The current understanding of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is like an academic echo of the famous song Universal Soldier. The song imagines the warrior as timeless, unchanging, universal. According to leading historians and theorists, all soldiers experience war in a similar way. They are universal. So the logical conclusion is surely that conditions such as PTSD, which affect modern troops, must also have afflicted their ancient counterparts. But this couldn’t be further from the truth.

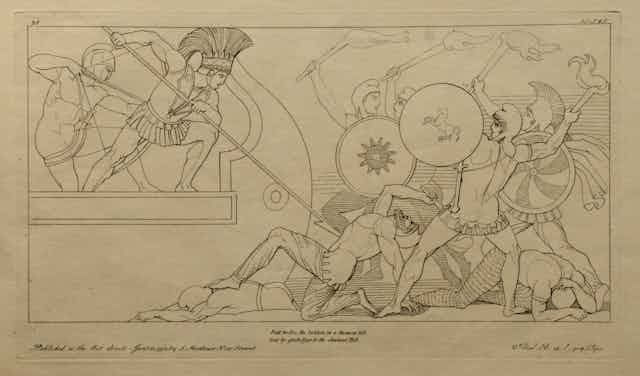

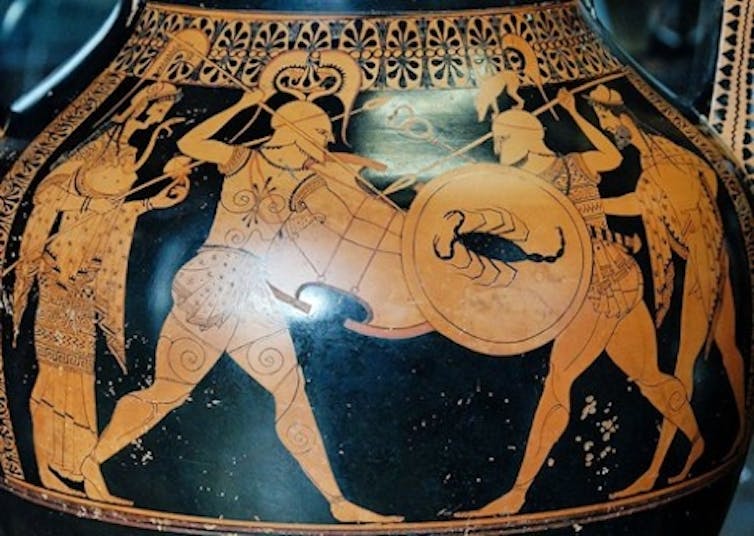

Those men, of course, faced a grim and bloody ordeal on the ancient battlefield. Take, for instance, the citizen soldier hoplites of Classical Greece, those warriors made famous by glorious victory at Marathon in 490 BC, and even more glorious defeat at Thermopylae ten years later. They didn’t have the luxury of engaging their enemy at a distance like modern troops armed with sophisticated firearms - hoplites were armed with edged weapons, so when they killed their enemies, they did so face to face, stabbing them to death with spears, and when those spears splintered in the fury of close combat, they hacked their opponents down with short swords.

This experience, to us, seems utterly horrifying. Unsurprisingly, scholars believe that many of those who survived it would have suffered from PTSD or similar stress-related injuries. Such was the intensity of combat on the ancient battlefield that not even Homeric heroes, like Achilles and Odysseus, emerged unscathed. According to Jonathan Shay, both the Iliad and the Odyssey are tales of men who are psychologically damaged by their experiences of war.

Such trauma is easy to imagine, and that’s why this universalising view is fast becoming unchallenged dogma. It has an intrinsic appeal. It flatters our faith in humanity, it makes the ancient world seem more relevant, and it refutes the unjust but lingering accusation that the soldiers who fought in Vietnam, whose experiences led to the formulation of PTSD, were psychologically weak.

So it’s no wonder that this view has persuaded so many. Even leading theorists and clinicians who are actively involved in the treatment of psychologically injured troops, such as those who set up the excellent Royal Marines’ Trauma Risk Management Programme, accept it without question. And that’s a big problem, because the universal view is, quite simply, wrong.

Soldiers are not universal. PTSD results from the interaction of an individual with their environment, and neither of these are historically constant. The beliefs adopted by warriors change, as does the socio-military environment in which they fight.

And the nature of these changes are extremely important. The 20th-century soldier, for example in Vietnam, was susceptible to PTSD not because he was psychologically weak, but because he was exposed to a range of conditions closely associated with PTSD. He was often exhausted and sleep-deprived when he met his enemy. He fought socially and physically isolated from his comrades. He faced threats he could not counter and, perhaps most crucially, when he killed he transgressed the peaceful norms he’d been raised to cherish.

The 20th-century American soldier, then, faced a near perfect storm of psychological adversity. By contrast, the situation faced by the Greek hoplite, was, in psychological terms, much more benign. The hoplite (whose campaigning season was brief and who did not generally fight at night) was not routinely exhausted or sleep-deprived when he met his enemy. He was socially integrated with and fought in close physical proximity to his comrades, he was able to counter the threats he faced – and when he killed, he acted in accordance with his religious values. In killing he complied with a core principal of traditional morality, which demanded he help his friends and harm his enemies.

In short, the conditions required for PTSD are present in the modern case study but absent in the ancient. And that means PTSD is not universal, it is historically and culturally specific.

Accepting that the soldier is not universal, always a product of both his time and his culture, is extremely important. It strips away the illusion that other peoples from different historical periods were just like us, and once freed from our intellectual neo-colonialism, we can more fully appreciate the diversity of human experience and the richness of our past.

But more immediately, if we accepted this it would mean that we would no longer treat our psychologically injured soldiers on the basis of a false premise. We are not all the same and if a better appreciation of the importance of socio-cultural factors enhances our understanding of PTSD, then maybe we can find more effective ways of treating that condition.