As the world moves to combat climate change, coal is becoming increasingly vilified for its greenhouse gas emissions. But coal played a vital role in the Industrial Revolution, and continues to fuel some of the world’s largest economies. Our series examines coal’s past, present, and increasingly uncertain future, and today we turn to its role in the development of industrial relations.

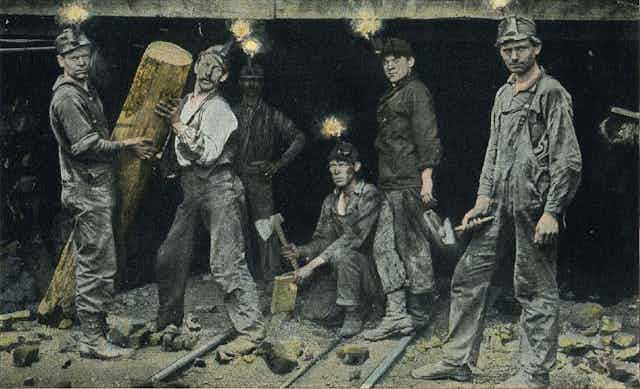

Coal mining, major industrial disputes, and the coal miner himself, are iconic representations of the industrial age. Demand for coal came from expanding urban centres as a result of the Industrial Revolution, and new coal-fired factories, mills and furnaces.

Miners were among the first workers to organise into trade unions from the middle of the 1700s, battling a lack of legal recognition and resistance from the mine owners.

By the 19th century, there were numerous attempts to combine and organise what were often local trade unions. By the beginning of the 20th century, lasting national bodies of miners had been formed in the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States.

Origins of mining communities

Small pit-top communities emerging in the 1800s created bonds of association that flowed into newly established trade unions. Mines tended to concentrate in distinct regions following coal seams.

Miners were fired by a sense of solidarity but also by dangerous working conditions, which produced high death and injury rates. Proper records were not kept in the early period, but in the United Kingdom, for example, at least 90,000 miners died between 1850 and 1914.

Disasters were common in the industry. Their collective impact and lasting grief created a long tradition of anger over working conditions. The prevalence of occupational diseases – especially respiratory ailments – further encouraged union formation, and was a rallying call for organisation and political change.

Starting in the late 19th century, mechanisation not only reduced the total number of miners needed to raise a tonne of coal, it also introduced new hazards into the workplace. Machines with high-speed moving parts could catch clothing and limbs, causing serious injury or death.

In Australia and the UK, regulation usually followed major disasters. The US mining industry was more lightly regulated and only serious disasters prompted concerted federal government action; a situation that was unfortunately mirrored in other parts of the world. From 1900 to 1947, more than 90,000 US miners died at work.

Industrial conflict

By the late 19th century, the industry was characterised by uncertain profit margins, seasonal shifts in demand, uncertain supply lines, and owners who increasingly resented the rise of unions.

Mine owners were pressing for lower wages or faster work rates, and industrial conflict was common. And as older, more paternalistic forms of management of the early 1800s began to recede, the industry was characterised by major industrial battles.

On the eve of the Great Strikes of the early 1890s in Australia, for instance, there was evidence that mine owners, in league with other employer groups, had decided to make a stand against the rising tide of union power.

Miners had joined other workers in asserting the right to form their own associations. They encouraged unions in new secondary industries and in other mines. In places such as the Hunter Valley in New South Wales, coal miners helped workers organise in the new base metal mines of the 1880s, and later in the Newcastle iron and steel industry from 1915.

In the US, there were violent and deadly clashes between miners and state and federal militia including the infamous 1914 Ludlow massacre in Colorado, where more than 60 strikers were killed.

In Australia, a seven-week miners strike in 1949 over wages and conditions but made worse by Cold War fears, saw federal government intervention and soldiers working in the mines.

Mining communities

Miners were also important in the development of the labour parties in Australia and the United Kingdom.

In the 1930s and 1940s, coal-mining communities in Australia, Wales, and England included members of the Communist Party. But the Labour parties were by far the dominant group, and mining communities would supply staunch Labour party politicians for many decades.

There was strict gender division of labour in coal-mining communities with men as breadwinners and women as wives and helpers. If women organised, it was in an “auxiliary” role.

Religion was often an important part of mining communities and this usually took the form of Protestantism that preached an acceptance of one’s fate; hyper religiosity in the face of the deadening weight of wage labour and the daily possibility of injury or death prevailed.

By the 1950s and 1960s, unionised coal miners had won better pay and conditions. In conditions of low unemployment and with the prestige garnered by their national organisations, coal miners had significant industrial power.

The withdrawal of their labour could bring an economy to a standstill as coal was required for factory machinery and transport. But towards the end of this long boom period, coal began to lose out to oil and gas.

The radical miner?

There is a common misconception that most coal miners were militant socialists. But miners and their communities could be socially conservative moderates who worked within the capitalist system.

Pit-top communities were homogeneous, and solidarity was often enforced through intimidation and exclusion, as well as moral consensus.

Working in a coal mine did not inevitably produce a radical political consciousness. Where strong union organisation was present, it was the result of hard work and efforts to organise members focused on protection rather than revolution.

The UK miners’ strike protesting mine closures in 1984-85 was an occasion when, in the face of strong external threats, communities did come together powerfully.

With long memories of successful miners’ strikes in the early 1970s, Margaret Thatcher’s government embarked on a concerted attack on coal communities. This included plans to call in the military if needed, and reduce the power of the coal miners by encouraging nuclear energy.

But even in this case, the ultimately unsuccessful strike also produced internal dissent, a rival workers’ organisation, and broke the exclusive coverage of the union in mining jobs.

Recession and globalisation

Coal mining continued to offer good jobs for working class communities but, increasingly, the jobs were being shifted to the developing world. And miners were losing their industrial and political muscle.

By 2007, there were 41,000 coal miners in the United States but only 22% were unionised. Recent high-profile bankruptcies of major US firms have again highlighted this development.

The centre of the global coal industry is now China. It accounts for 40% of global production; up to 80% of global coal mining fatalities; and no independent union representation.

Away from the spotlight of large mines, informal or artisanal coal mines are important in the developing world. While these small mines are important sources of income for poor communities (especially for women and children), conditions are squalid, safety unregulated and figures on the loss of life or serious fatalities largely unknown.

The reality of climate change has transformed the standing of coal mining. Those on the left were once unfailingly proud of their militant tradition. But as coal became associated with human-induced climate change this became less tenable.

The industry that spawned major unions, heroic though often unsuccessful industrial action, and transformed the political makeup of the UK and Australia, is now increasingly struggling. While the UK has only a handful of operating coal mines, the Australian situation is complicated by the renewed expansion of mining, including coal mining, from 2001.

This is the third article in our series on the past, present and future of coal. Look out for others in the coming days.