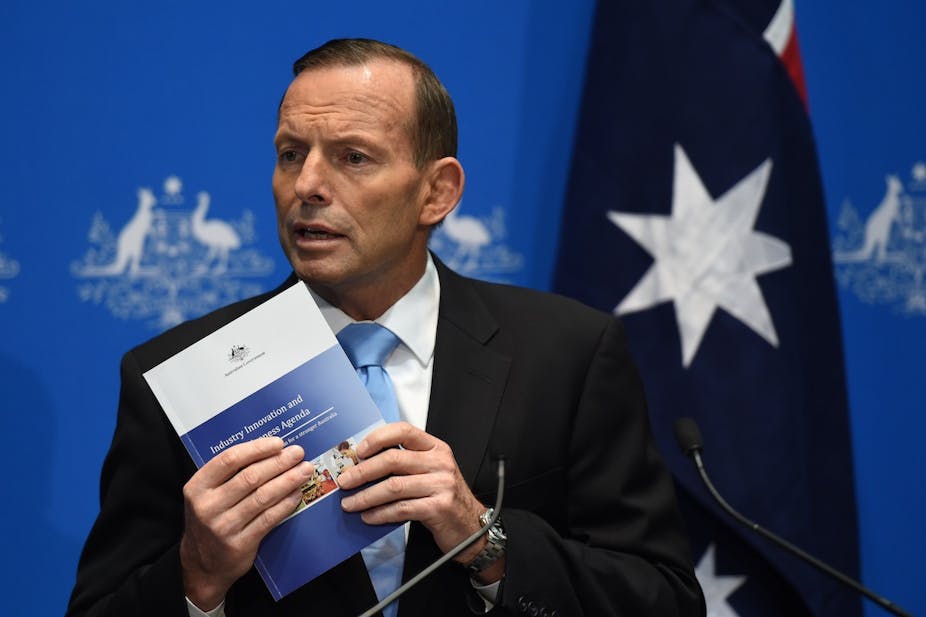

The federal government has released its National Industry Investment and Competitiveness Agenda, committing around A$400 million towards “industry growth centres”, new tax incentives for employee share schemes, and a push for science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) education.

The government has chosen to focus on five sectors for its growth centres: oil and gas, mining technology, medical technology and pharmaceuticals, food and agribusiness and advanced manufacturing, where it says Australia has a “natural advantage” it can build on.

Each of the five industry-led centres will receive funding of up to A$3.5 million per year, and be required to establish a plan to become self-sustaining after four years. Grants of up to A$1 million will also be on offer for the commercialisation of ideas.

The government said it would also reform the tax treatment of employee share schemes to support start-up companies, beginning with reversing the changes made in 2009 to the taxing point for options. There will also be new concessional tax treatment of options or shares issued by unlisted start-ups with turnover of $50 million or less.

The 457 visa program will also be reformed, with the process of sponsorship, nomination and visa applications for “low risk” applicants streamlined, English language requirements made more flexible, and the sponsorship approval period increased from 12 to 18 months for start-up businesses.

As part of its ongoing deregulatory agenda, the government will adopt a new principle that if a system, service or product has been approved under a trusted international standard or risk assessment, then Australian regulators would not impose any additional requirements for approval.

The government will also introduce a new “Premium Investor Visa” offering a faster 12 month pathway to permanent residency, for those meeting a A$15 million investment threshold.

A symbolic A$12 million of funding will be provided for programs designed to improve the focus on STEM subjects in primary and secondary schools.

The government will also establish a “Commonwealth Science Council”, chaired by the prime minister, to advise the government on areas of national strength, current and future capability and on ways to improve connections between government, research organisations, universities and business.

The government will host a series of roundtable sessions in coming months to consult with business and the research sector on the policy.

A panel of experts responds below.

Joanna Howe, Lecturer in Law at University of Adelaide

Today’s announcement by the government of a number of changes to the subclass 457 visa program represents a missed opportunity to properly reform Australia’s approach to temporary skilled migration. There is genuine public concern that temporary migrant workers are being used in areas where no skill shortage exists, thereby displacing job opportunities for Australian workers. This point was recognised by the recent independent review into the subclass 457 visa program, with the final report identifying that two core questions of the program, namely “proving that the position cannot be filled by a local worker and determining the skilled occupations that are used for the programme” are “not well served by the current policy approaches and can be improved by adopting a more robust evidence- based approach”. Yet, the government has sidestepped both these issues in the reform package announced today and ignored the report’s recommendations for a ministerial advisory council to provide expert advice on the composition of the occupational shortage list used by employers to access temporary migrant labour.

