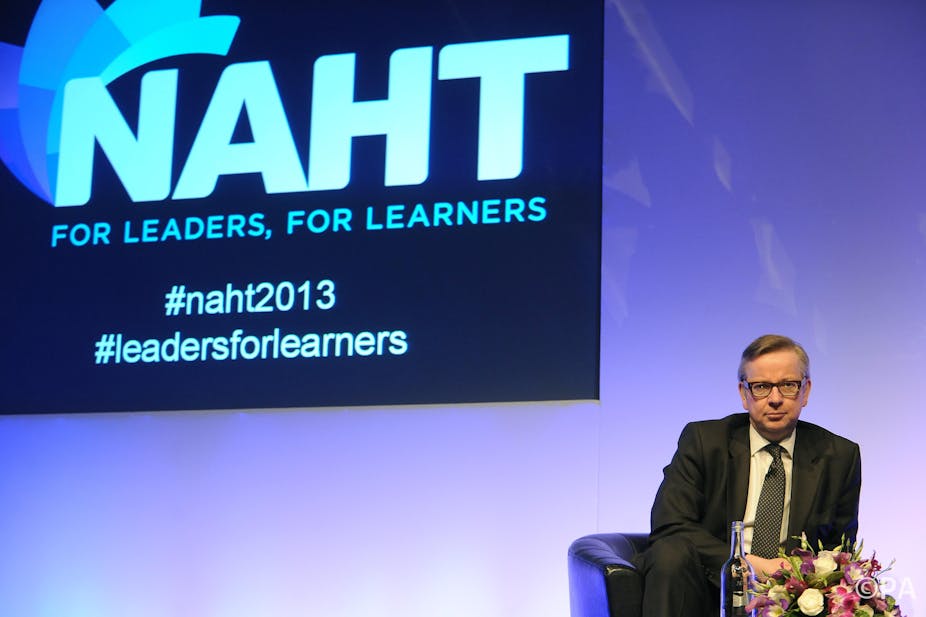

The complex web of teacher trade unionism in the UK is about to become even more convoluted and competitive. One of the headteacher unions, the National Association of Head Teachers (NAHT), has announced its plans to launch an “affiliate association” called NAHT Edge. It is seeking to recruit “middle leaders”, teachers with additional responsibilities in schools and who are “aspiring” or future leaders.

But this further split of the teacher union movement is in danger of further dividing a profession that desperately needs unity in the face of attacks on many fronts.

Multiple teacher unions in the UK already recruit different types of educational worker and organise in different educational sectors. This “multi-unionism” tends to be a global feature of teacher unionism, although it is hard to find any other national or local context where the picture is as complex as it is in Britain.

Despite all the moves towards union mergers at a general level, such as the emergence of super unions exemplified by Unison and Unite, teachers have defied these trends. The situation is most complex in England and Wales rather than Scotland, where a single union, the Educational Institute of Scotland, represents a very large majority of the school sector workforce.

In England, there are six unions seeking to recruit teachers in schools alone, leaving aside the further and higher education sectors. Two of these unions, NAHT and the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL) seek to recruit from school leaders, including headteachers and school business managers. The other four unions recruit primarily from amongst classroom teachers, although most also recruit school leaders.

Some unions, such as the National Union of Teachers (NUT) and National Association of Schoolmasters Union of Women Teachers (NASUWT), recruit very largely amongst teaching staff (an increasingly difficult group to define as the government de-regulates the need for professional qualifications), while others, such as the Association of Teachers and Lecturers, also seek to organise support staff.

This competitive unionism in which different unions compete for largely the same potential members, is one of the defining features of teacher unionism in England. This contrasts with what is sometimes called adjacent unionism, in countries such as New Zealand, where different unions recruit different sections of the same workforce.

Union turf wars?

In this context, the creation of NAHT is a significant development. It represents the first time that one of the headteacher unions has sought to expand its membership base by extending membership to “classroom teachers”. As such it represents a direct attempt to compete for members with the main classroom teacher unions.

Some have tried to suggest that the new union deliberately seeks to appeal to those opposed to industrial action although NAHT General Secretary Russell Hobby has denied this.

Ironically, it follows shortly after a recent Professional Unity conference in which several unions, including NAHT, pledged to work more closely together. Two of the main classroom unions (NUT and ATL) appear to be having serious discussions about the possibility of forming a single, united organisation, although the NASUWT continues to set itself against this.

Some, such as Chris Keates, general secretary of NASUWT, have defended the existence of multiple unions. In 2011, she argued in the Times Education Supplement, that: “Where there are big, dominant unions, and where there are no other players in the field, what you often find is they are not necessarily focused on their members’ interests.” This argument claims competition ensures unions “keep on their toes” – providing a good service and offering value for money. NAHT’s Edge initiative draws on a similar logic.

A new business unionism?

What is not clear is whether this language of business – “consumer choice”, “competition”, “market segmentation” – is an appropriate basis for effective trade unionism. Trade unions were formed to challenge the logic of the market, whereby competition between isolated labourers was experienced by workers as a constant downward pressure on pay and conditions. That is how workers learned the need to unite and organise.

Teacher union disunity cannot explain all the problems that teachers have faced in England in recent years. But there can be little doubt that one of the reasons behind the quick neoliberal restructuring of state education in England has been due, in part at least, to the inability of teachers to mobilise a collective and united response.

This drive towards privatisation, the introduction of performance-related pay and the dismantling of national pay has been experienced in England more sharply than almost anywhere else in the world (the USA and Chile excepted).

Given the above, it is hard to see how the emergence of increased competition, division and fragmentation within the teacher trade union movement is going to help teachers (and school leaders) reclaim the initiative in relation to the education policy agenda.

A divided profession has already resulted in schools looking increasingly like businesses, illustrated by Ailsa Gough, an academy principal in Nottingham who recently stated: “We operate differently from a school. Our approach is based on a business rather than a school model.”

If teacher unions are to challenge the further commercialisation of public education they need to stop behaving like businesses themselves. Unions work best when they challenge the logic of markets, rather than replicate them.