his poetry

A different perspective

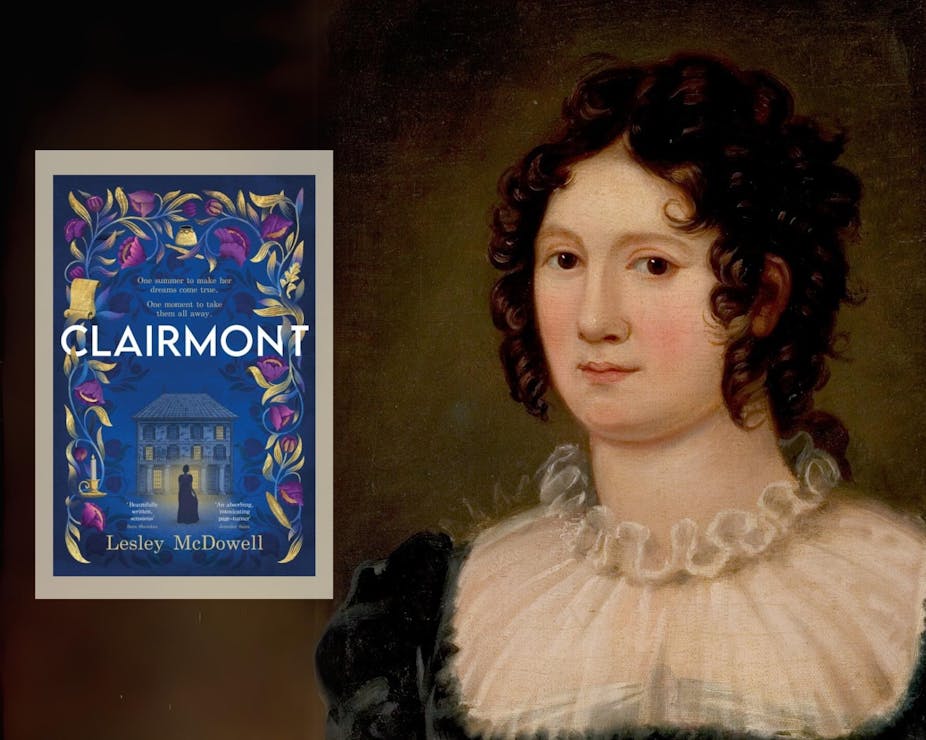

Lesley McDowell’s fine novel Clairmont (2024) offers a moving, erudite pivot to the story of the summer of 1816 in an effort to tell the story of the woman largely airbrushed from history. Viewed from the perspective of Claire Clairmont – but not narrated by her – the novel imagines and explores the feelings of the person who propelled Shelley and Mary Godwin to accompany her to Lake Geneva so that she could pursue her passion for Byron.

Once ensconced in the Maison Chapuis close to Byron’s accommodation for the summer, Villa Diodati, Clairmont’s affection for the wayward poet slowly erodes with the bitter realisation of her place in the social and intellectual hierarchy of the villa.

The beginning of chapter three explores Clairmont’s disillusionment. She leaves Byron’s bed one morning, intoxicated by the illusion that: “She’s a lover of a Great One. A mother-to-be of a Great One”. McDowell’s next paragraph abruptly halts this fantasy: Clairmont is seized by a “shiver of fear” that her baby “might despise its mother for not being a Great One herself. Lover of, yes. Mother of. Stepdaughter of. Stepsister of … ah, all those ofs.”

That fear is compounded by Byron’s arrogant and degrading treatment of her: he forces “Clairy Cocotte” to perform the role of Geraldine from Coleridge’s Christabel, demeaning her by ripping her clothes off in front of everyone assembled. Elsewhere, Byron calls her a handmaiden, making his feelings for her brutally clear by shaming her in front of the other guests.

The story is narrated across three different decades of Clairmont’s life, with chapters on the three decades interspersed throughout the novel. Cumulatively, they foreground the damaging legacy of that sexual relationship. “A handmaiden, Albe [Byron] had called her. He has no idea, she thinks, what being a handmaiden is like. But nobody has, because nobody wants a handmaiden’s story.”

Life after Byron

Clairmont is a tale of neglect and casual cruelty. Byron of course looms large, first in his attempts to end Clairmont’s pregnancy, and then in his insistence that their daughter, Allegra, live with him, only then to send her away to school. The novel also portrays the absence of empathy between Godwin and Clairmont throughout their lives, by drawing from correspondence and journal entries.

We see Godwin preoccupied by her own exhaustion and grief following the death of her first child in infancy, and envious and watchful of the relationship between Clairmont and Shelley. Byron and Shelley both died young, and in middle age, the mutual suspicion between the two surviving women persists. McDowell’s tale explores how Clairmont may have felt about Godwin’s lack of support and intervention in the decisions made about the fate of her child Allegra.

Clairmont imagines the resilience of Claire Clairmont. The second phase of the narrative shows her separated from the difficult relationships established at Lake Geneva, in part through loss and bereavement, but in part through deliberate choice.

As a governess in Russia in 1825, Clairmont’s young charge Dunya reminds her of her own dead child, Allegra. When Dunya also dies of fever, Clairmont is distraught, forced to leave her paid position and relocate. We next find her in Paris, in the arms of a much younger lover and awaiting with some trepidation the visit of her stepsister Godwin.

At one point, Clairmont bitterly reflects that Byron’s biographer: “Thomas Moore met with Mary, who told him as much as she wanted to about Albe, about Shelley. But who will meet with her, to hear what she wants to tell?”

As much as this is a tale about Clairmont’s romantic attachments, the novel offers readers an alternative perspective of the summer of 1816 through the eyes of the overlooked stepsister. Clairmont also urges us to reconsider the convenient sidelining of some lives as we give voice to others. It explores the painful sacrifice and erasure of female suffering at the altar of more “heroic” male narratives of love, idealism and creation.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.