The decision to streamline the application process for low risk applicants is a positive one, as is the proposal to increase the sponsorship approval period for start up companies. Yet, ironically, a reform that would offer far more efficiency gains and was recommended by the independent review, but has not been adopted by the government, is the abolition of employer-conducted labour market testing. This would greatly aid employers and the Department of Immigration but the government seems unwilling to tackle this reform because it would be difficult to get through the Senate. Yet, the weight of scholarly evidence and indeed, the OECD’s recommendations on this point, suggest that independent labour market testing is a far better alternative.

A concerning development is the government’s proposal to weaken the English language requirement. This is currently a minimum of five across the four competencies (reading, writing, speaking and listening). The main function of the English language proficiency requirement is to ensure a 457 visa holder will not be exploited. If temporary migrant workers have lesser language skills, this could leave them vulnerable to potential health and safety risks in the workplace.

Another concerning reform is the proposal to freeze the Temporary Skill Migration Income Threshold (TSMIT) at its current level and to review the role of the TSMIT in two year’s time. Like a strong English language requirement, the TSMIT has a key role in protecting the integrity of the program overall. It was introduced following the Deegan Review into the 457 visa to act as a salary floor ensuring a visa holder’s wage was sufficient to maintain a reasonable standard of living given the lack of access to welfare and tax benefits available to local workers.

*Ian Maxwell, Adjunct Professor at RMIT *

The concept of promoting STEM skills in schools addresses the continuing slide in the quality of high school graduates in these areas – as I have heard anecdotally from friends that teach these subjects at university. In fact, in Australia we have far too many university graduates in science and engineering and the result is that (a) there is downwards pressure on graduate salaries (further reducing the quality of people entering these degrees) and (b) there is an increase in the number of people that have science and engineering degrees that go onto to work in unrelated areas. My personal preference would be to promote special purpose high schools with a focus on science and engineering where we can put our limited resources into a fewer number of highly skilled and motivated students.

The idea that we in Australia accept international standards and risk assessments for certain product approvals is a great one. For too long, especially in the more mature industries, we have seen oligarchies in Australia exploit standards organisations in order to keep out foreign competition. This has had two unwanted consequences; firstly, it has put upward pressure on relative prices for Australia customers (due to less competition), and, secondly, it has acted as a disincentive for Australian producers to expand their focus overseas. The question is whether this new principal only for newly emerging standards, or if this brush will also be run over existing standards.

The government says it will provide A$188.5 million to fund “Industry Growth Centres” in five key sectors. There are very few details so it is hard to comment on this one other than to say that this represents a (mean) expenditure of $37 million for each of the so-called growth sectors and it would be pretty silly to expect any significant national economic outcomes from such low levels of expenditure.

*Jim Minifie, Productivity Growth Program Director at Grattan Institute *

For a refreshing change, the Industry and Competitiveness Agenda is a readable document that clearly sets out what the government has done and aims to do in pursuit of four goals (business environment, labour force, infrastructure, industry policy).

While the “have done” list includes some questionable calls like ending carbon pricing and the “will do” list includes some questionable commitments like the paid parental leave scheme, the concrete new initiatives announced in the Agenda look broadly sensible and do not cost much. Three of the initiatives could turn out to be big contributors to startups, gains from trade, and skilled migration. The program offers substantial spending on apprenticeships, and several smaller funded programs.

Reforms to the Employee Share Scheme (ESS) taxation arrangements are overdue. Paying employees partly in shares or share options can be a great way for cash-strapped start-ups to reward employees while burning through a minimum of cash, but since 2009, Australian start-up employees could have to pay tax at issuance. Start-up employees have been in the absurd position of having to pay tax well before their shares can be sold for cash. While some start-ups have found ways around the restrictions, many say the rules sorely limited the value of share schemes in Australia. Shifting the point of taxation back will make make it much easier for start-ups to make attractive offers to their employees.

A tougher test on the creation of Australian standards is also welcome and overdue. Before a new Australia-specific standard can be set, regulators will need to show that there is a good reason to introduce one. Government will also apply the new test to existing Australian standards, not only new ones. Standards can be a two-edged sword: they can reduce the costs to buyers of assessing quality; but they can also be used to benefit firms whose products meet the standards by restricting competition. The reforms should also help Australian exporters achieve production scale by using a single certification for domestic and international markets.

Reforms for skilled migration are sensible as well, if relatively minor. Research overseas has shown that skilled migrants do not take jobs away from locals, but instead can boost their incomes. Skilled migrants can make locals more productive, start businesses that employ locals, or help local firms plug into international networks. Anecdotally, technology firms in some cases have had difficulty attracting top international talent. It’s less clear whether clearing the way for so-called significant and premium investors will add much value; in principle, reducing the barriers to equity capital inflow could be useful as investors can start new businesses where they live. Australia’s dividend imputation rules do probably bias foreign investment towards debt rather than equity, so there may be a broader case for to attract foreign equity including through investor visas.

