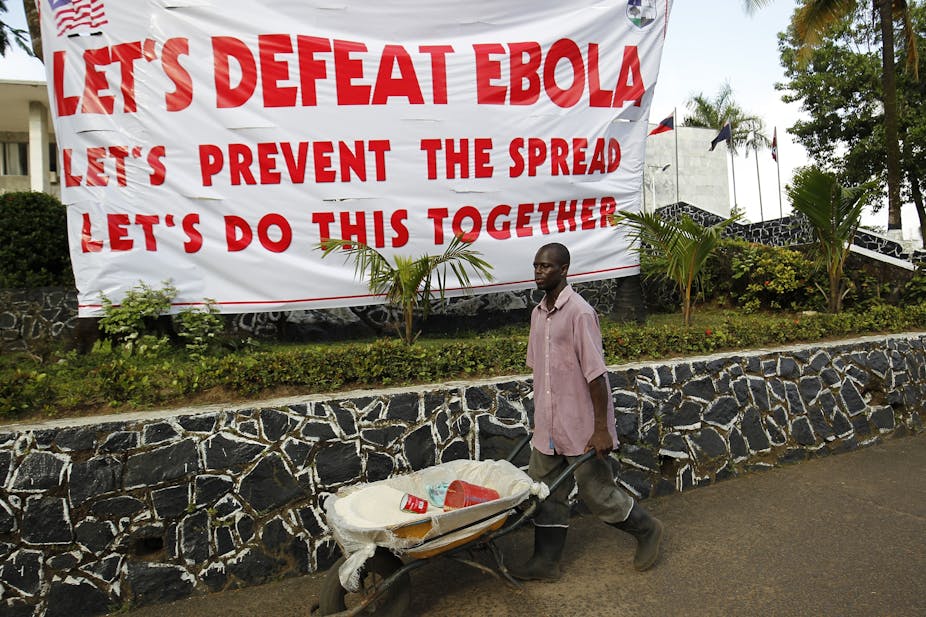

There seems to be no end in sight to the Ebola outbreak that has swept through the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) since last August. By 19 June, nearly 1500 people had died. Uganda is on high alert after three positive cases, two of them fatal, were recorded in the country. And there’s been an Ebola scare – thankfully, the suspected case proved negative – in Kenya.

What will it take to end this, the second worst Ebola outbreak in history? As social scientists who have been conducting research in Sierra Leone since 2015 to understand communities’ experiences of the 2014 - 2016 West African Ebola outbreak and the response to the epidemic, we believe that at least part of the answer lies in understanding the DRC’s unique context.

The West African Ebola epidemic had its epicentre in Sierre Leone. It claimed 3956 lives between 2014 and 2016, and brought to the fore the fundamentally social nature of diseases like Ebola. Health officials encountered community resistance – even violent rejection of intervention in some cases. They had to deal with people’s fears, alongside rumours about the disease.

This revealed the need to understand community dynamics, local beliefs, legacies of inequality and marginalisation. Health workers and authorities also need to understand why people may not trust them during an epidemic response. This knowledge can inform medical interventions capable of establishing positive and productive relations with local communities.

By thoroughly investigating community attitudes, beliefs and fears, and tailoring solutions that take these into account, the DRC will be an important step closer to tackling the latest outbreak. This will contribute to improving the uptake of vaccines for prevention and early treatment.

Power dynamics

In Sierra Leone, histories of foreign conquest, economic collapse and a civil war contributed to low trust in national and international response institutions. In marginalised informal settlements and border communities, the sudden arrival of the state in the form of health officials and men and women in military uniform created concerns due to these histories.

In DRC this is even more sensitive. As UN officials have warned, the long-term conflict in North Kivu (which is the epicentre of the outbreak) is unpredictable. It is hampering response efforts. In such a context, sensitive negotiations and trust-building are even more important.

Through our research in Sierra Leone, it has become clear that understanding public authority is key to an effective response. Specifically, efforts to gain trust means acknowledging power differentials within affected communities.

In Sierra Leone, it was apparent that trust in “formal” leaders is not universal and cannot be assumed. It is essential to map power within communities. This involves understanding who has influence in what context. This can then be harnessed to lead prevention efforts.

The response itself also reshapes trust and power within affected communities. For example, in Sierra Leone stories emerged during the outbreak that certain leaders and communities were “eating” – benefiting from – Ebola money, while others were being excluded. In exploring these stories about “Ebola business”, it was important to take into account how emergency responses affected local economies.

Similar dynamics can be seen playing out in North Kivu. There too are concerns about who benefits and who loses from “Ebola business”. Rumours are also rife that Ebola is a hoax for exploiting vulnerable communities.

It is essential to avoid framing these concerns as “ignorance” or misunderstanding. Instead, they reflect meaningful anxieties and feelings of injustice that must be taken seriously. This is why it’s important to create space for locally-led community engagement, and to listen and engage with anxieties, anger and expectations. As a group of experts in community engagement for health research recently argued, it will be difficult to increase trust in response activities without such engagement.

Trust is particularly important when it comes to health services.

Building trust

In the early stages of the epidemic in West Africa, there was extensive documentation of distrust of ambulances, treatment centres, safe burials and quarantine efforts. This sprang from a lack of community involvement in the set-up and delivery of such response efforts.

Better engagement with communities, as well as more transparency about the services improved this trust.

However, such distrust was also rooted in pre-epidemic experiences with health care services. This too is playing out again in the DRC. Continuing to strengthen non-epidemic related health services during an outbreak should therefore not be sidelined. It must remain a priority.

These suggestions require everyone involved in fighting the epidemic to understand the political, economic and historical factors at highly localised levels that affect trust. This will require strengthening rapid and in-depth social science research, and integrating the learnings into response activities, including community engagement.

The West African outbreak captured the international imagination. But in the DRC, as Gayle Smith from the ONE Campaign has pointed out,

we’re missing the same urgency.

It’s critical to find ways to awaken international consciousness and raise the resources needed to increase engagement and trust within the DRC and across its borders.