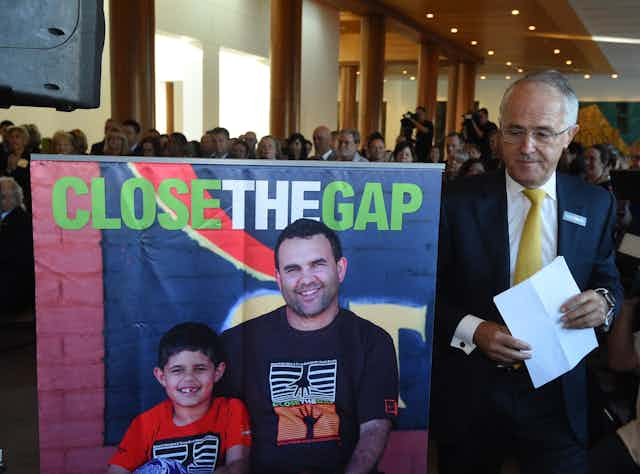

Malcolm Turnbull is the fourth prime minister to deliver the annual Closing the Gap report to parliament in its eight years of existence. Australian political leaders may find themselves easily dismissed, but the challenges of Indigenous inequality and disadvantage are much more difficult to displace.

The 2016 report represents Turnbull’s first substantial statement on Indigenous affairs since assuming office. He replaced the self-proclaimed “prime minister for Indigenous affairs”, Tony Abbott, who left little in the way of a policy legacy. In a climate of deepening divisions and frustration in Indigenous Australia, Turnbull’s statement to parliament will be carefully scrutinised.

Turnbull’s shifting focus

This year’s report acknowledges limited progress towards targets that the Council of Australian Governments originally agreed in 2008. The gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians has hardly changed. Indigenous employment rates have dropped.

In school education, NAPLAN results have shown inconsistent improvement in literacy and numeracy across all age groups. School attendance has not improved despite the federal government’s efforts.

The report presents little in the way of new data. It relies on the collection of statistical information from multiple agencies in different jurisdictions. Many of these have reporting cycles that do not fit the federal government’s reporting regime.

Abbott pronounced similar results a year ago as “profoundly disappointing”, but Turnbull’s emphasis is more positive. He drew attention to the discernible decline in mortality rates linked to circulatory diseases, substantial reductions in tobacco consumption, improvements in infant mortality rates, high immunisation rates, and strong results in Year 12 attainment and participation in post-secondary school education.

Abbott sought to reduce the complex Closing the Gap agenda to three key priorities, which were frequently captured in simple slogans – getting children to school, getting adults to work, and making communities safer. Each of these reflected a paternalistic judgement of apparent failures within Indigenous communities.

Turnbull has taken a different approach. He is focusing on opportunities and shared responsibilities, rather than failures.

Turnbull has explicitly expanded the policy agenda. He highlighted the role of economic development and the need to foster Indigenous entrepreneurialism, the importance of empowering women and girls, and shifting the policy focus to incorporate the almost 80% of Indigenous people who live in urban and regional areas – rather than concentrating on remote communities alone.

Using language more reminiscent of Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard in their reports, Turnbull evoked the need for evidence-based policy and a strong partnership with Indigenous peoples.

Are the reports helping?

Though commendable as a form of accountability – and as a means of keeping Indigenous disadvantage on the policy agenda – the annual Closing the Gap report has come to reflect a lot of what is wrong with Indigenous affairs.

The differences between each report reflect the prime minister’s own personality and priorities. But constant turnover in the political sphere undermines the sustained, long-term focus that genuine efforts to overcome Indigenous disadvantage will require.

The annual spotlight on the report also distracts from the shared responsibility for Indigenous affairs across all levels of government. Failures at state and territory level are too easily overlooked.

Attractive, glossy reports full of Indigenous art, photos and graphs too easily divert attention from the real implications of government funding cuts in Indigenous affairs. This is particularly the case with the introduction of the Indigenous Advancement Strategy and the shift to competitive tendering for services, to the detriment of many Indigenous-run organisations.

The reports list numerous policies and programs in place to tackle Indigenous disadvantage. But they fail to observe how the programs work, how long they have been in place and, in many cases, where the funding comes from and how it is allocated. Many of the programs are directed at the broader population, with Indigenous people receiving only a small proportion of the benefits.

The government’s reliance on measuring indicators and setting targets in Closing the Gap allows Indigenous affairs to be framed as an area of policy failure. But as Reconciliation Australia co-chair Tom Calma has observed:

The lack of progress should never be interpreted as a failure by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. It’s a failure of bureaucracy and a failure of the politicians to keep an even course and to keep the funding and the policy direction consistent.

Many Indigenous leaders, such as Noel Pearson and Patrick Dodson, have begun to distance themselves from Closing the Gap’s dominance in Indigenous affairs. Pressing issues that are frequently expressed by Indigenous people but not mentioned in the report include everyday experiences of racism at the personal and institutional level, the continuing importance of reconciliation, and the need for genuine empowerment of Indigenous communities.

Each year the Close the Gap Campaign Steering Committee presents its own parallel report on progress and priorities from the perspective of a wide range of peak bodies, including Indigenous peak bodies and non-Indigenous health professional bodies.

This year’s report emphasises the long timeframe needed for real change in Indigenous health outcomes. While expressing “cautious optimism” about progress to date, the report calls for sustained commitment to the goals. Importantly, the report argues that we should be paying attention to inputs – not just outputs – and demanding government accountability on both.

Turnbull’s first foray into Indigenous affairs will need to be followed up by substantial and meaningful commitments in the May budget.