STEM education in Australian schools has lagged, with enrolments falling in the 2000s, and many schools saying they are short of teachers with strong mathematics and science qualifications. While questions can be raised about whether the demand is there for tertiary STEM graduates, it’s much easier to make the case for stronger secondary STEM education, which creates options for students and builds foundation skills.

Finally, five Industry Growth Centres will get seed grants and will be able to apply for further funding. The model brings to mind the Innovation Precincts of the previous government. The focus areas (food/agribusiness; mining technology and services; oil, gas and energy; medical technology; and advanced manufacturing) are not a million miles from those suggested by the Business Council of Australia’s work with McKinsey. The logic for a subsidy is that firms can be reluctant to innovate where they expect others will capture benefits.

Australian universities do not score well on “translation” to industry. The logic for the sectors chosen seems to be that the payoff may be biggest in large or rapidly developing sectors. While a case can be made for action, the evidence base for the value of such programs is relatively weak. As long as the programs are built from the beginning with evaluation built in (and funded), they have some chance of paying off and will at least teach us about what doesn’t work.

John Rice, Associate Professor in Strategic Management at Griffith University

The promise of $185 million to establish five new “Industry Growth Centres” (in the areas of food and agribusiness, mining equipment, technology and services, oil, gas and energy resources, medical technologies and pharmaceuticals; and advanced manufacturing sectors) can be seen as a re-packaging of funds that have previously supported the eleven “Industry Skills Councils”, albeit with a focus on innovation rather than skills and training quality. Handily, the acronym doesn’t change!

Notable sectoral absences among the newly established centres are the service industries in Australia – clearly not a good omen for those industries that have not been favoured by inclusion in the narrow mandates of the new centres. In terms of governance arrangements, the new centres are clearly industry driven, while the sidelined skills councils were, to a greater or less degree, tripartite in nature with a clear role for unions.

What is lacking is a clear policy framework for industry development that encompasses skills, investment and innovation. The previous Labor government created a bricolage of bodies in the skills and innovation area with overlapping responsibilities (that even insiders struggled to understand), extraordinary bureaucratic waste and scams that siphoned State VET funding.The current government has rationalised many of these bodies, but today’s announcements in VET and innovation replace the bricolage with an equally unacceptable patchwork.

The Minister also announced half a million dollars in funding to assess the development of P-TECH-like programs in Australia. These have been developed in the US and link private employers, educational providers and (generally) low socio-economic students. In Australia, private firms have accessed public funds previously to train their employees – and generally this has not gone well.

Anecdotes of burger flippers being surreptitiously enrolled in VET programs as a means of siphoning public funds haunted the sector a few years ago. It is important that P-TECH does not emerge as a similar scam.

Suspending my natural cynicism, however, linking employers and trainees is a good thing if it is accompanied by a sense of mutual obligation. It would be tragedy to invest heavily in narrow skills sets that become worthless if a multinational employer opts to leave Australia. As such, skills should be relevant and generic, and not focused too narrowly on the processes and systems used in specific firms.

*Rachel Wilson, Senior Lecturer at University of Sydney *

Research has shown that educational attainment (reading, science and numeracy on PISA) and IMF measures of competitiveness are highly correlated. In Australia, however, we have declining participation and levels of attainment in STEM education that threaten future economic competitiveness. Contrast this with the massive investment, strong participation and high levels attainment in STEM among our competing and neighbourhood economies, like China, or with others, and the picture looks grim – we risk being left behind. Therefore this policy attention is very welcome and needed.

My concern is that it is still a very modest investment and is not targeted for the best bang for our buck. Provision of teaching resources is important but not as important as teacher professional development programs – particularly those focusing on teacher pedagogical content knowledge in STEM. There is evidence that those entering the teaching profession also have declining participation and attainment in science, math and technology; and current efforts to lift teacher quality are not focused on these areas. There is no requirement for teachers to have completed intermediate level maths or any science for HSC – and many do not.

The focus on a pilot program and Summer schools for students too, while admirable, will not have wide reach. Indeed there have been many such programs promoting students interest in STEM and innovation in schools over the past two decades, yet concurrently many students have dropped study in these fields and our attainment levels among 15-year olds are declining. More attention needs to be paid to teacher knowledge and pedagogy in STEM, in early childhood through to university, and on structural policy issues relating to how STEM is valued, or not, within educational curricula. In NSW the requirement for either maths or science at HSC was dropped in 2001 and since then numbers have been in decline. We cannot hope that programs to lift interest among students, so proliferate among education systems worldwide, will alone make a difference to our current position. Braver reform is needed.